Looking back for ships registered as Bluenose before 1921 the following list has been copied and pasted which does not advance your YQ models but adds to the brain bucket hold contents:

Library Catalogue

Top of Form

Bottom of Form

Nova Scotia Archives

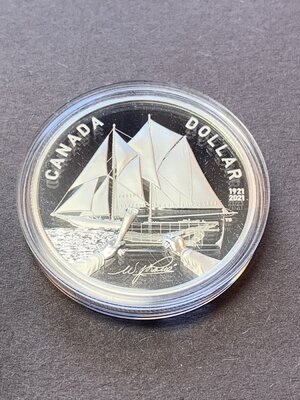

Bluenose: A Canadian Icon

Vessels Registered Under the Name: Bluenose - Prior to 1921

Bluenose — Brig — 159 Tons

Built in 1839 at St. Stephen, NB, by Messrs. Todd & McAllister

Registered: St. Andrews, NB, #7/1839

Owners: William Todd Jr. and John McAllister

Registered St. Andrews, NB, #14/1848

Owner: William Lancaster

Registered Liverpool, England, #353/1850

Owned by Thomas Miller MacKay and William Cowley Miller

Registered London, England, #493/1853

Bluenose — Schooner — 56 Tons — Official Number: 35,741

Built in 1850 at Mahone Bay, NS, by Elkanah Zwicker

Registered Lunenburg, NS, #18/1850

Owners: Casper Eisenhaur and Peter Eisenhaur

Registered Halifax, NS, #16/1851

Owner: James Murphy

Registered Halifax, NS, #14/1853

Owner: Joseph Mason and John McGrath

Registered Halifax, NS, #61/1854

Owners: Peter Martin Jr., George Martin Jr., William Martin and George Martin Sr.

Registered Yarmouth, NS, #5/1863

Owners: Robert Lonergan and John Lonergan

Sold foreign in 1865 at St. Pierre & Miquelon

Bluenose — Brig — 263 Tons — Official Number: 38,136

Built in 1860 at Weymouth, NS

Registered Yarmouth, NS, #40/1860

Owners: Samuel and John Killam

Sold foreign in 1868 at Amsterdam

Bluenose — Barque — 568 Tons — Official Number: 53,579

Built in 1865 at Truro, NS, by John Sanderson & Son

Registered Halifax, NS, #91/1865

Owners: John Dickie, Samuel Rettie, John Yuill, John Sanderson, Arthur Cochran et al.

Lost at sea in 1871

Bluenose — Schooner — 10.84 Tons — Official Number: 100,909

Built in 1889 at Caraquet, NB, by Joseph Sewell

Registered Chatham, NB, #31/1893

Owner: Joseph Sewell

Broken up. Registration closed 1920

Bluenose — Sloop — 2.40 Tons — Official Number: 107,073

Built in 1891 at Saint John, NB, by Frederick E. Sayer

Registered Saint John, NB, #9/1898

Owner: George Holder

Broken up at Marble Cove, 1919

Bluenose — Schooner 3 Masts — 166 Tons — Official Number: 112,062

Built in 1903 at Falmouth, NS, by Thomas W. McKinley

Registered Windsor, NS, #3/1903

Owner: --

Registered Bridgetown, Barbados 1916

November 14, 1919: Foundered off Peniche, Spain with a cargo of dried fish.

Bluenose — Schooner — 99 Tons — Official Number: 150,404

Built in 1921 at Lunenburg, NS, by Smith & Rhuland

Registered Lunenburg, NS, #8/1921

Owner: Bluenose Schooner Co., Ltd.

Registered Lunenburg, NS, #11/1936 on installation of an engine: 78.59 Tons

Owner: Bluenose Schooner Co. Ltd.

August 16, 1941: sold to Angus Walters

September 5, 1941: Walters sold 33 shares to 13 different people

June 27, 1942: Walters became sole owner

July 2, 1942: Walters sold the vessel to the West Indies Trading Co.

July 2, 1942: Mortgage of $16,000 to Angus Walters

Mortgage discharged November 2, 1842

Register closed 19 December, 1944 on sale to US Citizens

Amendment Jan 26, 1945 states the vessel under Honduras Flag

Lost off Haiti Jan. 29, 1946

Information taken from research material compiled by Charles A. Armour, 2003.

Rich