.

Many thanks, Arthur, for your comment.

First of all, it must be said that one must be very cautious, but at the same time – which is inevitable – extremely flexible when it comes to the meaning of specific terms, which in itself is somewhat contradictory and, as a result, further exacerbates the difficulties of interpretation. In any case, this rather loose and ambiguous use of these old terms is particularly evident when comparing Portuguese texts on shipbuilding from that period. In addition to Fernandes' own description, I am also referring to the works of Fernando Oliveira and João Baptista Lavanha.

For example, the term “revessado” or “reversado” can mean both a fashion piece and the lower parts of the frames in the rear of the hull, or the term “côvado” can mean both floor sweep and just sirmark on the floor sweep, or “caverna (mestra)” can mean (master) frame or (master) floor timber, or a frame could also be called “madeira” or referenced as “a pair,” and in such circumstances, attempts to rigidly adhere to only one meaning of a given term can easily lead one astray, and it is only the context of its use that proves decisive, and yet with the additional caveat that this context is not necessarily always clear at all, especially when one takes into account the almost complete lack of punctuation, the crazy, archaic syntax, or the author's mental shortcuts.

The term “forma” also fits quite well into the above scheme, and can have a whole range of diverse, more or less synonymous meanings, and here, in Fernandes' description, it can mean both a complete set of “templates” or “moulds” for the entire frame, consisting of several elements, as well as individual components of this set, such as “forma do braço,” meaning “futtock template.”

Fernandes implies quite strongly that the forma, which means mould/form, is the thing to be divided

In this excerpt from Fernandes' description, which you quote above, in my opinion, the division into five does not refer to the number of components of the entire master frame template set, but to the dividing of the hull length for the allocation of numbered frames, for at least three reasons:

— first, three templates are sufficient rather than five in the geometric arrangement of the master frame of the patacho. This naturally refers to one side of the hull (it is unlikely that two sets were used separately for both sides of the hull, as this would have made it even more difficult to maintain the much-desired symmetry). So, apart from a possible template for bottom/hollowing curves applied later, these would be moulds for

cavernas, braços, and hastes (floor timbers, futtocks, and toptimbers, respectively), partially overlapping each other. Admittedly, there are also aposturas (2nd futtocks), but here they are essentially of the same curvatures as

braços and

hastes,

— secondly, if we assume that this division into five would nevertheless refer to the number of components of the frames template entire set, and not to the division of the keel into five parts, then the next passage, i.e. “nas duas porao a madeira” (or, in English, “in the two the frames will be set”), would remain without context and meaning,

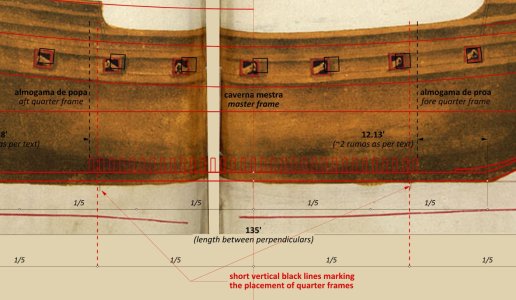

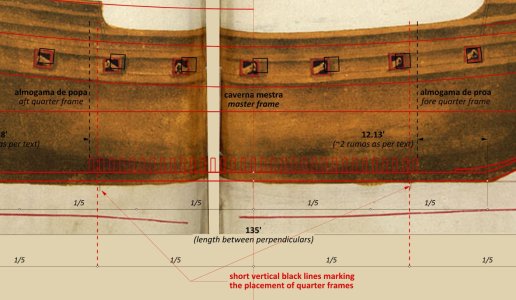

— thirdly, finally, analyzing this draught graphically, I found that the markings made by Fernades, indicating the placement of both quarter frames, are located quite precisely in accordance with the division of the hull into five parts, as shown in the graphic below:

* * *

It should come as no surprise that the term “a pair” can also be problematic. Here, it can mean either 2 x 16 frames, i.e. 16 on both sides of the master frame, but it can also mean 16 frames on one side of the master frame, because Portuguese shipbuilders used the term “a pair” to refer to a complete frame (i.e. more in the sense of the English “bend”). “A pair” because it consisted of two layers of timbers laid alternately (floors, futtocks, toptimbers), alternatively, this term could also express the arrangement which in English is expressed by the term “timber and room” or “room and space.”

The “notches” at the contours of the frames, on both sides of the keel, which you mention above, are nothing more than “côvado” in the sense of sirmarks on the bilge sweep.

Lastly, only three of the sixteen pairs are to undergo the galivar process at some point, which I don't have a guess as to what that means in this context, and is something you also left out.

It's very good that you noticed and mentioned this, because it forced me to rethink the issue, including refreshing my memory of Oliveira's

O Livro da Fábrica das Naus, ca. 1580. Admittedly, I had already suspected that it might be about three central frames that are not subjected to transformation as applied to all the other frames. In effect, they rather form the so-called “deadflat”, without applying rising and narrowing for those three frames, but now I am more certain of it.

The thing is that the (base) “point” was then called the point lying on the flat of the bottom (in the design sense), and the use of “deadflat” itself is described as normal practice in Portuguese works from that period and, depending on the size of the ship, may include, for example, three or five central frames. This does not make a very notable difference to the shape of the hull, but it does occur and, naturally, must also be taken into account in this project.

As it turns out, Fernandes' patacho design seems to sport a “deadflat” three frames long, covering the master frame and two adjacent frames. In total, there were 33 numbered frames, however, the latter is literally stated in another passage of the text, not yet quoted.

.