Dear Friends

RESEARCH RESULTS - PART 3: THE THIRD AND FINAL EXPEDITION TO THE NORTH 1596

First off, I have suspected the outcome of this final piece of research for more than 6 months. I have been in two minds since then whether or not to post my findings. However, after a further 6 months of continuous research all further collected evidence reaffirmed my conclusion. In addition, it simply wouldn't be fair to all of my friends who have supported me so wonderfully and loyally in this build, if I did not share my rationale with them.

So, what do we know about the third expedition that is factual? Please note that I am only referring to information that pertains to the two ships used on the Third Voyage.

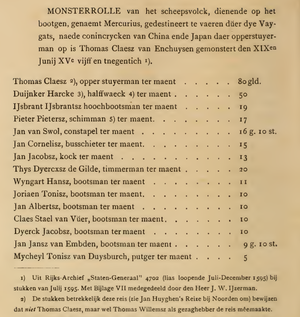

Today I will start proceedings by first referring to the Hakluyt Society's English translation with comments by Dr. Beke as this source - surprisingly - is the one that offers us the least information on the ships of the Third Expedition.

View attachment 353588

De Veer's original journal does not contain much more information except that it does list the tonnage (last) of the two ships.

View attachment 353587

So, what can we conclude from the above two sources? (Precious little, I am afraid).

1.

There were two ships that took part in the third and final expedition.

2.

The one ship was of 50-60 last and the other one of 30 last.

We also have to bear in mind that we do not have the benefit of a Jan Huygen van Linschoten version of the Third Expedition as he did not partake in it. And this my dear friends, conclude the factual information that we have of the ships of the Third Expedition - that's it!

Those are the facts – now we come to the interpretations and subsequent hypotheses if we want to get closer to the truth.

I can think of no two more authoritative interpretations than those of Ab Hoving and Gerald de Weerdt so let's run with those first.

Ab Hoving

In his book Ab Hoving writes: "From De Veer’s diary we know that Barentsz’s expedition consisted of two ships, one of 30 last and one of 50 last. This was the same scenario as with Abel Tasman’s expedition where one ship consisted of 60 last (the jacht Heemskerk) and the other of 100 last (the fluyt Zeehaen). Common sense would have one assume that the most prominent person/people on the expedition will sail on the ship with the biggest lasten. However, during Tasman’s expedition this was not the case."

Hoving mentions that the Heemskerk was in fact 6 feet longer than the Fluyt and equipped more economically, which, in turn, made the ship more maneuverable and better sailing. Analogous to this, he draws the conclusion that Barentsz and Heemskerk would have been on the smaller of the two ships, i.e., the one of 30 last.

Gerald de Weerdt

De Weerdt comes to the same conclusion. He states that when he and his team’s had to decide on which ship to reconstruct, their choice fell on the ship of Barentsz. He reckoned that the size of the crew (15 men excluding Barentsz and Van Heemskerk) was indicative of them being on the smaller ship of the two ships, i.e., the one of 30 last.

So, in summary, even though Hoving and De Weerdt cite different motivations, they both reached the same conclusion – Barentsz’s ship was the one of 30 last.

Unfortunately, I disagree with both these assumptions: Let me first comment on De Weerdt's reasoning:

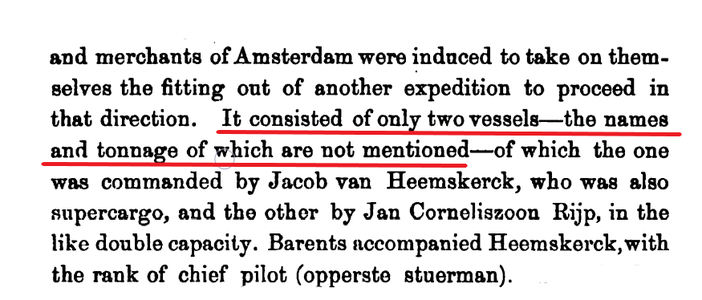

De Weerdt surmises that a crew of 15 (excluding Barentsz and Van Heemskerk) point to a 30 last ship. Well, during the 1595 expedition, the 50-last Mercurius from Enkhuyzen sailed with only 15 men including the captain.

View attachment 353598

This shows the "monsterrol" crew register of the 50 last Mercurius of Enkhuizen during the 1595 expedition. This is so detailed that it even shows the salary received by each of the 15 men. The footnote also points to an error in that the captain was in actual fact Thomas Willemsz and not Thomas Cleasz. (Also see my report of yesterday).

The above clearly points to De Weerdt's theory being nothing more than a theory -

this does NOT prove that Barentsz's ship was the one of 30 last.

Next, I will comment on Ab Hoving's reasoning and why I disagree with that:

As his example, he chose the Abel Tasman Expedition - an expedition which …

(a) Was to a totally different part of the world (the Southern Seas).

(b) Was not a polar expedition

(c) Featured two distinctly different types of ships with very different design parameters and sailing characteristics (a Jacht and a Fluyt).

(d) Featured different protagonists to Barentsz and Van Heemskerk and

(e) Took place 46 years after Barentsz's Third Expedition during a time when Dutch shipbuilding was already in a process of reformation).

I can understand his reasoning in choosing the Tasman expedition if we did not have any other example to go on, but we do!

Why did he not use the data of Barentsz's Second Polar Expedition in 1595 which ...

(a) Was identical to the third - both as far as its geographical location and objectives were concerned?

(b) Featured essentially the same types of ships (albeit with varying sizes and tonnages)?

(c) Featured the same two protagonists in Barentsz and Van Heemskerk?

(d) Happened only one year earlier and was therefore far more relevant?

(e) Offered us an invaluable opportunity of gaining knowledge of the strategy employed by the three different Admiralties (Zeeland, Enkhuyzen and Amsterdam)?

I have purposely left out Rotterdam because they contributed only a single jacht of 20 last and therefore there was no choice of ship available to them. In contrast to Rotterdam, all three other Admiralties employed both larger and smaller ships offering their prominent crew members a choice of which to use.

And what did these statistics show?

Exactly the opposite to Hoving’s findings based on the Tasman Expedition! In all of those cases the prominent men were on the ships with the bigger lasten (De Griffioen in Zeeland's case, De Hoope in Enkhuizen's case and De Windhond in Amsterdam's case). This paints a completely different picture to the one that that Barentsz was on the smaller ship.

In fact, this would point to Barentsz and Van Heemskerck being on the larger of the two ships.

This is why I placed such a big emphasis on the ships' number of lasten (tonnage). I am 100% in agreement with both Hoving and De Weerdt in that the size would have played a crucial role in determining the identity of Barentsz's ship, but unlike De Weerdt and Hoving who believe that Barentsz was on the 30 last ship, I believe that he could just as well have been on the 50 last ship - a ship that Amsterdam had in their possession - a ship which had served them very well during both the 1594 and 1595 expeditions - a ship on which Barentsz himself was captain in 1594 - a ship of 50 last called

De Mercurius.

And the best is that I am not alone in my finding. That is why the Russian National

Agency -VESTI- reports as follows:

View attachment 353600

The reference to "caravel" is due to incorrect translation - it actually refers to "ship".

As does the Independent Arctic Research and Information Agency, Barents Observer.

View attachment 353601

As does the Russian Information Center and

View attachment 353605

and Science and Life Magazine

View attachment 353604

Unique artifacts transferred to the Arkhangelsk Regional Museum of Local Lore

On the very last day of work, the expeditioners found four fragments of frames of the bottom part of Willem Barents' ship.

View attachment 353606

On October 21, Dmitry Kravchenko's search expedition on the Ship Aldan returned to Arkhangelsk. Recall that the expedition, which included underwater archaeologists, divers and hydroacoustics, geophysicist and employees of the Russian Arctic Park, spent a month on the territory of the Russian Arctic National Park in the Ice Harbor Bay, near Cape Sporey Navolok. The purpose of the expedition was to confirm with the help of special instruments the presence of a natural geomagnetic anomaly a few meters from the shore, and to convince the scientific community that this anomaly is nothing more than the skeleton of the

Mercury of the Dutch skipper Willem Barents. Underwater archaeologist, historian, Dmitry Kravchenko has been looking for the famous Dutch shipl for several decades. In 2012, the expeditions provided financial assistance to the Russian Geographical Society and the Foundation for assistance to the northern and Arctic territories "The North is ours!".

Dmitry Kravchenko: "The expedition faced an insurmountable factor playing against us – the elements. Snow drifts, wind up to 30 m / s, surge waves near the shore, negative temperatures could not allow us to fully realize our plans. For example, due to the strong wave, it became more difficult to work with the magnetometer and side-scan sonar, which failed and gave erroneous readings. Of the 11 studies planned, we were not able to use the full five days. However, luck still smiled on us: almost on the last day of work, we found 4 fragments of frames at the water's edge. And most importantly - they belonged to the bottom of the ship! Now the saws have been removed from each of them that will be studied using radiocarbon analysis at the Geological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences."

The fact that the wooden fragments belong to the Dutch vessel, Dmitry Kravchenko himself does not doubt for a second. His arguments in favor of the theory of Dutch origin - the composition of the material of the artifacts found - is clearly a deciduous tree, more likely an oak. The Pomors did not build their kochi and karbas from oak, it simply did not exist in the north. In addition, the method of fixing the nails and the nails themselves, according to Kravchenko, also testify to the Dutch trace.

Now the finds have been transferred to the Arkhangelsk Regional Museum of Local Lore. The Kravchenko expedition transferred more than two thousand fragments of artifacts (weapons, tools, dishes, fabric, shoes, ceramics) belonging to the Dutch expedition of 1596-97 in the museum's funds. The historian's dream is to reconstruct Barents’ ship. The main conclusion that the expedition made after working in the Ice Harbor is that the vessel should not be found in the place where it was previously assumed.

"We found fragments of frames - these are the first finds of the bottom of the vessel. They have negative buoyancy and can only be in close proximity to the bottom. It turns out that we now know where the remains of the caravel lie approximately at the bottom. Previously, we relied only on instrument readings, but now we will search based on recent observations."

Next year, the expedition will start earlier in time, its goal will be to detect the remains of the ship, determine the condition of the keel part of the vessel, and work out the method of erosion. Whether or not to raise the ship in the event of its detection is still an open question. The director of the park "Russian Arctic" Roman Ershov suggested not to rush into this sensitive issue and so far to conduct only photo and video shooting to document the presence of a vessel at the bottom. "We do not know how the material, which has been lying at the bottom for several centuries in a row, will behave," Roman Ershov explained his position. He thanked the participants of the expedition for their work in the park and the finds provided to the museum.

AND THAT IS ALL FOLKS!

Agency -VESTI- reports as follows:

Agency -VESTI- reports as follows: