Hello my Friends.

Yesterday, around lunch time, the Admiral asked me if I was not going to work on the ship? My answer was: "Nah, I think we both deserve a rest!

So, apart from mixing the stain, I did absolutely nothing. Today, this same scene played itself out again. The fact is that planking this little ship has quite been quite the challenge, including not only the actual planking, but also engineering the different hull shape and shaping those filler blocks.

Therefore, I thought it would be appropriate to evaluate the hull shape of the WB and give you treater insight as to why I spent such a long time on getting the actual hull shape right. As usual, I am using

@Ab Hoving Ab's "Het Schip van Willem Barents" as the main source of information:

DETERMINING AND EVALUATING THE HULL SHAPE OF THE WILLEM BARENTSZ

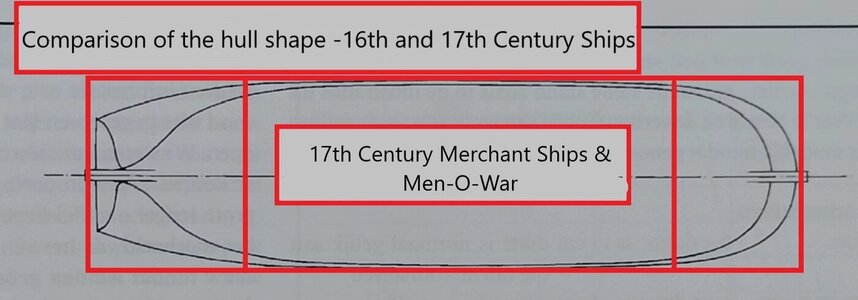

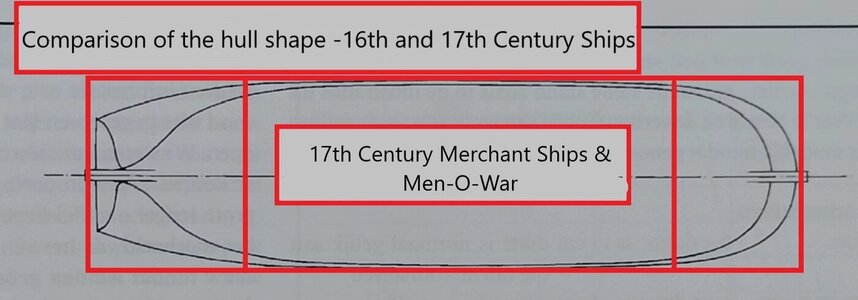

When examining the books of Witsen (1670) en Van Yk (1697), which describe shipbuilding from 1625 onwards, we notice that the widest point of ships’ hulls occurred at a point which was approximately one third from the bow. Viewed from above, ships of this period – whether they were merchant ships or men-o-war - had an almost rectangular shape. In other words, when the width of the front bulkhead of the frame is viewed in relation to the width of the bulkhead behind the large mast, (two parts that are often easy to distinguish on images and can therefore be compared), there would be a very small difference. The conclusion was that ships’ hulls of this time would only start their taper (the loss of width forwards and backwards) at the very last minute.

Note the rectangular shape of hulls from 1625 onwards and the fact that the taper of the hull occurred only at the ends. Therefore, you will see that whether you are building a 17th Century British, Dutch, French or Swedish (yes, we can never forget about our contingent of VASA builders

) ship, they all look essentially the same when viewed from the top.

The reason why the full hull shape was chosen for merchant ships, is obvious. Shipowners were primarily looking for load capacity, while speed, despite the perishability of the goods transported, was not considered as important. Less understandable is that the full hull shape was also preferred for men-o-war – especially when speed and maneuverability could be considered as important aspects. Here we have to take into account though, that the difference between merchant-and warships was so small in the first half of the 17th century that the extra carrying capacity – which also meant extra guns – were deemed more important than speed.

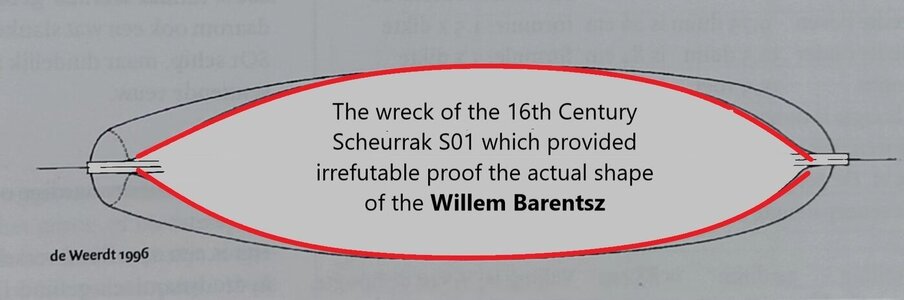

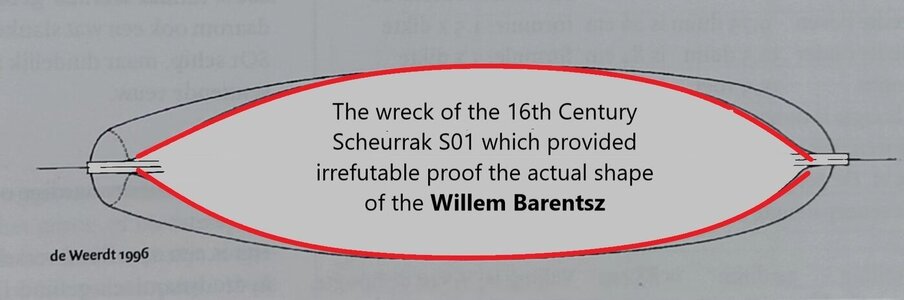

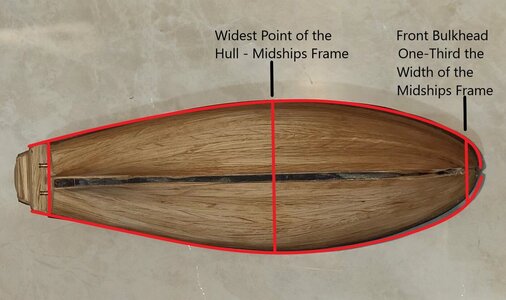

However, if we examine the wreck of the Scheurrak S01 (circa 1590s – the same time frame as the Willem Barentsz), we see a ship of which the front bulkhead is perhaps half the width of the widest frame midships. Compared to other drawings and paintings of the time, we see the exact same thing – ships from this earlier period do not appear rectangular, but almost elliptically-shaped when viewed from above. In other words: the greatest width did not occur a third from the front of the hull, but midships.

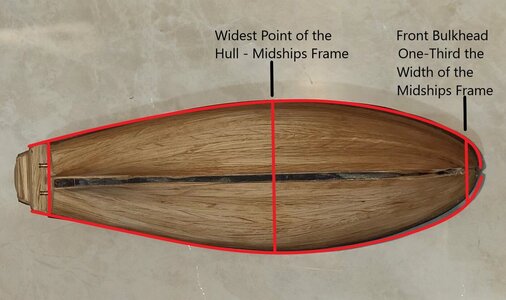

In contrast to the full hull shape, the elliptical hull of the Willem Barentsz would have resulted in greater speed and maneuverability – two aspects which would both have been regarded as highly desirable for a ship to be used for polar exploration. Load capacity was very much of secondary importance. Here you can clearly see that the widest part of the hull occurs at the midships point while the width of the bow and stern bulkheads are roughly a third from the widest one at the midships point.

Just look at the elliptical (and in the eyes of this beholder) beautiful hull shape of the Willem Barentsz, which conforms 100% to the ethos of 16th Century Dutch design. That is why it was critical to me to get the hull shape as accurate as I could - it is, after all, one of the most distinguishing features of the ship.

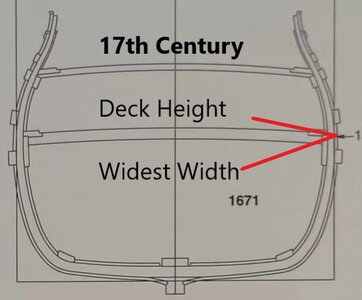

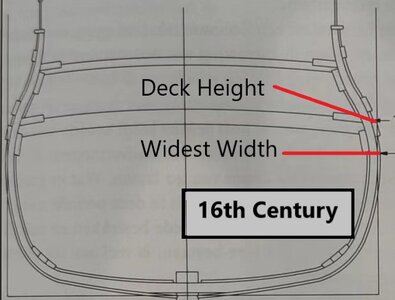

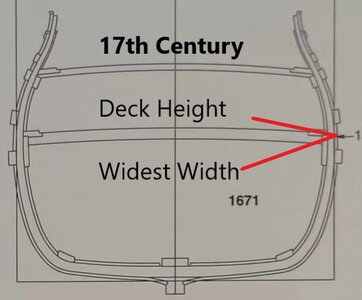

There is a second aspect that is very important: from Witsen and from Yk's writings and drawings, it appears that the greatest width of the individual bulkhead for ships of their time coincided with the height of the deck height. Witsen calls this spot which was used by shipwrights to determine the hull shape, “uitwatering”. “Uitwatering” translated into English means “drainage” – which I interpret as the line along the hull where the scuppers would be located.

The bulkhead of a Dutch ship (circa 1671) which shows that the widest point of the frame coincides exactly with the deck level.

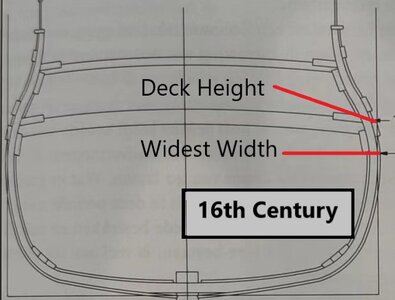

In contrast to the ships of the Witsen and Van Yk’s eras, ships of the sixteenth century – of which the Willem Barentsz was one – displayed a different characteristic: the widest part of the individual bulkhead did not occur at deck level but below deck level. Taking into account the Dutch building method of shell- first, this would result in a drastic difference in hull shape between ships of the two eras. So, what effect would this have? In a nutshell, the lower point at which uitwatering occurred, would result in a lower center of gravity which, in turn, would result in greater stability of the ship.

The frame of a 16th Century Dutch ship (read Willem Barentsz) shows that the widest point of the individual frame occurs well BELOW deck level resulting in a lower Center of Gravity and increased stability.

In an earlier section where I discussed how the size of the WB was determined, I did touch upon its sailing characteristics, but it is worth repeating. The WB could travel under full-sail up to a to a wind strength of 5 as measured on the Scale of Beauford. In stronger wind conditions, the sail area would have to be reduced.

The maximum speed under full sail is calculated as 8 knots*. The total water displacement is calculated at 120 tonnes (60 lasten). With a load capacity of 30 last (60 tonnes) as described by De Veer in his diaries, it would allow 60 tonnes for the actual weight of the ship and its equipment. This meant that the WB would be a very well-balanced ship with superior speed and maneuverability (read sailing characteristics) than her 17th Century counterparts!

*The speed of 8 knots compared very favorably to the approximate 5 knots of the 17th Century merchantmen and men-o-war.

Keeping the above in mind, the time spent in determining the exact hull shape, preparing for planking and the planking itself was well warranted!

osmocolorusa.com