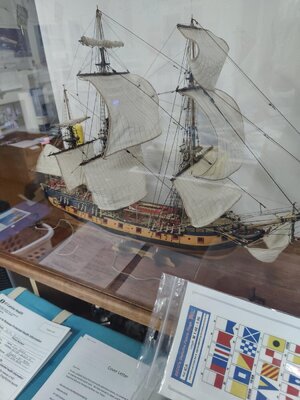

Long story short: No, USS Rattlesnake did not utilize international code signals because they were invented later, as was Howe's 1790 code because the ship existed in 1783. If signal flags were used, instead of the traditional method of relaying instructions by boat messenger, it may have been an earlier system used by the British, or a unique set of coded numerical signals created by the Americans to prevent British message interception.

What Google found:

In 1738, Mahé de la Bourdonniase, a French officer, developed the first numerical flag code, which served as the basis for later flag-hoist signaling. The numbering system vastly increased the combinations of communications a ship could make to 1,000 using three flags.

Modern naval code signalling began with the invention of maritime signal flags in the mid-17th century by the then-Duke of York (subsequently James II) who was created Lord High Admiral after the Restoration.

For US Ships:

he development of marine signaling in the United States Navy during this period paralleled that in Great Britain. Commodore Thomas Truxtun published a set of Instructions, Signals and Explanations Ordered for the United States Fleet in 1797, which was basically a numerary system along the lines of Howe's 1790 code. In 1809, however, Commodore David Porter issued a signal book to his squadron that went a small step beyond the Popham system. Once again, the basic signals were numerical, but rather than simply numbering the letters of the alphabet, Porter's letters involved hoisting the numeric flags inverted or in combinations that did not match their position in the alphabet. For example, the number 1 was signified by a solid red flag, but the letter A was divided horizontally blue over white. The letter K was not a combination of the 1 and zero flags, but of A and I. The randomness of the Porter code would have added considerable difficulty to an enemy's efforts to decipher a message. Like their British counterparts, however, Truxtun and Porter's systems were basically numeric--the numbers keyed to words and phrases in the code book--although from Porter's code onward there was also the capability to send "telegraphic" messages by spelling out individual words letter-by-letter. As in the Royal Navy, successive editions of the signal books contained the same basic flag designs, but with the numbers assigned to them rearranged. The purpose of these changes was clear--to guard against compromise of this sensitive tactical communications information. For the same reason, signal books were bound with heavy lead plates bolted to the covers so that they would sink to the bottom if a captain had them thrown overboard to prevent their capture.

In 1817, Captain Frederick Marryat of the Royal Navy published his Code of Signals for the Merchant Service. Based on the 1799 naval code, it was also a numeric system, but with a vocabulary oriented more toward commercial and less toward naval needs. Marryat's code was widely accepted, and by 1854 was known as the "Universal Code of Signals." In the United States, a number of codes were developed for the merchant marine, including James M. Elford's Universal Signal Book (1818), Richard Berrian's American Telegraphic and Signal Book (1823), and J. R. Parker's American Signal Book (1832). Parker's system was updated and improved in a number of successive editions and was eventually succeeded in 1847 by Henry J. Rogers' Rogers and Black's American Semaphoric Signal Book for the Use of Vessels Employed in the United States Naval, Revenue and Merchant Service. As the title suggests, this volume was the first commercial signaling system adopted for use by the government for non-tactical communications. Rogers continued to publish revised editions of this work under various titles until 1856. A year later, a breakthrough in the science of marine communications made Rogers' system obsolete.