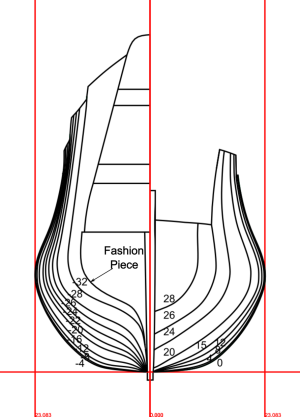

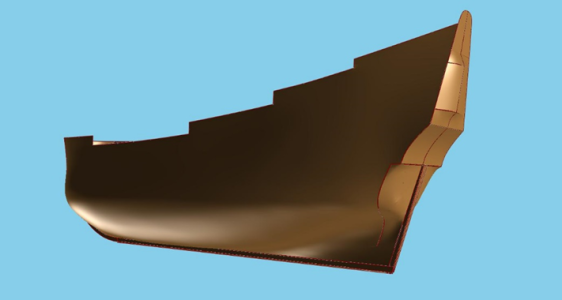

The Body Plan

The body plan shows the bends’ shapes. The bends are symmetrical, so once half a bend is drawn, the appearance of the other half is also known. Therefore, only half of each bend is shown on the body plan. The halves representing the bends fore of the midship bend are shown on the right half of the plan, and the halves depicting the bends aft of the midship bend are shown on the left half of the plan.Shipwrights drew their bends by following an established procedure. This consisted of progressively shrinking the bends as they moved further away from the midship bend. The rising lines told shipwrights where to shrink them (the bends were shrunk at the floor, breadth, and toptimbers), and the narrowing lines told shipwrights how much to shrink them. Consider the upper rising line at the 20th aft bend as an example. The versed sine for this bend (see the section on the aft upper rising line for further discussion) is 0.57 feet, and the narrowing is 1.38 feet. This tells us that the ship’s breadth here is 0.57 feet higher than it is at the midship bend, and its half breadth is 1.38 feet narrower than at the midship bend. Similar subtractions were performed for each rising and narrowing line at each bend drawn on the body plan, and the results were tabled. As the Treatise’s author explains; “The first thing to be done is to calculate and set down in a table the rising

and narrowings of all the bends that they may be in areadiness … The table being made, you may make every other bend out of the midship bend.” This explanation encapsulates the idea of whole molding that was discussed in the introductory material I presented; all bends are simply a modification of the midship bend.

After tabling the appropriate risings and narrowings, shipwrights plotted the relevant heights and widths of the floor, breadth, and toptimbers. This gave them three reference points through which they should draw a bend’s sweeps. In the present case, the radii of the sweeps are those given by Phineas Pett.

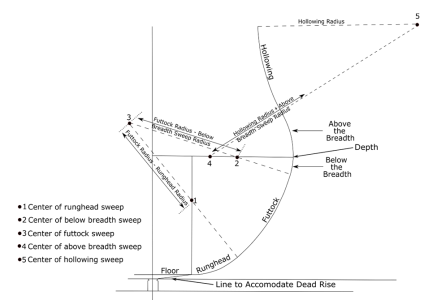

The next task was to find each sweep’s center and boundaries. When this was finished, shipwrights then used a compass to draw each sweep. Describing the procedure is simplest if we refer to Figure 80, and focus on how to find the futtock sweep’s center and its boundaries.[1]

The futtock sweep’s boundaries are found by first marking the radius of the sweep of the runghead along a line that runs up from the floor’s lateral boundary (this mark is point 1 in Figure 80.) A compass is then set to the futtock sweep’s radius minus the radius of the sweep of the runghead, and point 1 is used as a center around which a small arc drawn near point 3 in Figure 80.

Shipwrights then marked the radius of the sweep below the breadth along a line that ran horizontally along the bends’s depth and from its widest point (this mark is at point 2 in Figure 80.). The compass is set to the radius of the futtock sweep minus the radius of the sweep below the breadth, and another small arc drawn near point 3 in Figure 80. The point at which this arc intersects with the arc drawn as described in the previous paragraph is the center of the futtock sweep. The boundaries of the futtock sweep are obtained by drawing straight lines from its center, and through points 1 and 2.

Having found the futtock sweep’s boundaries, shipwrights now set the compass to the radius of the sweep of the runghead, place one of its legs at this sweeps center (point 1 in the figure), and drew the sweep from the floor up to the futtock sweep’s lower boundary. The compass was then adjusted to the radius of the sweep below the breadth, and this sweep drawn down to the futtock sweep’s upper boundary using point 2 as its center. Finally, the compass was set to the futtock sweep’s radius, and the sweep drawn from its upper to its lower boundary using point 3 as the center. If all goes well, the sweep reconciles (i.e., meets) with the other two sweeps.

Figure 80. Drawing a Bend

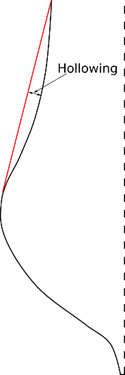

Note: The toptimber rising line typically does not fall at the bend’s top as shown in Figure 79. Rather, the sweep’s center, which is given by the intersection of two arcs whose radii equal the hollowing sweep’s radius and the sum of this radius plus the radius of the sweep above the breadth, is measured at each bend from a point given by the toptimber rising and narrowing lines.

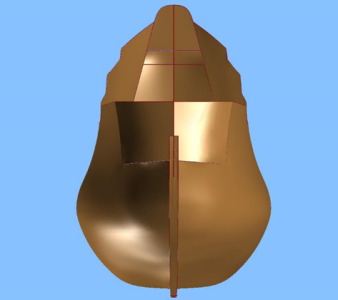

Shipwrights also allotted space for deadrise at the bottoms of their bends. This could be accomplished at and near the midship bend by drawing a straight line from the floor’s lateral boundary to the keel’s top (see80). This became unsatisfactory as the bends approached the bow and, particularly the stern. Here, a reverse curve was often drawn. The Treatise makes the radius of this curve equal to the radius of the runghead. This reverse curve gives the bends of 17th century ships their characteristic V-shaped bottoms.

It is worth noting that the procedure outline above, which is the procedure described by the Treatise, contrasts with John McKay’s description of it. He states that the center of the futtock sweep “is not located by horizontal and vertical measurements. By trial and error, one must find it ….” and that he also found the center of the toptimber sweep “by trial and error.” (9 p. 26)

[1] Notice that some sophisticated analytical geometry underlies how the centers of the sweeps are found. This attests to the mathematical prowess of early 17th century shipwrights.

My only regret is not having you as a source for information when I was forming the hull of my model 4 years ago. Even so, your treatise has been incredibly informative, and all of us who love the Sovereign are in your debt.

My only regret is not having you as a source for information when I was forming the hull of my model 4 years ago. Even so, your treatise has been incredibly informative, and all of us who love the Sovereign are in your debt.