I have a project I started back in early 1999. I'll place this "build log" for it here, but first we need to go back in time and get caught up...

I've built working model boats of all sorts, but most being smallish tended to bob like corks in Baltimore's Inner Harbor where I sailed them. I wanted to build something large that would sail like a boat. I was inspired to action by a model of the Rattlesnake I saw in back-issue of Model Ship Builder magazine, but wasn't sure what boat to build.

The hermaphrodite, or "jackass" bark was a favorite rig of mine...

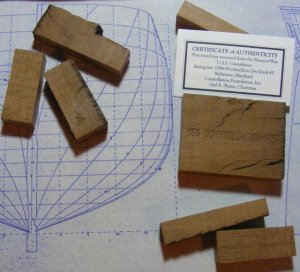

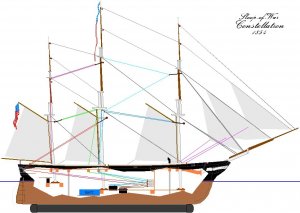

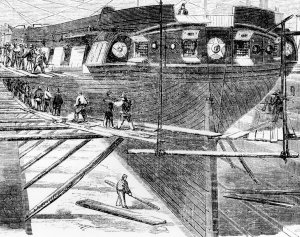

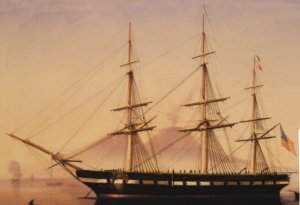

But a friend suggested a local boat that had just gone into dry-dock for restoration; the sloop of war Constellation, which the more I thought about it, the more it sounded like a good idea.

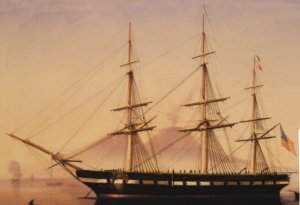

Constellation at Naples 1856 by Tomasa deSimone

Constellation at Naples 1856 by Tomasa deSimone

I won't get into the "controversy" surrounding this boat besides saying, this vessel is not and never was a frigate by any measure. The only people that buy that story also think the world is flat. A quick summary of her history can be found Here

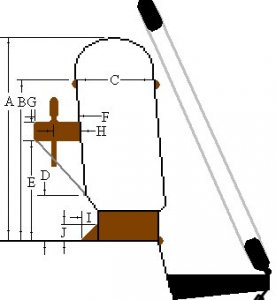

I made a visit to the National Archives in College Park Maryland and came home with her lines in 1:36 scale, her 1854 sail plan, and several other drawings of the ship, even the lines for her boats. Several drawings in their catalog were missing, such as her 1854 spar deck plan.

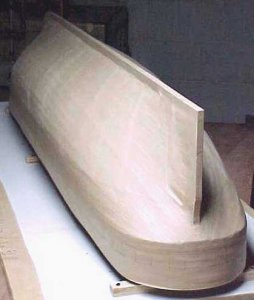

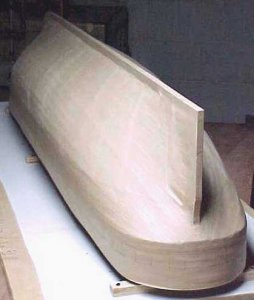

Rattlesnake was built with extended forms on a baseboard, something like Harold Hahn's method, and that's how I went about building Constellation. The forms were cut from thin plywood paneling pulled out of my house when I remodeled it, mounted on a particle-board base, also scrap from the remodel. The keel is 1/2" birch plywood.

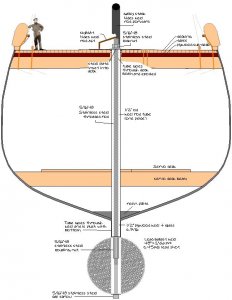

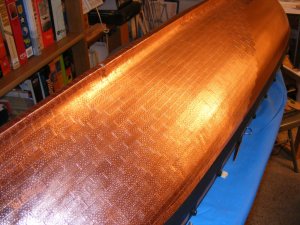

Before I started planking I came across a book by William Mowell about building the iron frigate Warrior. He battened the forms instead of planking and covered the hull in layers of brown paper packing tape, which he covered in masking tape, made a fiberglass mold from that, and laid up a fiberglass hull in that mold, the original "plug" being destroyed. This seemed like a great idea and a mold would allow me to easily make more than one hull, in fact, I decided to make three; one as the RC model, and two unrigged static models; one to be donated and the other sold, figuring a local Baltimore company would like a 5 foot hull of the Constellation in their lobby, and the money would pay for the whole project.

So off on this tangent I went...

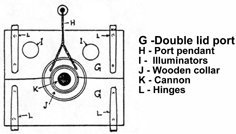

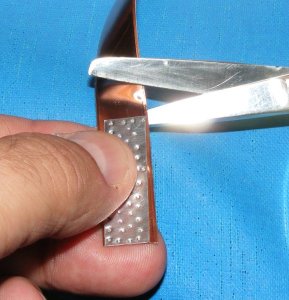

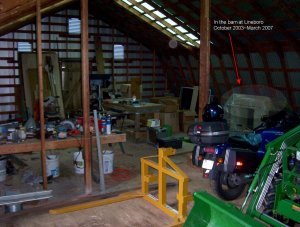

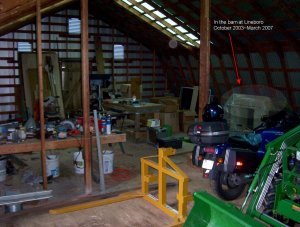

The idea was to lay on planking and other details on the "plug" to impart things like plank lines and moldings to the mold, but there were a lot of such details not shown on anything I found at the archives, so I had more research to do. In the mean time we moved to a small farm and the plug was stored under plastic in the corner of the barn.

The wife and I split up, we sold the farm and the plug went into a storage unit. I bought a house with a workshop in a separate building and in 2009 pulled the old plug out to resume work on it, a decade later.

Next up: How NOT to build a hull

I've built working model boats of all sorts, but most being smallish tended to bob like corks in Baltimore's Inner Harbor where I sailed them. I wanted to build something large that would sail like a boat. I was inspired to action by a model of the Rattlesnake I saw in back-issue of Model Ship Builder magazine, but wasn't sure what boat to build.

The hermaphrodite, or "jackass" bark was a favorite rig of mine...

But a friend suggested a local boat that had just gone into dry-dock for restoration; the sloop of war Constellation, which the more I thought about it, the more it sounded like a good idea.

Constellation at Naples 1856 by Tomasa deSimone

Constellation at Naples 1856 by Tomasa deSimoneI won't get into the "controversy" surrounding this boat besides saying, this vessel is not and never was a frigate by any measure. The only people that buy that story also think the world is flat. A quick summary of her history can be found Here

I made a visit to the National Archives in College Park Maryland and came home with her lines in 1:36 scale, her 1854 sail plan, and several other drawings of the ship, even the lines for her boats. Several drawings in their catalog were missing, such as her 1854 spar deck plan.

Rattlesnake was built with extended forms on a baseboard, something like Harold Hahn's method, and that's how I went about building Constellation. The forms were cut from thin plywood paneling pulled out of my house when I remodeled it, mounted on a particle-board base, also scrap from the remodel. The keel is 1/2" birch plywood.

Before I started planking I came across a book by William Mowell about building the iron frigate Warrior. He battened the forms instead of planking and covered the hull in layers of brown paper packing tape, which he covered in masking tape, made a fiberglass mold from that, and laid up a fiberglass hull in that mold, the original "plug" being destroyed. This seemed like a great idea and a mold would allow me to easily make more than one hull, in fact, I decided to make three; one as the RC model, and two unrigged static models; one to be donated and the other sold, figuring a local Baltimore company would like a 5 foot hull of the Constellation in their lobby, and the money would pay for the whole project.

So off on this tangent I went...

The idea was to lay on planking and other details on the "plug" to impart things like plank lines and moldings to the mold, but there were a lot of such details not shown on anything I found at the archives, so I had more research to do. In the mean time we moved to a small farm and the plug was stored under plastic in the corner of the barn.

The wife and I split up, we sold the farm and the plug went into a storage unit. I bought a house with a workshop in a separate building and in 2009 pulled the old plug out to resume work on it, a decade later.

Next up: How NOT to build a hull

Last edited: