To support your ambition, I offer my evolution in thinking:

Most NMM plans are 1:48 (museum scale). Building at 1:48 offers an opportunity for a lot of detail. If the ships-of-the-line are your interest, a 1:48 model of one tends to be a Baby Huey to live with.

I do not wish to lose the opportunity for detail. I decided that half museum scale would be a reasonable compromise. A model is a 3D object. One half the volume of 1:48 is 1:60 (rounding off). A 50% hull will still occupy a lot of space. I wish my production to be of a family. All are 1:60.

I experimented to see if my POF method would work at smaller scales.

I did a test at 1:120 - the volume is 6.4% of museum. It was a success. It was much faster and inexpensive in wood stock. A fleet would not be overwhelming to display. Everything but the framing would require a special set of skills. Those skills are not my want. I am set in my ways and will stick with 1:60.

To push the limits, I framed a hull at true miniature scale 1:192. The volume is 1.5% of museum. Reed's method of framing is a bit of a challenge. I built the rough framed hull fairly easily. It was quick to do. My eyes, attention, and not as steady hand are not up to the fine shaping part. The rest of it is way too special to attempt as a beginner miniaturist at 79 years old.

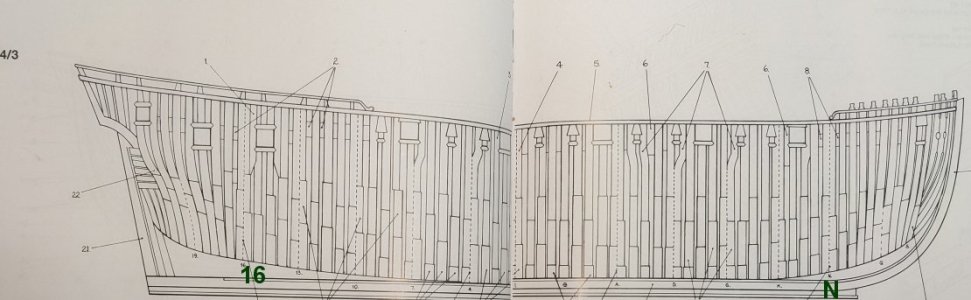

I did my 1:20 test using ANCRE Philippe 90 1693 - using timber patterns that I lofted:

View attachment 556771

Solid *** All bends-space=frame *** Navall Timber framing-space all in F1 (navall timber) frame *** Navy Board space alternates frames

Each segment is a station to station sandwich/section of frames.

I did not try singleton filling frames. It would be no more difficult to do than the above. I dislike butt chocks. I hate end grain to end grain bonding. It is not bonding at all. Were I looney enough to do it, I would not remove the space filling timbers until the internal thick stuff and or outside ribbands are in place to support the timbers.

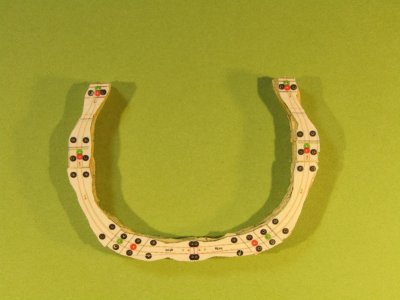

View attachment 556773

The frames assembled.

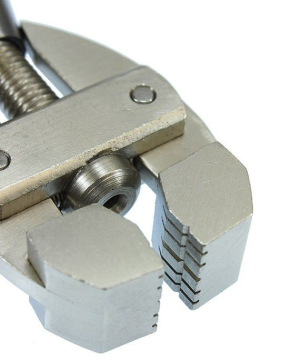

View attachment 556774

Glued into a station sandwich - the spaces have temporary Pine filling timbers - using an adhesive easily broken using a solvent that does not harm the main PVA bond (easy to say - not so easy to develop)

View attachment 556775

sanded

View attachment 556772

Space fillers removed.

For the 1:192 trial, I chose Ajax 74 1767

View attachment 556776

A station sandwich

View attachment 556777

Sanded

The sanding of it was so hairy a job that I decided that the hull:

View attachment 556778

Would be better is stored in a drawer.

So, your 1:120 Granado is readily doable if care is taken.