In that case I should understand what happens here and I simply don't.

-

Win a Free Custom Engraved Brass Coin!!!

As a way to introduce our brass coins to the community, we will raffle off a free coin during the month of August. Follow link ABOVE for instructions for entering.

-

PRE-ORDER SHIPS IN SCALE TODAY!

The beloved Ships in Scale Magazine is back and charting a new course for 2026!

Discover new skills, new techniques, and new inspirations in every issue.

NOTE THAT OUR FIRST ISSUE WILL BE JAN/FEB 2026

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Samuel 1650 – a Dutch mid-17th century trader

- Thread starter -Waldemar-

- Start date

- Watchers 21

I am trying to follow these exciting explanations with great interest. Unfortunately, my knowledge of English is too poor to adequately understand the original articles and the details of the translations are very questionable in some places.

Please allow me to ask two questions.

1. Why is the outer end of the flax outside the frame contour in the area of the bilge arch? Why does this begin within the flat?

2. the lines of the ship being discussed here make me think very much of those of the Scheurrak SO1. There I was very surprised at the deepest width. what do you think?

greetings

Please allow me to ask two questions.

1. Why is the outer end of the flax outside the frame contour in the area of the bilge arch? Why does this begin within the flat?

2. the lines of the ship being discussed here make me think very much of those of the Scheurrak SO1. There I was very surprised at the deepest width. what do you think?

greetings

The drawings that were made of the Scheurrak wrack were done by an intern and have no scientific value at all.2. the lines of the ship being discussed here make me think very much of those of the Scheurrak SO1. There I was very surprised at the deepest width. what do you think?

.

True, however, in these examples, it was not a question of the relationship of length to depth, but rather the juxtaposition of depth in hold with the level of the greatest breadth of the master frame. I have completed this below:a ship 154 x 38 x 17'3" (x 16 feet; „at 16 feet from the keel, the frame has its greatest breadth”)

a ship 155 x 36 x 17 (x 17 feet; „at 17 feet its greatest breadth”)

a fluitschip 140 x 34'3" x 14'6" (x 12'6"; „the greatest breadth at 12'6"”)

a spiegelschip 85 x 22 x 11 (–)

a hooker 72 x 18 x 10 (x 8; „and the ship has its [greatest] breadth at 8 feet”)

.

You are right.

.

1. Why is the outer end of the flax outside the frame contour in the area of the bilge arch? Why does this begin within the flat?

This is the result of a specific sequence of geometric frame contour creation. In this case, the „flat” and the futtock sweep were drawn first, and only later the bilge sweep was added (here the reconciling sweep is also added). Sometimes without shortening the „flat” curve (then tangentially to the futtock sweep only, creating a kink at the junction of the bilge sweep and the „flat”), but even more often with shortening the curve of the „flat” (tangentially to both the futtock sweep and the „flat”). Perhaps it is most convenient to see this in my other threads about Dutch, Swedish and Danish ships. You can easily find them – they are all on this forum in the same topic section.

.

Very interesting discussion. Isn't this the case with every single deck vessel or maybe even fluytschepen with only a small "koebrug" deck that the deck at greatest breadth is missing.

Are there in these single deck ships additional riders installed to secure the structural integraty?

As far as I know these are not present in the wreck.

Are there in these single deck ships additional riders installed to secure the structural integraty?

As far as I know these are not present in the wreck.

.

Very interesting discussion. Isn't this the case with every single deck vessel or maybe even fluytschepen with only a small "koebrug" deck that the deck at greatest breadth is missing.

Are there in these single deck ships additional riders installed to secure the structural integraty?

As far as I know these are not present in the wreck.

Indeed, this must have been a fairly common configuration. Such merchantmen could be built quite lightly, even without riders, at least for calm, easy or inland waters, and the entire, sparse crew could be accommodated quite comfortably in the aft room.

It is interesting that the term koebrug has dramatically changed its meaning over time. At first, one of the highest decks was called so, and later one of the lowest. It seems that in the Baltic basin the former meaning has persisted much longer.

.

.

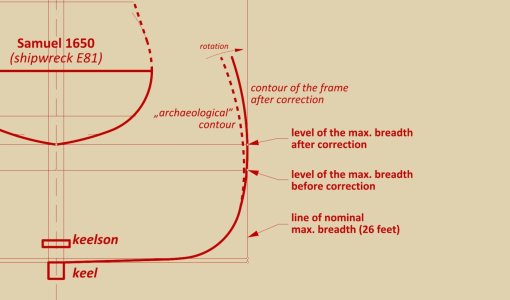

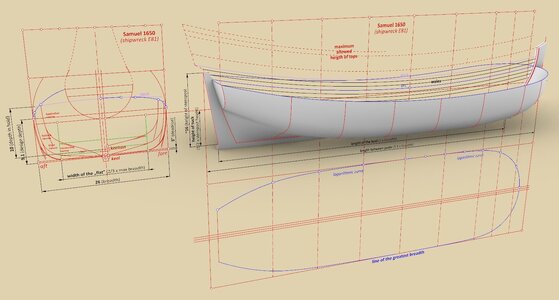

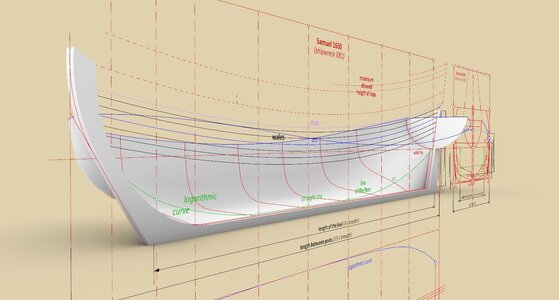

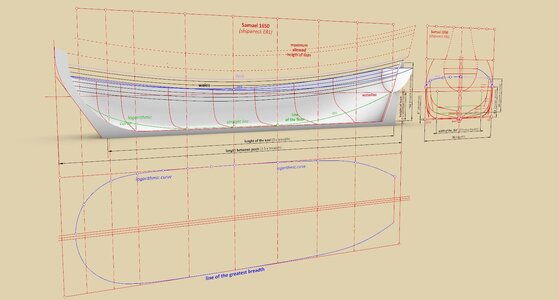

The discussion so far, in public and in private (thanks Ab and Maarten for your active participation), has led me to give Samuel 1650 another, second look. It turns out that, by deciding to be bolder than before in correcting the distorted (but to an unknown extent) archaeological material, reconstructive results closer to the more common proportions known from the written sources can be obtained.More specifically, I opted, as before, for the procedure of spreading outwards (presumably) the previously collapsed inwards sides of the ship, but this time in an angular manner (as opposed to the horizontal shifting), shown in the diagram below.

Such seemingly minor adjustment to the contours of the frames, however, with this particular specificity of the curvature of their shapes, results in quite profound changes to the geometry of the main design lines and other relationships important to the ship's design intent, specifically by:

– raising the greatest breadth of the hull in the midship region, effectively increasing the design depth from six to eight feet,

– aligning the levels of design depth and height of tuck, which is in turn closely related to the design draught level,

– increasing the radii of futtock sweeps by half,

– finally, such treatment made it possible to apply with very good results the method of division of a hull length known in detail from other, source designs made in the Dutch tradition.

As a general result, the overall geometric design of the Samuel 1650 gains significantly in overall coherence and conceptual soundness, however, without changing the previous assessment of this vessel as a flat-bottomed coaster featuring relatively shallow draft.

Let’s start again with a presentation of the design reconstruction of Samuel 1650 in this second iteration...

.

Thank you Waldemar for applying second thoughts to your original design. This marks the great scientist.

I am very much relieved that the method I so far believed in so deeply was not exposed as being nonsense. I had a bad night over it.

In general I think one can say that every Dutch vessel combined a flat bottom and a relatively shallow draught.

I am very much relieved that the method I so far believed in so deeply was not exposed as being nonsense. I had a bad night over it.

In general I think one can say that every Dutch vessel combined a flat bottom and a relatively shallow draught.

Of course I should have said Dutch cargo vessels. My bad.

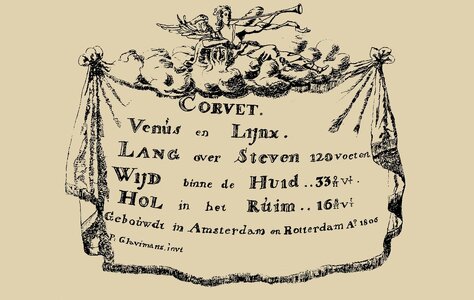

Besides, a corvet is not a vessel of Dutch origin. But of course you knew that.....

Besides, a corvet is not a vessel of Dutch origin. But of course you knew that.....

Last edited:

.

Besides, a corvet is not a vessrl of Dutch origin. But of course you knew that...

!??? ... But sharp shapes were by no means reserved exclusively for corvettes, but to varying degrees, as far as possible and according to specifics also in other types of (war)ships. In your book In Tekening Gebracht I quickly found a reproduction of a design of undeniably Dutch origin (Hof St. Janskerke 1733 by genuine Dutch shipwright Paulus van Zwijndregt, using his own proprietary design methods). The lines of this ship are also sharp. Perhaps less so than those of Venus & Lynx 1806, but certainly this ship cannot be called flat-bottomed and featuring shallow draught.

Yes, I know, now I'm going to hear that warships aren't an originally Dutch invention either, but since we're making jokes like that...

.

I give up on that...

.

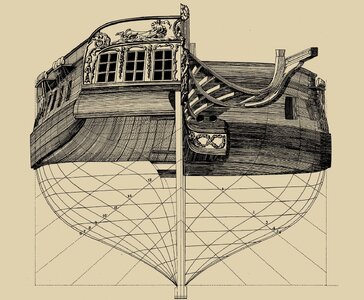

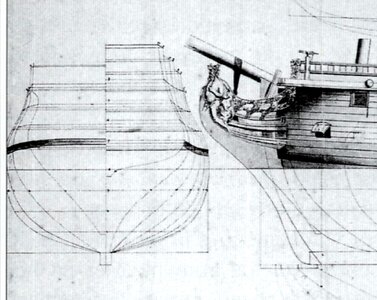

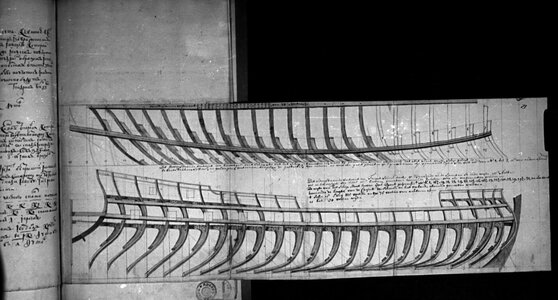

To all Russian (and non-Russian) readers:From which manuscript (apparently in Russian) and in particular from which year is the reproduction of the plan below, apparently of Dutch origin (unlike the main text, the description of the plan itself is in Dutch).

This copy was kindly provided by Ab, however, without this vital information, which was lost somewhere along the way.

.

.

In the end, the revisions in the second iteration are even a little more far-reaching than I had expected before, but at the same time I am enormously satisfied with the results I have now obtained – the conceptual construction that has been found is extremely internally coherent and at the same time has been achieved by the simplest possible geometrical design means.But that's not all – this second reconstruction has also found a whole set of design proportions in which the interrelationships are not only expressed in round ratios (numbers), but are at the same time in accordance with the typical proportions provided by the source shipbuilding manuals, both in the form of recommendations as well as very numerous examples of specific constructions from the period. One simply could not want for more.

I must also make it clear that, with the new proportions found in the second approach, I no longer consider this ship to be a specialised coastal vessel, but a deep-water merchant ship fully capable of traversing the ocean (I will ask the administrators to change the thread title accordingly, by replacing the term „coaster” with „trader”).

And just to graphically show the work still in progress:

.

Last edited:

To me this looks entirely in accordance with the rules from our literature. That is most reassuring, both for our trust in the original sources and for your techniques and methods.

Back to a quiet night's rest.

Back to a quiet night's rest.

.

Thank you very much, Ab. Actually, the only source of uncertainty in this case was the unknown extent and nature of the archaeological deformation, as well as the rather inconsistent archaeological documentation (unfortunately, it is not a precise 3D scan). The problem was definitely not with the sources, nor with 'my' method, which in fact also follows directly from the sources.It is curious that in the 40 years since the archaeological documentation was drawn up in graphic form, no one has examined this immensely important find in a similar way. Everyone has so far been content with rough estimates, rather esoteric philosophising, smoothing out shapes by eye or at best using fairing waterlines or diagonals, precisely against the sources of the period.

.

Once you are finished I would really appreciate a lines plan of thgis vessel. Together with the Witsen pinas and some VOC ships at the end of the 17th century it is the only hull we can be sure of.

OH WOW, WOW WHAT AN EDUCATION THIS THREAD IS NOW IF ONLY WE CAN GET SOME KITS/SEMI KITS OF THESE SMALLER DUTCH VESSELS. GOD BLESS NSTAY SAFE ALL DON