another interesting development

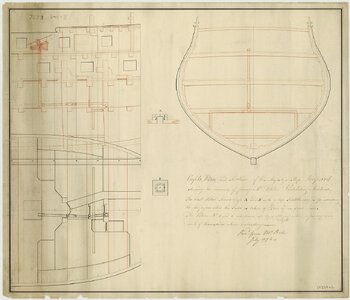

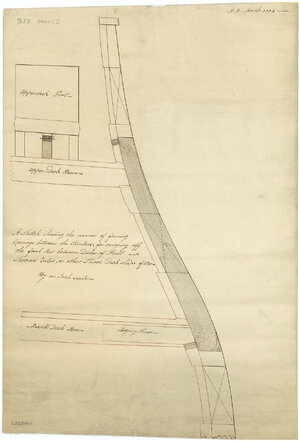

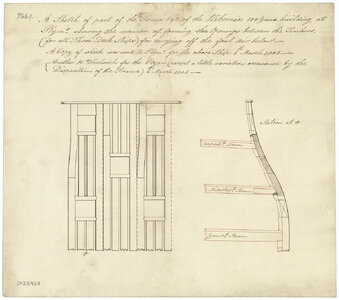

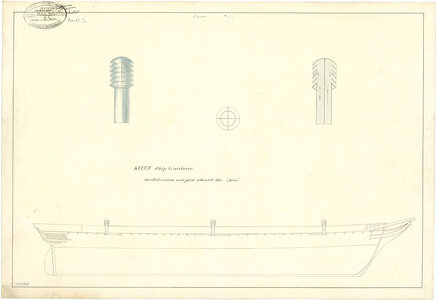

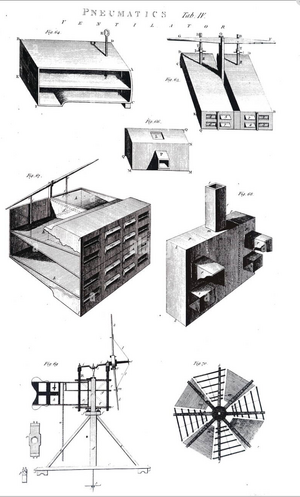

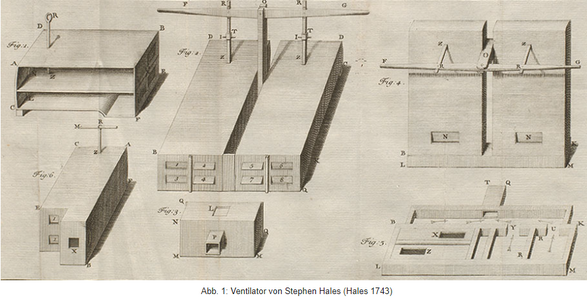

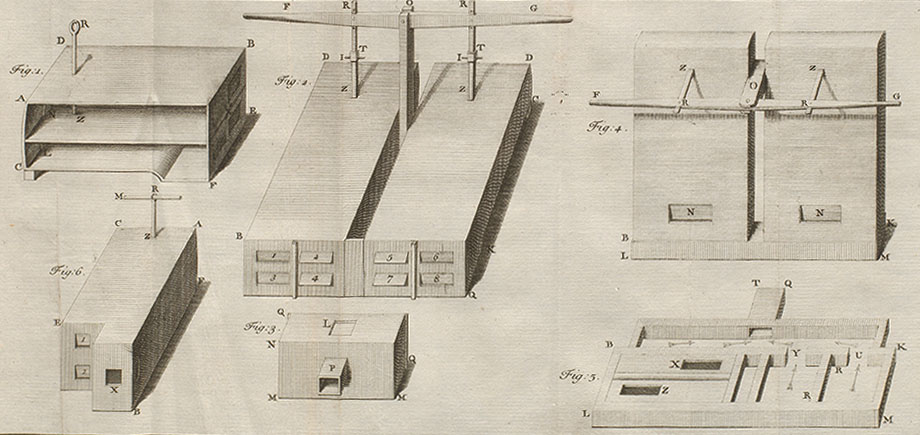

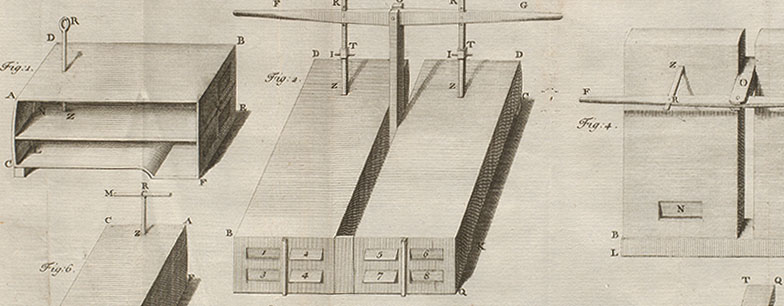

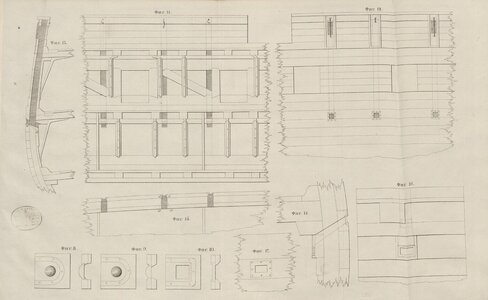

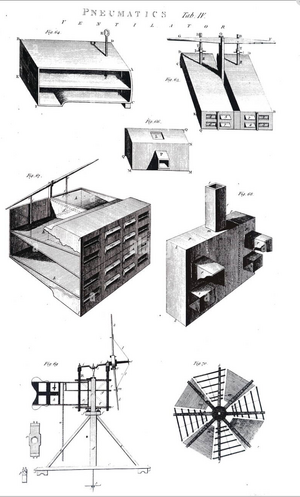

An engraving depicting Stephen Hales' ventilators -

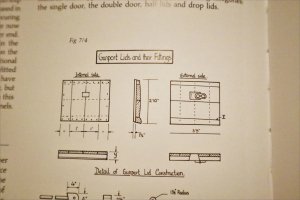

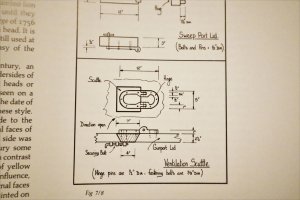

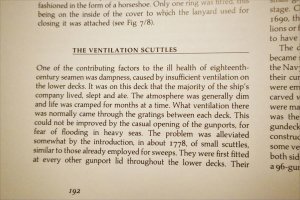

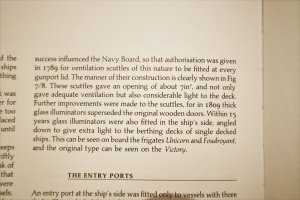

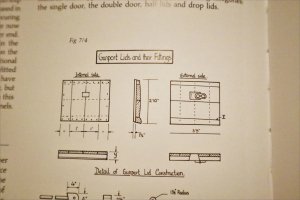

Top: a ship's ventilator as used by the British Navy - complete and sectional views.

Centre: a ventilator used in old Newgate Jail.

Bottom: a windmill which powered the Negate ventilator. Stephen Hales (1677-1761) an English clergyman who made significant contributions to a range of scientific fields including botany, atmospheric chemistry and physiology. Dated 18th century

Captions are provided by our contributors.

translated by google from the orginal german text:

"The ship's lungs": Stephen Hales invention of a fan for ventilating ships and other rooms

April 9, 2021 Edith Völker

The good and regular ventilation of buildings and public transport to prevent the spread of disease became an omnipresent topic again with the emergence of Covid-19. Stephen Hales (1677-1761) published his work A Description of Ventilators in 1743, in which he presented the invention of a fan for ventilating mines, prisons, hospitals, penitentiaries and ships.

Hales dedicated his work to sailors who were confronted with infectious diseases typical of the sea during long sea voyages:

As Sea-farers, that Valuable and Useful Part of Mankind, have many Hardships and Difficulties to contend with, so it is of great Importance to obviate as many of them as possible: And as the noxious Air in Ships has hitherto been one of their greatest Grievances, by making sick and destroying multitudes of them.

Hales 1743, V

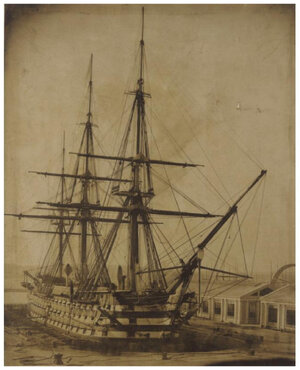

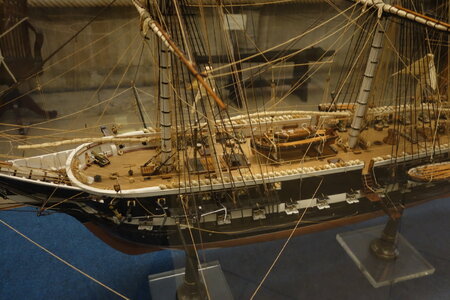

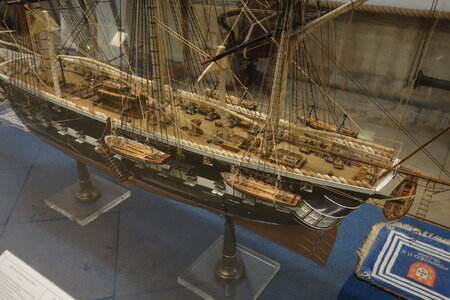

The occurrence of infectious diseases on long sea voyages led to great human and financial losses for merchant and warships in the 18th century. Scientists and doctors increasingly attributed the causes of such diseases to the poor air below deck, even if they were not yet able to provide a relevant explanation for its occurrence. The ships were often overcrowded and the rooms below deck could only be poorly ventilated through a few hatches. In bad weather conditions or high seas, the hatches often had to remain closed. In addition, with the construction of larger ships with multiple decks, this ventilation method became increasingly ineffective (Zuckermann 1976-1977, 228).

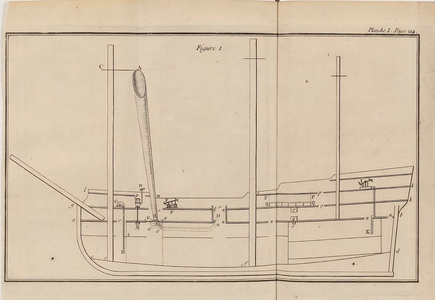

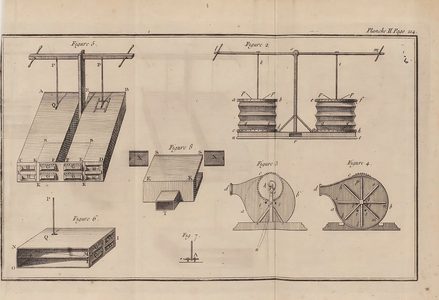

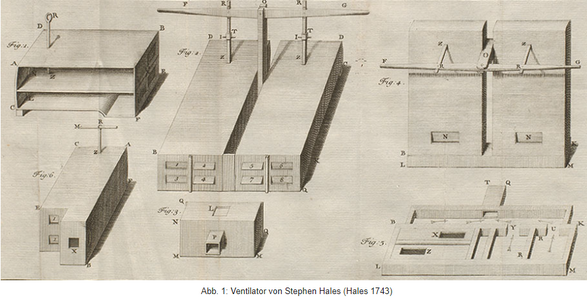

Chemically cleaning the air by burning juniper or sulfur or sprinkling the rooms with vinegar brought little improvement. This prompted Stephen Hales to look for another solution to the problem at about the same time as Samuel Sutton. Stephen Hales described a fan that worked like the bellows of an organ. In two boxes there was a plate that could be moved up and down and created an air stream that could pump air in and out of the rooms below deck via tubes.

Fig. 1: Fan by Stephen Hales (Hales 1743)

The disadvantage of this invention was that the fan took up additional space on the ship - where space was already limited - and had to be regularly kept running by two men.

In 1743, the doctor Richard Mead (1673-1754) recommended the ventilation system developed by Samuel Sutton to the Royal Navy, which did not require direct human labor and required less space. Sutton had observed that a draft was created in enclosed spaces if two of three fireplaces were heated with fire. He developed a ventilation system that worked using a space-saving system of pipes and the fire in the ship's galley. The disadvantage of this design was that it often could not be used in high seas and bad weather because the fire in the galley had to be extinguished (Schadewaldt 1968, 14-15).

Stephen Hale's ventilator was initially used on merchant ships and after it was proven that the good ventilation of the decks meant that far fewer people fell ill on long sea voyages, it was also tested on warships. In 1756, the ventilator was used on the largest ship in the Royal Navy and after 850 people survived the voyage in good health, it was decided to install a ventilator for the entire fleet (Hales 1758, 96-97).

Literature:

Ellis, F. P. (1948): Victuals and Ventilation and the Health and Efficiency of Seamen. British Journal of Industrial Medicine , Oct., 1948, Vol. 5, No. 4 (Oct., 1948), 185-197.

Schadewaldt, H. (1968): On the history of traffic medicine with particular reference to maritime medicine. In: H. Wagner and K. J. Wagner (eds.): Handbook of traffic medicine. Berlin: Springer Verlag.

Zuckermann, A. (1976-1977): Scurvy and the Ventilation of Ships in the Royal Navy: Samuel Sutton’s Contribution. Eighteenth-Century Studies, Winter, 1976-1977, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Winter, 1976-1977), 222-234.

«The ship’s lungs»: Stephen Hales Erfindung eines Ventilators zur Belüftung von Schiffen und anderen Räumen

9. April 2021

Edith Völker

Die gute und regelmässige Belüftung von Gebäuden und öffentlichen Verkehrsmitteln, um die Ausbreitung von Krankheiten zu verhindern, wurde mit dem Auftreten von Covid-19 wieder zu einem allgegenwärtigen Thema. Stephen Hales (1677-1761) veröffentlichte 1743 sein Werk

A Description of Ventilators, in dem er die Erfindung eines Ventilators zur Belüftung von Bergwerken, Gefängnissen, Krankenhäusern, Zuchthäusern und Schiffen vorstellte.

Hales widmete seine Schrift den Seefahrern, die bei langdauernden Seereisen mit seetypischen Infektionskrankheiten konfrontiert waren:

As Sea-farers, that Valuable and Useful Part of Mankind, have many Hardships and Difficulties to contend with, so it is of great Importance to obviate as many of them as possible: And as the noxious Air in Ships has hitherto been one of their greatest Grievances, by making sick and destroying multitudes of them.

Hales 1743, V

Das Auftreten von Infektionskrankheiten auf langen Seereisen führte bei Handels- und Kriegsschiffen im 18. Jahrhundert zu grossen menschlichen und finanziellen Verlusten. Wissenschaftler und Ärzte führten die Ursachen für solche Krankheiten zunehmend auf die schlechte Luft unter Deck zurück, auch wenn sie für deren Auftreten noch keine einschlägige Erklärung erbringen konnten. Die Schiffe waren oft überfüllt und die Räume unter Deck konnten über wenige Luken nur schlecht belüftet werden. Bei schlechten Wetterverhältnissen oder hohem Seegang mussten die Luken häufig geschlossen bleiben. Hinzu kam, dass mit dem Bau von grösseren Schiffen mit mehreren Decks diese Belüftungsmethode zunehmend wirkungslos blieb (Zuckermann 1976-1977, 228).

Eine chemische Reinigung der Luft durch das Verbrennen von Wacholder oder Schwefel oder das Besprengen der Räume mit Essig brachten kaum Besserung. Das veranlasste Stephen Hales etwa zur gleichen Zeit wie Samuel Sutton nach einer weiteren Lösung für das Problem zu suchen. Stephen Hales beschrieb einen Ventilator, der wie ein Blasebalg einer Orgel funktionierte. In zwei Kästen befand sich je eine Platte, die auf und ab bewegt werden konnte und einen Luftstrom erzeugte, mit dem Luft über Röhren aus den Räumen unter Deck heraus- und hineingepumpt werden konnte.

Abb. 1: Ventilator von Stephen Hales (Hales 1743)

Der Nachteil dieser Erfindung war, dass der Ventilator auf dem Schiff – wo der Platz schon an sich begrenzt war – zusätzlichen Raum beanspruchte und regelmässig durch zwei Männer in Gang gehalten werden musste.

Der Arzt Richard Mead (1673-1754) empfahl 1743 der Royal Navy das von Samuel Sutton entwickelte Belüftungssystem, das ohne direkte menschliche Arbeitskraft auskam und weniger Platz erforderte. Sutton hatte beobachtet, dass in geschlossenen Räumen ein Luftzug zustande kam, wenn bei drei Kaminen zwei mit Feuer beheizt wurden. Er entwickelte eine Lüftung, die mittels eines platzsparenden Röhrensystems und dem Feuer in der Schiffskombüse funktionierte. Der Nachteil dieser Konstruktion war, dass sie bei hohem Seegang und schlechtem Wetter oft nicht genutzt werden konnte, weil das Feuer in der Kombüse gelöscht werden musste (Schadewaldt 1968, 14-15).

Stephen Hales Ventilator kam vorerst auf Handelsschiffen zum Einsatz und nachdem sich nachweisen liess, dass durch die gute Belüftung der Decks viel weniger Personen auf langen Seereisen erkrankten, wurde er auch auf Kriegsschiffen getestet. 1756 kam der Ventilator auf dem grössten Schiff der Royal Navy zum Einsatz und nachdem 850 Personen die Reise gesund überstanden, wurde für die ganze Flotte der Einbau eines Ventilators beschlossen (Hales 1758, 96-97).

Literatur:

Ellis, F. P. (1948): Victuals and Ventilation and the Health and Efficiency of Seamen. British Journal of Industrial Medicine , Oct., 1948, Vol. 5, No. 4 (Oct., 1948), 185-197.

Schadewaldt, H. (1968): Zur Geschichte der Verkehrsmedizin unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Schiffahrtsmedizin. In: H. Wagner und K. J. Wagner (Hg.): Handbuch der Verkehrsmedizin. Berlin: Springer Verlag.

Zuckermann, A. (1976-1977): Scurvy and the Ventilation of Ships in the Royal Navy: Samuel Sutton’s Contribution. Eighteenth-Century Studies, Winter, 1976-1977, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Winter, 1976-1977), 222-234.

Die gute und regelmässige Belüftung von Gebäuden und öffentlichen Verkehrsmitteln, um die Ausbreitung von Krankheiten zu verhindern, wurde mit dem Auftreten von

etheritage.ethz.ch