They essentially did the same thing with the Vasa kit. The artwork is of the 1:10 model at the Vasameet...This will be a fascinating project. I am somewhat amazed that DeAgostini markets the kit with pictures of an entirely scratch-built model; that hardly seems fair, or honest. Nevertheless, Roller’s log in the German forum shows to quite an amazing degree what can be done with this kit.

I wish you luck, and I will gladly follow along.

-

Win a Free Custom Engraved Brass Coin!!!

As a way to introduce our brass coins to the community, we will raffle off a free coin during the month of August. Follow link ABOVE for instructions for entering.

-

PRE-ORDER SHIPS IN SCALE TODAY!

The beloved Ships in Scale Magazine is back and charting a new course for 2026!

Discover new skills, new techniques, and new inspirations in every issue.

NOTE THAT OUR FIRST ISSUE WILL BE JAN/FEB 2026

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

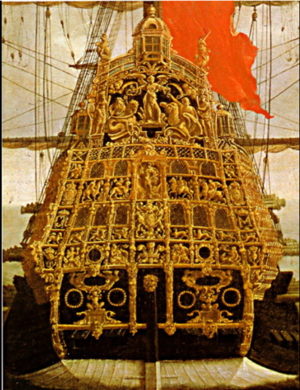

HMS Sovereign of the Seas - Bashing DeAgostini Beyond Believable Boundaries

- Thread starter DARIVS ARCHITECTVS

- Start date

- Watchers 105

Kurt, will you be using the supplied bamboo strips?

I pre-purchased the book while it was still being written. The pictures above are from the book.Kurt, I didn't see that anyone had mentioned it, but I just purchased 'Sovereign of the Seas 1637' by John McKay from USNI. I'm using it as a reference for my HMS Prince project, but thought you might find it extremely useful in your construction journey. It has pretty much every detail of the 1637 version of the ship you would need to assist in your construction. All the best, Matt

Matt, belay my reply. I just read your belay message!Kurt, belay my last...just noted a McKay reference in an early entry. Good luck with the build. All the best, Matt

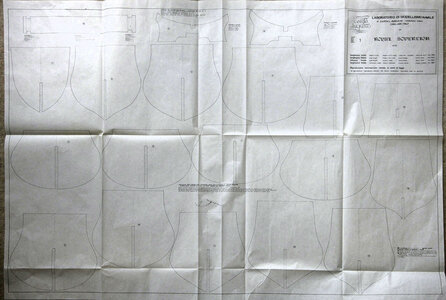

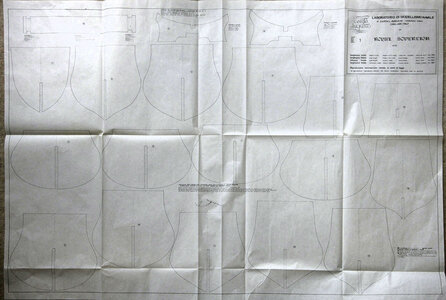

Many thanks Ken! Those frames will definitely influence how I reshape the DeAgostini frames, or how much I do not need to shape them. I just finished tracing the McKay patterns onto the wooden parts of the DeAgostini model. Quite a difference. The DeAgostini form is more round and full, similar to the Corel La Couronne. The McKay form strongly shows the sharp curves of the radii at the turn of the bilge and at the side at the wales, combined with a flatter bottom than your Royal Sovereign frames above.Hi Kurt, This ship is my next project after I finish my Amerigo Vespucci, probably just after Xmas. It is a kit from about 1970, CARTA AUGUSTA, more of a scratch build unlike modern kits. I can see that the plans differ from most other offerings but I thought that you just might find something helpful in them, you can’t have too many sources

Sorry about the quality of the photos but the light indoors at the moment is very poor and the drawings are very fine lined.

Ken

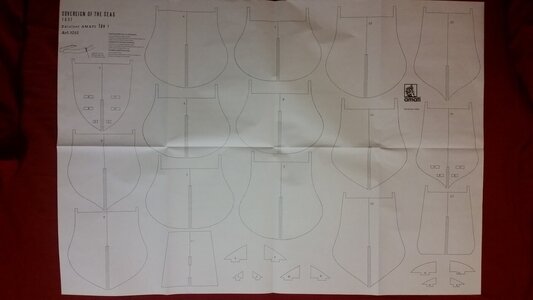

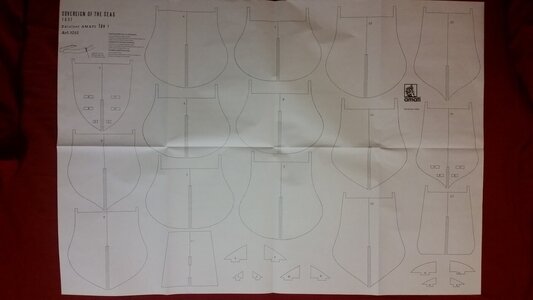

View attachment 194294

View attachment 194295

View attachment 194296

View attachment 194297

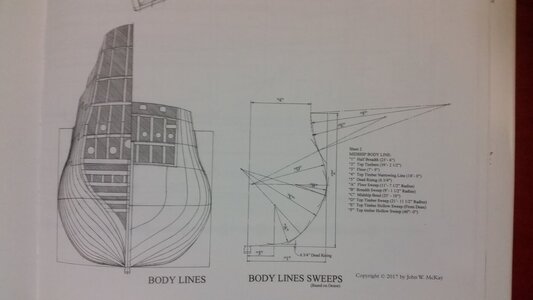

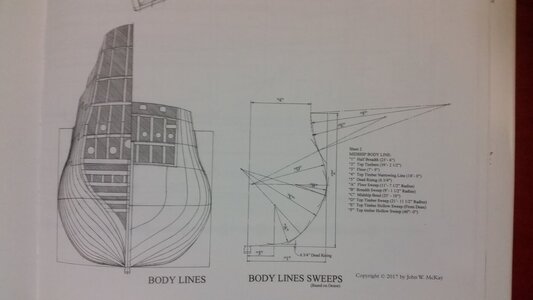

Wow, that's a lot to take in. You could make a career out of studying the sweeps and hollows that make up the body form. For my purposes, an approximate is good enough, with care taken to accurize the kit parts within reason. It's not like I'm to test the hydrodynamic behavior of this ship in a wave tank.I wouldn't worry too much about McKay. You might have a look at the reviews of this book on Amazon, and particularly the review by Frank Fox, who is the preeminent naval historian on ships of this era. I would add to those comments that the McKay's idea of starting with Deane wasn't a very good one.

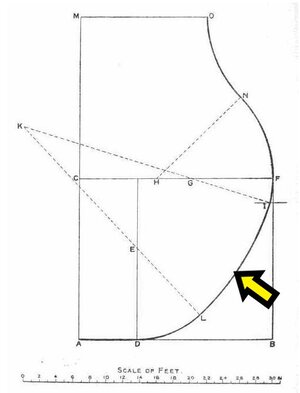

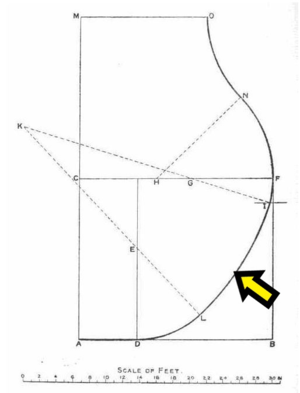

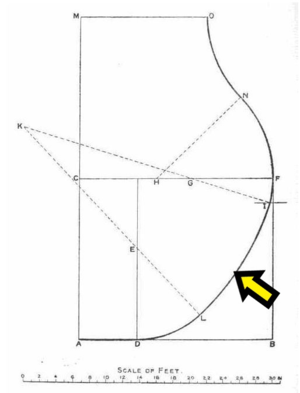

We can compare the width of the floor and the dimensions of the sweeps given by Phineas Pett, the ship's designer (Pett's sweeps are given in an article in a 1919 issue of The Mariner's Mirror by R.C. Anderson), to the floor and sweeps we can compute from Deane, and from the Treatise on Shipbuilding (ca. 1620-1625). As you can see in the attached photo, the Treatise is closer to Pett's sweeps than is Deane.

Notice that the photo shows a midship bend with four sweeps. You can make the argument that it really had five sweeps. The sweep omitted by Pett is the hollowing sweep. The length of this sweep is given in a letter written to King Charles by Pennington in 1635, and are reproduced in the Autobiography of Phineas Pett, which you can find for free on line. I should add that the opinion of WG Perrin (the editor of Pett's autobiography) is that Pennington's plans were used instead of Pett's. That's not right, but it would take a lot of pixels to explain why.

Also, please remember that the attachment is a photo. I don't have the gear to properly shoot pictures of plans, so there is some distortion in the width at the top. Nevertheless, you get the idea.

The plans from about 1800 are also problematic. They don't show any dead rising, which the Sovereign almost certainly had. Pett build the Royal Prince without it, and was so roundly criticized by shipwrights, that it was a mistake he wouldn't repeat. If Werner's plans are the ones I'm thinking of, they also have this problem (for that matter, so does the photo I attached, so view it as more of a cartoon than an actual plan).

The bottom line here is that you pretty much have to draw your own plans to get it right (or, at least close to right). This is a MAJOR undertaking that involves hundreds of little decisions that never seem to make it into books. It's taken me about 2,000 hours just to come up with a reasonable sheer plan, but but it's so messy that I'd be embarrassed to show it to anyone, and I still have the body plan to do.

Not trying to be a killjoy here. Have fun with the model. That's what really counts.View attachment 194313

The key questions that come up are, how strong were the hollowing curves adjacent to the keel, how flat was the bottom (what was the approximate angle of incidence of the bottom near the keel), and how sharp were the curves at the turn of the bilge? Which set of information looks the closest to the Pett design between DeAgostini, John McKay, your Royal Sovereign model and the Amato plans which I have? Looking for the simplest answer. Basically, I have to choose one, and slightly modify the DeAgostini frames to match at close as is practical. Please do not shy away from expressing your opinion. No penalty if the ship end up looking fake like the Black Pearl, that's on me.

The key questions that come up are, how strong were the hollowing curves adjacent to the keel, how flat was the bottom (what was the approximate angle of incidence of the bottom near the keel), and how sharp were the curves at the turn of the bilge? Which set of information looks the closest to the Pett design between DeAgostini, John McKay, your Royal Sovereign model and the Amato plans which I have? Looking for the simplest answer. Basically, I have to choose one, and slightly modify the DeAgostini frames to match at close as is practical. Please do not shy away from expressing your opinion. No penalty if the ship end up looking fake like the Black Pearl, that's on me.Yeah, that move of marketing the Italian scratch built kit with a simplified copy using cheap materials and shortcuts was BS. But, a bit of bashing can return it to it's former glory. Roland Röler made huge changes and additions. I think I can make most of the same changes, including the deck support structures, and add to that a full lower gun deck. A lot of wood bending will be required to get the deck camber.This will be a fascinating project. I am somewhat amazed that DeAgostini markets the kit with pictures of an entirely scratch-built model; that hardly seems fair, or honest. Nevertheless, Roller’s log in the German forum shows to quite an amazing degree what can be done with this kit.

I wish you luck, and I will gladly follow along.

Hell no. The bamboo has rounded edges, and although soft enough to bend, the hardness is not even, so you get sharp and shallow curves and you bend the wood over the frames. It's being scrapped out. I'm using basswood I bought off eBay (Here's a link: Basswood Strips from Midwest Products). I don't know the quality of that wood with regard to bending, but we'll see. If it is too dry and prone to splintering, I'll purchase some quality lime strips from a model timber supplier.Kurt, will you be using the supplied bamboo strips?

Here's what I have for resources with regard to frames. Which would you guys choose? Would you change the profile of the DeAgostini frames? If so, how? There is a drastic change between DeAgostini and McKay as you can see. Perhaps more hollow curve near the keel, or more flatness between the turn of the bilge and the side? Less of a flat bottom at midship (more angular)?

DeAgostini (McKay frame Lines penciled on one side for comparison):

Amati:

Royal Sovereign by Carla Augusto:

John McKay (based on Deane):

DeAgostini (McKay frame Lines penciled on one side for comparison):

Amati:

Royal Sovereign by Carla Augusto:

John McKay (based on Deane):

Very interesting topic, looking at the Pett, treatise and Dean lines there is not a major difference in these. From here to me it looks safe to go with mc kay s Deans based lines because he already did all the work for a full body.

Then the next topic would be to alter mc kays flat tuck into a round tuck which will properly fit into his lines plan.

Then the next topic would be to alter mc kays flat tuck into a round tuck which will properly fit into his lines plan.

CharleyT was right in his previous post. On further consideration of the reviews of John McKay's book by Frank L. Fox and Charles Aldritch, I find it hard to trust ANY of the conclusions that John McKay made regarding the construction of SoTS. The amounts of errors I counted among the reviewers, plus what I know as a Marine Engineer myself, have eroded my confidence in the author greatly. I have seen one other author write a book that became touted as the definitive book on the subject, found in every major library in the world, yet was so inaccurate that any who followed it would be seriously misled making reproductions from it. That book is The Crossbow by Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey in 1903. It pains me that John McKay's book will likely become similarly popular and most people seeking to learn about HMS Sovereign of the Seas will not see past the pretty pictures and drawings to learn how many historical sources he ignored, as well as advise from current experts, and how he misinterpreted those sources he did utilize. I encourage those who have purchased McKay's book to likewise read the book reviews on Amazon. Their arguments are well founded. Gather as much information from other sources as you can. After reading McKay myself, I found myself asking why he insists that the hull shape was so fine, because he doesn't back up his opinion with information on that point. For me, the doubts all started with that ridiculous stern and the unnecessary "officer's companion way" located immediately adjacent to another companion way, both leading from the weather deck down to the upper deck. Why would you need TWO ladders in the place? As an ship's officer myself, I would think my fellow officers were never elitist enough to not suffer treading the same ladder as the crew. I'm now thinking that the only changes I should make to the DeAgostini frames would be to sand some flatter spots between the turn of the bilge and side of the hull as shown below.Very interesting topic, looking at the Pett, treatise and Dean lines there is not a major difference in these. From here to me it looks safe to go with mc kay s Deans based lines because he already did all the work for a full body.

Then the next topic would be to alter mc kays flat tuck into a round tuck which will properly fit into his lines plan.

Elaborating on my previous post, copies of the comments on John McKay's book are provided here:

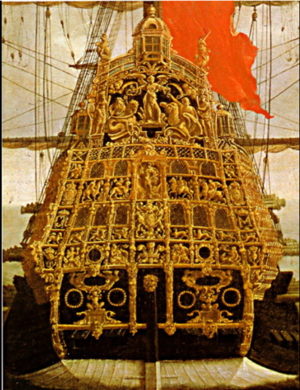

In the acknowledgements to his book, Sovereign of the Seas 1637, John McKay thanks me for advising him on the ship's design. What he does not say is that he rejected most of what I told him, did not ask me about many subjects on which I could have offered help, and I most definitely do not want readers to think that I endorse the results.

He commits a gross error in giving an English warship of 1637 a square-tuck stern. A round tuck was adopted by English shipwrights by at least 1616, with a period of transition earlier. By 1620-23, when Sir Henry Mainwaring compiled his Seaman's Dictionary, the stern timbers and planking near the waterline in English ships were already called "buttocks" because of their convex shape. There are about a dozen careful stern view drawings and paintings by marine artists, especially Willem van de Velde the Elder, of English ships built or rebuilt in or before 1637, and one draft. All show round tucks, none square. Mr. McKay goes so far as to claim that master shipwright Sir Anthony Deane shows square tucks in his designs around 1670. They in fact show nothing whatever of the shape of their sterns. Deane's large ships all had normal round tucks as shown by numerous drawings, paintings, and dockyard models. Mr. McKay's authority for the square stern is the portrait of shipwright Peter Pett (who built the Sovereign to his father Phineas's design) attributed to Sir Peter Lely. This shows conflicting evidence; it has the knuckles of a square stern, but the stern planking is curved as in a round tuck. In square-tuck ships, the planking is dead straight and diagonal. Mr. McKay ignores the carvings design superimposed on the above-water draft by Peter Pett in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which he reproduces. This clearly shows shading at the lower corner of the stern, proving a round tuck. Why would one accept the ambiguous evidence of a Dutch portrait painter with no marine art to his credit over that of the shipwright who built the vessel? There is in fact an anachronistic painting in the National Maritime Museum, London, by Jacob Knyff portraying the ship as she appeared in the 1650s (royal arms and insignia removed); it shows a round tuck.

This book not only shows a square stern, but a bizarre square stern in which the flat portion extends below the waterline almost to the keel. This would absolutely ensure a rough, turbulent flow of water to the rudder, which would thereby be rendered quite useless. The rudder itself has problems. Its head extends partly into a huge hole in the counter as in the 18th century, and the tiller enters the hull beneath the upper deck rather than beneath the middle deck as it should. There is no sign of a sweep for the tiller and no gooseneck. From the text, the author seems not to understand that the whipstaff slid THROUGH the rowle right to its end, which is why the helm could swing 20 degrees.

The next major mistake is the falls (abrupt step-downs) in the decks. These had been condemned by the Naval Reform Commission of 1618. The designer's dimensions list for the Sovereign unequivocally states, "All the decks flush fore and aft," and Peter Pett's draft at Boston shows them flush. Why would Mr. McKay ignore direct evidence from the designer and the builder? The author is swayed by a drawing by Van de Velde the Elder showing the middle deck ports under the quarter-gallery lower than the others. Though Mr. McKay supposes this was an early drawing, it was actually made in the mid-1670s, as shown by the little bridge therein which is first mentioned at that time as running to the landing stage at the ship's mooring off Gillingham. The drawing is a copy of the decorations and features in the famous Payne engraving, superimposed on the hull Van de Velde saw in the 1670s (it is actually a cut-out pasted in over his original). That it is copied from Payne is proven by both sharing the same curious mistake: the grating over the halfdeck extends only part way up the door in the quarterdeck bulkhead. People under the grating would have had to crawl around on hands and knees, or duck-walk. The explanation is that John Payne, as known from a documentary source, drew the ship in drydock well before her launching. The grating was undoubtedly still under construction, resting on sawhorses or some such, and had not yet been raised into position. The reason for the differing height of the middle deck gunports in the Van de Velde version is that in the ship's rebuilding in 1659-60, the decks had been re-laid about 18 inches higher at the side than in the original, and the draft increased by some three feet. With the quarter-gallery thereby becoming lower relative to the deck, gunports could no longer fit under them. Two Van de Velde drawings of the Sovereign in 1673 and a painting of 1678 formerly at Lowther Castle show that there were NO middle deck gunports under the gallery after 1660. For Van de Velde to show them there as in the Payne engraving, he had to place them lower than the other ports which had been raised.

The framing shown by Mr. McKay is nothing like that of a 17th-century ship. He shows huge gaps between floors and first futtocks. For what these should be like, I recommend Richard Endsor's new book, The Master Shipwright's Secrets. This shows that the floors and first futtocks were bolted together at the frame bend stations, timbers between laid in loose, and the density of framing almost solid in the lower parts of the hull, and drastically reduced in the upper portions. This Mr. McKay could have known even from the preserved framing of the Tudor ship Mary Rose.

There are many other errors. There are no chocks at the timber heads. The riders are of 18th-century form, extended upwards by complex scarfs which weren't used for these in the 17th century. Mr. McKay shows the main pumps as brake pumps, though large English ships used chain pumps by at least the early 1620s. He shows a triple crab capstan with holes for bars on all levels, whereas English three-deckers had two double jeer capstans operated only from the upper level, and no belowdecks spindle. The position deep in the hold shown for the cook-room is improbable. If not in the forecastle or on the second deck below the forecastle, it would have been on a platform laid on false beams beneath the gundeck under the waist. Mr. McKay seems not to realize that the term "orlop" before the mid-1660s meant the gundeck. Below the orlop/gundeck, big English ships before the 1660s had heavy "false beams" supporting a series of platforms which were not a continuous deck.

Then there are the guns. Mr. McKay misunderstands the Sovereign's "drake" guns. In these the whole bore was not tapered as he supposes, but just the chamber. It was designed for small charges, so that a thin-walled weapon could fire a large-caliber ball for the gun weight. Drakes had a very short range and a violent recoil. The cannon-of-seven fired a shot weighing 42 pounds, not 60 as he says, and was in use in the Royal Navy until the mid-1780s. He also shows four-truck gun carriages, while the carriages made for the Sovereign were all drake carriages with "whole trucks and half trucks;" that is, semi-circular skids at the rear end to slow the ferocious recoil. Also, a dedicated train tackle (he indicates two per gun) was not issued to British sea gunners until the second half of the 18th century.

Even the ship's history is incomplete. Mr McKay omits three great actions in which the Sovereign took a major part: Solebay and the two Schooneveld battles, in the last of which the Sovereign was the fleet flagship for the first time. It is also untrue that Robert Lee, who rebuilt the ship in 1684-85, said her original timbers had never been changed. He said the SHAPE of the original timbers had not been changed.

Overall, this book is characterized by draftsmanship of marvelous quality, and many may buy it for that reason alone. But Mr. McKay's research was doomed by a lack of understanding of the context of his sources, and of Early Stuart shipbuilding practices. Thus, any modellists who attempt to recreate the Sovereign of the Seas based on this book are going to get badly inaccurate results.

Frank L Fox

When I first found out that this book would be published I was really enthused about it and eager to purchase it. One look at the dust jacket on Amazon, however, immediately made me skeptical. I'll explain why shortly. In spite of my misgivings I ordered the book. I had owned some of the author's previous works and admired their quality. His drafting skill is world class and I assumed that there would be drawings that would make it worth the buy. There are many excellent drawings of the ship's carvings that I like. And, as usual, all the drawings are beautifully done. Having said that I'll now move on to the bad news.

The stern on his reconstruction is an absolute joke. I'm a ship model builder and I've been researching this ship for a long time. Throughout this research I've had the help of experts who are unquestioned authorities on the seventeenth century royal navy. I'll take opinions from people like that any day. They've devoted their lives to this and can access information that few people are even aware of. That includes the author of this book. I can assure you that my opinions about this ship are the same as theirs.

I'll deal with the square tuck McKay favors first. For those not familiar with the term it refers to the area immediately below the wing transom. This is also sometimes called the main transom. I've included a picture of an actual square tuck on a 4th rate ship of about 1691. Ships of this size and smaller sometimes had these tucks but larger ships never. You can clearly see the planking on the tuck. The author comes to his conclusion about the square tuck on the Sovereign on some rather flimsy evidence. There is a well known painting which includes a view of the stern of this ship. This picture is the only evidence of any kind that supposedly shows a square tuck. The problem is that it's impossible to tell what it really means. I've attached an enlargement of the picture so you can follow me. At first glance it does look as if it shows a square tuck. On further inspection, however, you'll notice that the planking on the tuck is curved. And the curves of the plank are angled exactly the way they would be for a round tuck. A square tuck would have straight planks just as they are on the 4th rate model. It's hard to say what's going on here. The artist may have been confused about what he was looking at. Who knows? What I do know is this. This painting is worthless as proof of anything because it seems to show two different things for the same area. Of course McKay has taken care of this little problem by simply making the planks straight on his reconstruction drawing taken from the painting. The evidence for a round tuck is pretty straightforward. The preliminary draft for the ship has this area shaded in a way which clearly means rounded. McKay seems to think that the round tuck was something unusual at the time when the Sovereign was built but there are several pictures of large ships built between 1623 and the year she was launched and they all have round tucks. From that period and to the end of the century there are no pictures and no models of large ships with anything but round tucks. None. That includes the Sovereign. It would appear that during that time the round tuck had become the standard for 3rd rate ships and above. It's hardly likely that they would have backslid and put an outmoded stern on a ship of this importance. Especially since it happened to be the king's pet project. And one more thing to finish this subject. Not only does McKay give the ship a square tuck but he continues the flat stern all the way down to the keel! Neither I nor anyone I've talked to about this has ever seen such a stern on any seventeenth century English ship. Possibly he could explain how a clean run of water would get to the rudder.

The second item I totally disagree with are the falls in the decks. I believe that he primarily bases his deck fall theory on the Van de Velde drawing that was done somewhere around 1661. The drawing is obviously based to a great extent on the Payne print which was done right after the launch of the ship. The two aftermost middle deck gun ports in this drawing are well below the others. The ship was launched in 1637 and had documented rebuilds in 1651 and 1659-1660. The deck heights were definitely altered in the last one. So the artist couldn't have ever actually seen it in its original form and that's what we're concerned with here. Obviously, the drawing cannot be considered a reliable source of information for the ship in its early form. This one drawing is the only indication of anything but flush decks in any visual representation of the ship. All other drawings starting from the original draft and going on to the last ones later in its career show flush decks. The preponderance of the evidence is definitely in favor of flush decks. And one more thing. The biggest English ship before the Sovereign was the Prince Royal which launched in 1610 and it also was designed by Phineas Pett. It did have deck falls but these were deemed unnecessary by a 1618 commission and the ship was given flush decks in a 1623 alteration.

And now we turn our attention once more to the stern painting that McKay has such great faith in. This rendition of the stern is far from perfect but I'm simply going to concentrate on one of them because I know it caused what I and the experts consider a massive blunder. In the painting the rudder head is shown as being above the middle deck chase ports. From this McKay has brought the tiller in directly below the upper deck beams and has the whipstaff on the upper deck. I challenge him or anyone else to show me a picture or a contemporary model of a large seventeenth century ship with that arrangement. The rudder head and tiller are always just under the middle deck on a three decker and under the upper deck on a two decker. No exceptions. All other depictions of the Sovereign where this is visible have it entering in the standard position. I wouldn't trust the stern painting for anything other than the carvings. I definitely wouldn't even consider trying to get deck placements from it. One thing that has to be kept in mind when dealing with this vessel is that it was a pioneer in size, armament and the sheer scale of its ornamentation but in other respects it probably adhered to the standards in place when it was built.

The last thing I'll mention is this. All the juggling he's done with the stern area and the decks has led to the quarter galleries being out of whack. If you look at his isometric drawing of the stern and the adjacent quarter gallery you can easily see that the gallery doesn't line up with the stern well at all. The upper stern windows are way above their counterparts on the gallery. The aftermost window on the gallery should line up with its partner on the stern. This holds true for everything that exists on both the galleries and the stern. This is the case for every model and picture of the period. Everything was always in perfect alignment. And to repeat something I said earlier - this was the king's baby. Does anyone really think that these decorative elements would not have been in perfect harmony? The shipwrights would have done whatever they had to do to make sure it all was in perfect order. All you have to do is use your head on this one.

I'll finish by saying that when I drew my plan for my model it took very little effort to make everything line up properly with flush decks. Starting 20' in front of the mizzen I gradually increased the gap between the upper main wale and the lower channel wale to get an additional 10" at the stern. I did the same between the upper channel wale and the wale above it. This was frequently done all through this period and is mentioned in a well known manuscript. When I laid in the gallery after doing this everything in this area lined up with the stern. The horizontal carving panels under the quarter gallery windows match up right on the money with their stern counterparts and so do the windows. And, yes, all the chase gun ports are in the correct positions.

One thing I'm absolutely sure of is that none of his arguments in his book will influence me to alter in any way what I'm doing with my model.

Charles Aldridge

In the acknowledgements to his book, Sovereign of the Seas 1637, John McKay thanks me for advising him on the ship's design. What he does not say is that he rejected most of what I told him, did not ask me about many subjects on which I could have offered help, and I most definitely do not want readers to think that I endorse the results.

He commits a gross error in giving an English warship of 1637 a square-tuck stern. A round tuck was adopted by English shipwrights by at least 1616, with a period of transition earlier. By 1620-23, when Sir Henry Mainwaring compiled his Seaman's Dictionary, the stern timbers and planking near the waterline in English ships were already called "buttocks" because of their convex shape. There are about a dozen careful stern view drawings and paintings by marine artists, especially Willem van de Velde the Elder, of English ships built or rebuilt in or before 1637, and one draft. All show round tucks, none square. Mr. McKay goes so far as to claim that master shipwright Sir Anthony Deane shows square tucks in his designs around 1670. They in fact show nothing whatever of the shape of their sterns. Deane's large ships all had normal round tucks as shown by numerous drawings, paintings, and dockyard models. Mr. McKay's authority for the square stern is the portrait of shipwright Peter Pett (who built the Sovereign to his father Phineas's design) attributed to Sir Peter Lely. This shows conflicting evidence; it has the knuckles of a square stern, but the stern planking is curved as in a round tuck. In square-tuck ships, the planking is dead straight and diagonal. Mr. McKay ignores the carvings design superimposed on the above-water draft by Peter Pett in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which he reproduces. This clearly shows shading at the lower corner of the stern, proving a round tuck. Why would one accept the ambiguous evidence of a Dutch portrait painter with no marine art to his credit over that of the shipwright who built the vessel? There is in fact an anachronistic painting in the National Maritime Museum, London, by Jacob Knyff portraying the ship as she appeared in the 1650s (royal arms and insignia removed); it shows a round tuck.

This book not only shows a square stern, but a bizarre square stern in which the flat portion extends below the waterline almost to the keel. This would absolutely ensure a rough, turbulent flow of water to the rudder, which would thereby be rendered quite useless. The rudder itself has problems. Its head extends partly into a huge hole in the counter as in the 18th century, and the tiller enters the hull beneath the upper deck rather than beneath the middle deck as it should. There is no sign of a sweep for the tiller and no gooseneck. From the text, the author seems not to understand that the whipstaff slid THROUGH the rowle right to its end, which is why the helm could swing 20 degrees.

The next major mistake is the falls (abrupt step-downs) in the decks. These had been condemned by the Naval Reform Commission of 1618. The designer's dimensions list for the Sovereign unequivocally states, "All the decks flush fore and aft," and Peter Pett's draft at Boston shows them flush. Why would Mr. McKay ignore direct evidence from the designer and the builder? The author is swayed by a drawing by Van de Velde the Elder showing the middle deck ports under the quarter-gallery lower than the others. Though Mr. McKay supposes this was an early drawing, it was actually made in the mid-1670s, as shown by the little bridge therein which is first mentioned at that time as running to the landing stage at the ship's mooring off Gillingham. The drawing is a copy of the decorations and features in the famous Payne engraving, superimposed on the hull Van de Velde saw in the 1670s (it is actually a cut-out pasted in over his original). That it is copied from Payne is proven by both sharing the same curious mistake: the grating over the halfdeck extends only part way up the door in the quarterdeck bulkhead. People under the grating would have had to crawl around on hands and knees, or duck-walk. The explanation is that John Payne, as known from a documentary source, drew the ship in drydock well before her launching. The grating was undoubtedly still under construction, resting on sawhorses or some such, and had not yet been raised into position. The reason for the differing height of the middle deck gunports in the Van de Velde version is that in the ship's rebuilding in 1659-60, the decks had been re-laid about 18 inches higher at the side than in the original, and the draft increased by some three feet. With the quarter-gallery thereby becoming lower relative to the deck, gunports could no longer fit under them. Two Van de Velde drawings of the Sovereign in 1673 and a painting of 1678 formerly at Lowther Castle show that there were NO middle deck gunports under the gallery after 1660. For Van de Velde to show them there as in the Payne engraving, he had to place them lower than the other ports which had been raised.

The framing shown by Mr. McKay is nothing like that of a 17th-century ship. He shows huge gaps between floors and first futtocks. For what these should be like, I recommend Richard Endsor's new book, The Master Shipwright's Secrets. This shows that the floors and first futtocks were bolted together at the frame bend stations, timbers between laid in loose, and the density of framing almost solid in the lower parts of the hull, and drastically reduced in the upper portions. This Mr. McKay could have known even from the preserved framing of the Tudor ship Mary Rose.

There are many other errors. There are no chocks at the timber heads. The riders are of 18th-century form, extended upwards by complex scarfs which weren't used for these in the 17th century. Mr. McKay shows the main pumps as brake pumps, though large English ships used chain pumps by at least the early 1620s. He shows a triple crab capstan with holes for bars on all levels, whereas English three-deckers had two double jeer capstans operated only from the upper level, and no belowdecks spindle. The position deep in the hold shown for the cook-room is improbable. If not in the forecastle or on the second deck below the forecastle, it would have been on a platform laid on false beams beneath the gundeck under the waist. Mr. McKay seems not to realize that the term "orlop" before the mid-1660s meant the gundeck. Below the orlop/gundeck, big English ships before the 1660s had heavy "false beams" supporting a series of platforms which were not a continuous deck.

Then there are the guns. Mr. McKay misunderstands the Sovereign's "drake" guns. In these the whole bore was not tapered as he supposes, but just the chamber. It was designed for small charges, so that a thin-walled weapon could fire a large-caliber ball for the gun weight. Drakes had a very short range and a violent recoil. The cannon-of-seven fired a shot weighing 42 pounds, not 60 as he says, and was in use in the Royal Navy until the mid-1780s. He also shows four-truck gun carriages, while the carriages made for the Sovereign were all drake carriages with "whole trucks and half trucks;" that is, semi-circular skids at the rear end to slow the ferocious recoil. Also, a dedicated train tackle (he indicates two per gun) was not issued to British sea gunners until the second half of the 18th century.

Even the ship's history is incomplete. Mr McKay omits three great actions in which the Sovereign took a major part: Solebay and the two Schooneveld battles, in the last of which the Sovereign was the fleet flagship for the first time. It is also untrue that Robert Lee, who rebuilt the ship in 1684-85, said her original timbers had never been changed. He said the SHAPE of the original timbers had not been changed.

Overall, this book is characterized by draftsmanship of marvelous quality, and many may buy it for that reason alone. But Mr. McKay's research was doomed by a lack of understanding of the context of his sources, and of Early Stuart shipbuilding practices. Thus, any modellists who attempt to recreate the Sovereign of the Seas based on this book are going to get badly inaccurate results.

Frank L Fox

When I first found out that this book would be published I was really enthused about it and eager to purchase it. One look at the dust jacket on Amazon, however, immediately made me skeptical. I'll explain why shortly. In spite of my misgivings I ordered the book. I had owned some of the author's previous works and admired their quality. His drafting skill is world class and I assumed that there would be drawings that would make it worth the buy. There are many excellent drawings of the ship's carvings that I like. And, as usual, all the drawings are beautifully done. Having said that I'll now move on to the bad news.

The stern on his reconstruction is an absolute joke. I'm a ship model builder and I've been researching this ship for a long time. Throughout this research I've had the help of experts who are unquestioned authorities on the seventeenth century royal navy. I'll take opinions from people like that any day. They've devoted their lives to this and can access information that few people are even aware of. That includes the author of this book. I can assure you that my opinions about this ship are the same as theirs.

I'll deal with the square tuck McKay favors first. For those not familiar with the term it refers to the area immediately below the wing transom. This is also sometimes called the main transom. I've included a picture of an actual square tuck on a 4th rate ship of about 1691. Ships of this size and smaller sometimes had these tucks but larger ships never. You can clearly see the planking on the tuck. The author comes to his conclusion about the square tuck on the Sovereign on some rather flimsy evidence. There is a well known painting which includes a view of the stern of this ship. This picture is the only evidence of any kind that supposedly shows a square tuck. The problem is that it's impossible to tell what it really means. I've attached an enlargement of the picture so you can follow me. At first glance it does look as if it shows a square tuck. On further inspection, however, you'll notice that the planking on the tuck is curved. And the curves of the plank are angled exactly the way they would be for a round tuck. A square tuck would have straight planks just as they are on the 4th rate model. It's hard to say what's going on here. The artist may have been confused about what he was looking at. Who knows? What I do know is this. This painting is worthless as proof of anything because it seems to show two different things for the same area. Of course McKay has taken care of this little problem by simply making the planks straight on his reconstruction drawing taken from the painting. The evidence for a round tuck is pretty straightforward. The preliminary draft for the ship has this area shaded in a way which clearly means rounded. McKay seems to think that the round tuck was something unusual at the time when the Sovereign was built but there are several pictures of large ships built between 1623 and the year she was launched and they all have round tucks. From that period and to the end of the century there are no pictures and no models of large ships with anything but round tucks. None. That includes the Sovereign. It would appear that during that time the round tuck had become the standard for 3rd rate ships and above. It's hardly likely that they would have backslid and put an outmoded stern on a ship of this importance. Especially since it happened to be the king's pet project. And one more thing to finish this subject. Not only does McKay give the ship a square tuck but he continues the flat stern all the way down to the keel! Neither I nor anyone I've talked to about this has ever seen such a stern on any seventeenth century English ship. Possibly he could explain how a clean run of water would get to the rudder.

The second item I totally disagree with are the falls in the decks. I believe that he primarily bases his deck fall theory on the Van de Velde drawing that was done somewhere around 1661. The drawing is obviously based to a great extent on the Payne print which was done right after the launch of the ship. The two aftermost middle deck gun ports in this drawing are well below the others. The ship was launched in 1637 and had documented rebuilds in 1651 and 1659-1660. The deck heights were definitely altered in the last one. So the artist couldn't have ever actually seen it in its original form and that's what we're concerned with here. Obviously, the drawing cannot be considered a reliable source of information for the ship in its early form. This one drawing is the only indication of anything but flush decks in any visual representation of the ship. All other drawings starting from the original draft and going on to the last ones later in its career show flush decks. The preponderance of the evidence is definitely in favor of flush decks. And one more thing. The biggest English ship before the Sovereign was the Prince Royal which launched in 1610 and it also was designed by Phineas Pett. It did have deck falls but these were deemed unnecessary by a 1618 commission and the ship was given flush decks in a 1623 alteration.

And now we turn our attention once more to the stern painting that McKay has such great faith in. This rendition of the stern is far from perfect but I'm simply going to concentrate on one of them because I know it caused what I and the experts consider a massive blunder. In the painting the rudder head is shown as being above the middle deck chase ports. From this McKay has brought the tiller in directly below the upper deck beams and has the whipstaff on the upper deck. I challenge him or anyone else to show me a picture or a contemporary model of a large seventeenth century ship with that arrangement. The rudder head and tiller are always just under the middle deck on a three decker and under the upper deck on a two decker. No exceptions. All other depictions of the Sovereign where this is visible have it entering in the standard position. I wouldn't trust the stern painting for anything other than the carvings. I definitely wouldn't even consider trying to get deck placements from it. One thing that has to be kept in mind when dealing with this vessel is that it was a pioneer in size, armament and the sheer scale of its ornamentation but in other respects it probably adhered to the standards in place when it was built.

The last thing I'll mention is this. All the juggling he's done with the stern area and the decks has led to the quarter galleries being out of whack. If you look at his isometric drawing of the stern and the adjacent quarter gallery you can easily see that the gallery doesn't line up with the stern well at all. The upper stern windows are way above their counterparts on the gallery. The aftermost window on the gallery should line up with its partner on the stern. This holds true for everything that exists on both the galleries and the stern. This is the case for every model and picture of the period. Everything was always in perfect alignment. And to repeat something I said earlier - this was the king's baby. Does anyone really think that these decorative elements would not have been in perfect harmony? The shipwrights would have done whatever they had to do to make sure it all was in perfect order. All you have to do is use your head on this one.

I'll finish by saying that when I drew my plan for my model it took very little effort to make everything line up properly with flush decks. Starting 20' in front of the mizzen I gradually increased the gap between the upper main wale and the lower channel wale to get an additional 10" at the stern. I did the same between the upper channel wale and the wale above it. This was frequently done all through this period and is mentioned in a well known manuscript. When I laid in the gallery after doing this everything in this area lined up with the stern. The horizontal carving panels under the quarter gallery windows match up right on the money with their stern counterparts and so do the windows. And, yes, all the chase gun ports are in the correct positions.

One thing I'm absolutely sure of is that none of his arguments in his book will influence me to alter in any way what I'm doing with my model.

Charles Aldridge

Wow, that's a lot to take in. You could make a career out of studying the sweeps and hollows that make up the body form. For my purposes, an approximate is good enough, with care taken to accurize the kit parts within reason. It's not like I'm to test the hydrodynamic behavior of this ship in a wave tank.CharleyT was right in his previous post. On further consideration of the reviews of John McKay's book by Frank L. Fox and Charles Aldritch, I find it hard to trust ANY of the conclusions that John McKay made regarding the construction of SoTS. The amounts of errors I counted among the reviewers, plus what I know as a Marine Engineer myself, have eroded my confidence in the author greatly. I have seen one other author write a book that became touted as the definitive book on the subject, found in every major library in the world, yet was so inaccurate that any who followed it would be seriously misled making reproductions from it. That book is The Crossbow by Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey in 1903. It pains me that John McKay's book will likely become similarly popular and most people seeking to learn about HMS Sovereign of the Seas will not see past the pretty pictures and drawings to learn how many historical sources he ignored, as well as advise from current experts, and how he misinterpreted those sources he did utilize. I encourage those who have purchased McKay's book to likewise read the book reviews on Amazon. Their arguments are well founded. Gather as much information from other sources as you can. After reading McKay myself, I found myself asking why he insists that the hull shape was so fine, because he doesn't back up his opinion with information on that point. For me, the doubts all started with that ridiculous stern and the unnecessary "officer's companion way" located immediately adjacent to another companion way, both leading from the weather deck down to the upper deck. Why would you need TWO ladders in the place? As an ship's officer myself, I would think my fellow officers were never elitist enough to not suffer treading the same ladder as the crew. I'm now thinking that the only changes I should make to the DeAgostini frames would be to sand some flatter spots between the turn of the bilge and side of the hull as shown below.

View attachment 194505

The key questions that come up are, how strong were the hollowing curves adjacent to the keel, how flat was the bottom (what was the approximate angle of incidence of the bottom near the keel), and how sharp were the curves at the turn of the bilge? Which set of information looks the closest to the Pett design between DeAgostini, John McKay, your Royal Sovereign model and the Amato plans which I have? Looking for the simplest answer. Basically, I have to choose one, and slightly modify the DeAgostini frames to match at close as is practical. Please do not shy away from expressing your opinion. No penalty if the ship end up looking fake like the Black Pearl, that's on me.

The key questions that come up are, how strong were the hollowing curves adjacent to the keel, how flat was the bottom (what was the approximate angle of incidence of the bottom near the keel), and how sharp were the curves at the turn of the bilge? Which set of information looks the closest to the Pett design between DeAgostini, John McKay, your Royal Sovereign model and the Amato plans which I have? Looking for the simplest answer. Basically, I have to choose one, and slightly modify the DeAgostini frames to match at close as is practical. Please do not shy away from expressing your opinion. No penalty if the ship end up looking fake like the Black Pearl, that's on me.

Last edited:

Good to hear your comments about McKay. I, too, bought the book, and I wasn't happy with it. It does, however, make a pretty good doorstop.Wow, that's a lot to take in. You could make a career out of studying the sweeps and hollows that make up the body form. For my purposes, an approximate is good enough, with care taken to accurize the kit parts within reason. It's not like I'm to test the hydrodynamic behavior of this ship in a wave tank.The key questions that come up are, how strong were the hollowing curves adjacent to the keel, how flat was the bottom (what was the approximate angle of incidence of the bottom near the keel), and how sharp were the curves at the turn of the bilge? Which set of information looks the closest to the Pett design between DeAgostini, John McKay, your Royal Sovereign model and the Amato plans which I have? Looking for the simplest answer. Basically, I have to choose one, and slightly modify the DeAgostini frames to match at close as is practical. Please do not shy away from expressing your opinion. No penalty if the ship end up looking fake like the Black Pearl, that's on me.

As to how flat the bottom was, as you know, this varies. Because of the dead rising, it will never be perfectly flat, even at the midship bend, which is were the bottom would be the flattest. I can't give you an exact angle, but somewhere in the neighborhood of about 15 degrees, give or take a few, should do it for this bend. Also, the "cartoon" of the midship bend that I posted will give you an idea of how much to change the shape of the De Ag. bends, should you choose to do so. My bend is based on figures given by Pett, so it's pretty accurate

Maarten, the lack of scale on the diagram I provided may make the different bends look more similar than the actually are. The difference between Deane's and Pett's midship bends are a bit over 2 feet for the floor and for the radius of the futtock sweep. Deane's design gives a much fatter ship.

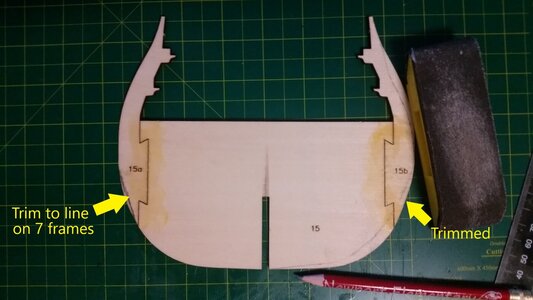

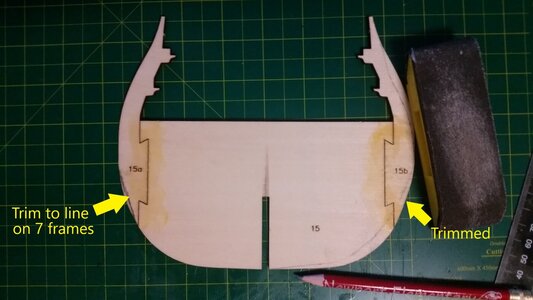

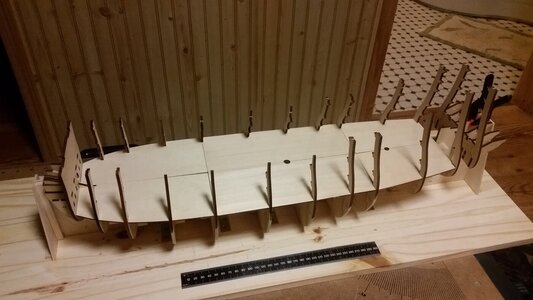

Reinforcement pieces of plywood were added to each side of the false keel over each of the keel joints to strengthen them. Then, very subtle trimming was done on the seven frames closest to midships. Five are shown below. Approximately 1mm of wood was taken off the edges to create a flatter area between the first futtock and the waterline. Not very much wood was removed in order to preserve the overall shape of the DeAgostini hull design, yet show a hint of the Peter Pett sweeps. The resulting hull will be a tad closer to the Pett sweeps, although the DeAgostini Hull has wider floors, making it slightly wider at the bottom. I think I can live with this hull shape and move on.

Hi Kurt

Good luck with your build,you will have fun with this one,I know I did when it comes to the geometry.It is seven years since i was working on mine and have forgotten a lot of the details but here is a synopsis of what I changed in short;

Deck sheer-too flat OOTB

Lowered the lower deck

Changed to proper round tuck

Changed the hull cross section starting around 8 inches from the stern working backwards to get the correct profile at the stern.Kit is too fat and not tall enough.

Changed to offset bowsprit.

I went for the stepped deck,I personally believe it was so.

Lastly there is no right or wrong with this one,until someone invents a time machine,there are only educated guesses.However,I do disagree with many of McKays conclusions.Sovereign was a one off,she didn't follow any standard practices of the time.There is a document in existence from the time that actually states the hull was DOUBLE planked!It is mentioned in James Septon's book.

Kind Regards

Nigel

Good luck with your build,you will have fun with this one,I know I did when it comes to the geometry.It is seven years since i was working on mine and have forgotten a lot of the details but here is a synopsis of what I changed in short;

Deck sheer-too flat OOTB

Lowered the lower deck

Changed to proper round tuck

Changed the hull cross section starting around 8 inches from the stern working backwards to get the correct profile at the stern.Kit is too fat and not tall enough.

Changed to offset bowsprit.

I went for the stepped deck,I personally believe it was so.

Lastly there is no right or wrong with this one,until someone invents a time machine,there are only educated guesses.However,I do disagree with many of McKays conclusions.Sovereign was a one off,she didn't follow any standard practices of the time.There is a document in existence from the time that actually states the hull was DOUBLE planked!It is mentioned in James Septon's book.

Kind Regards

Nigel

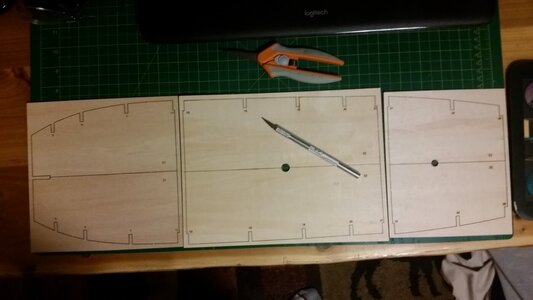

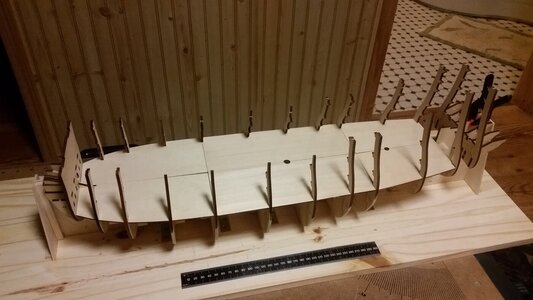

While the frames are drying, the lower gun deck pieces were cut out and place loosely into place in order to hold the frames precisely in place while the glue dries to full hardness. That will prevent the frames from getting funny ideas and trying to warp out of position. It was noted that the bow false keel piece and the one immediately behind it have a very slight twist. It is critical to either soak bend and dry these pieces back into shape or make sure that later parts which will hold them straight are glued precisely into position. Another builder who's La Couronne build log was my major guide in building that ship, failed to properly jig and hold the keel pieces, which were badly twisted. The result showed up later with a twisted forecastle and a bitter lesson was learned. Still, his model is one of the most beautiful ships I have ever seen and was the inspiration for my first ship. See below.

Isn't she just gorgeous? La Couronne Build by EJ.

“If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants” - Isaac Newton

Thanks EJ!

The lower deck pieces are cut out.

Now these deck plates will NOT be glued down in place as instructed in the instructions. Right now they are only there to hold the frames in position along with the keel jig. Orginially, this deck would be glued down and solid wood bulwark pieces glued to the inside edges of the frames. The bulwarks would be painted black and false half cannon barrels stuck into them later in the build. Instead, LET THE BASHING BEGIN! The decks will be soaked and bent to form a proper camber shape. Each frame beneath will be built up to a curve of the camber to support the new deck shape.

Then, the decks will be glued down onto the curved support surfaces offered by the modified frames. An alternative is to add the camber support strips like Röler did and apply deck sections made of strips like he did. The deck will be either planked or a shortcut utilizing planks textures thin wood will be applied and detailed.

Then, a frame structure for the deck above it will be constructed from basswood, similar to Roland Röler's build shown below.

The upper decks will be fashioned the same way. You should be able to peer into the cannon ports on any deck and see The overhead beams, something like this, because faint LED lights will be installed on all decks. Other internal fittings like capstan parts, ladderways, chain pumps, etc. will also be fitted using all the information I can find.

This is the plan. May God grant me the patience to see it through.

Isn't she just gorgeous? La Couronne Build by EJ.

“If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants” - Isaac Newton

Thanks EJ!

The lower deck pieces are cut out.

Now these deck plates will NOT be glued down in place as instructed in the instructions. Right now they are only there to hold the frames in position along with the keel jig. Orginially, this deck would be glued down and solid wood bulwark pieces glued to the inside edges of the frames. The bulwarks would be painted black and false half cannon barrels stuck into them later in the build. Instead, LET THE BASHING BEGIN! The decks will be soaked and bent to form a proper camber shape. Each frame beneath will be built up to a curve of the camber to support the new deck shape.

Then, the decks will be glued down onto the curved support surfaces offered by the modified frames. An alternative is to add the camber support strips like Röler did and apply deck sections made of strips like he did. The deck will be either planked or a shortcut utilizing planks textures thin wood will be applied and detailed.

Then, a frame structure for the deck above it will be constructed from basswood, similar to Roland Röler's build shown below.

The upper decks will be fashioned the same way. You should be able to peer into the cannon ports on any deck and see The overhead beams, something like this, because faint LED lights will be installed on all decks. Other internal fittings like capstan parts, ladderways, chain pumps, etc. will also be fitted using all the information I can find.

This is the plan. May God grant me the patience to see it through.

Last edited:

You lowered the lower deck? The deck I'm planning on right now? I guess I better learn why and determine how far it needs to be lowered or the gun ports are going to be out of place later on. Can you provide some details, pictures even? I'm still in the MASSIVE INFORMATION GATHERING phase. If changes for accurization and improvement are to be made, better they be known earlier than later! Any information you can provide will be devoured as if I were starving. The offset bowsprit has been prepared for, the tuck changes are a way off yet, and the camber amount I can estimate without too much measurement. (La Couronne was modified to have deep camber on all upper decks). I will not install a stepped deck, because of a mistake I learned of in the drawings of Willem van de Velde the Elder. He apparently copied the gun port located under the side gallery from Payne, and applied it to his drawing of the ship AFTER the decks were internally rearranged from their original positions. Those guns were removed during the rebuild of the ship. See Frank L. Fox's information in Post #32 above for details. McKay copied this error and since the guns could not be placed in logical height with the NEW deck locations, he provided falling decks (stepped) to accommodate the guns. Falling decks were outlawed. Peter Pett was instructed by authorities NOT to install any falling decks in SotS when it was first constructed. All decks in my version of SotS, the version of 1637, will be continuous and the guns places accordingly. Also, my ship will be painted black to the waterline like in the Lely painting, unless someone can tell me that the painting only LOOKS black that low on the hull, but isn't. My model won't look as pretty in all black and gold, but I'm trying to make it as close to the day it first set sail as information will allow. Right now, there is no information that says only the top ornamented sections of the ship were black. And I have no doubt they might have changed the paint scheme during the first rebuild to save some money.Hi Kurt

Good luck with your build,you will have fun with this one,I know I did when it comes to the geometry.It is seven years since i was working on mine and have forgotten a lot of the details but here is a synopsis of what I changed in short;

Deck sheer-too flat OOTB

Lowered the lower deck

Changed to proper round tuck

Changed the hull cross section starting around 8 inches from the stern working backwards to get the correct profile at the stern.Kit is too fat and not tall enough.

Changed to offset bowsprit.

I went for the stepped deck,I personally believe it was so.

Lastly there is no right or wrong with this one,until someone invents a time machine,there are only educated guesses.However,I do disagree with many of McKays conclusions.Sovereign was a one off,she didn't follow any standard practices of the time.There is a document in existence from the time that actually states the hull was DOUBLE planked!It is mentioned in James Septon's book.

Kind Regards

Nigel

About the camber of the decks......

You can calculate the camber for the Treatise. Skipping the arithmetic and getting to the results for the Sovereign:

Camber of lower gun deck: 18 inches

Camber of middle gun deck: 12 inches

Camber of upper gun deck: 8 inches

Nobody knows the camber of the upper decks, but 8 inches is a good guess.

You can calculate the camber for the Treatise. Skipping the arithmetic and getting to the results for the Sovereign:

Camber of lower gun deck: 18 inches

Camber of middle gun deck: 12 inches

Camber of upper gun deck: 8 inches

Nobody knows the camber of the upper decks, but 8 inches is a good guess.