Hello Dear Friends

Some time ago, when

@Kolderstok Hans replied to the ongoing debate about whether both lifeboats or only one was stored on deck, he referred to an ancient Dutch publication “Sinnepoppen” by Roemer Visscher. Imagine my absolute surprise and delight when

@Frank48 Frank sent me this publication in PDF format. Thank you Frank!

Why was I delighted? Because this book - even though it is completely unrelated to historical Dutch shipbuilding and naval archaeology - can be used to throw light on the whole lifeboat issue.

First though, I have to explain the genre of the book and why the book type was instrumental in providing the relevant guidance. The really important parts are marked in bold.

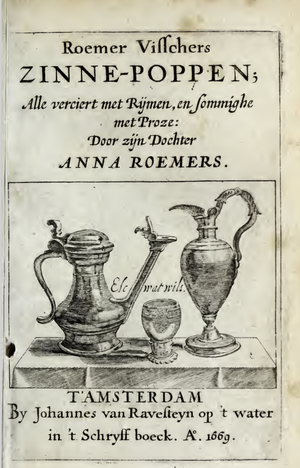

View attachment 304410

This is the title page of the original 1614 edition. The words "Elck wat wils" was Roemer Visscher's personal motto and means "Something for everyone".

View attachment 304411

This is the title page of the 1669 edition and is the edition that

@Frank48 Frank sent me.

Sinnepoppen, first published in 1614, is perhaps the most popular

emblem book of the Dutch Golden Age. Emblems were generally made up of three components: a title or motto (referred to by the Latin term inscriptio), an illustration (pictura) and an explanatory text in prose or, more often, in verse

(subscriptio

). True to the Renaissance-period, myths and legends from ancient Greek and Roman literature and Biblical and Christian motifs influenced the emblem genre in a significant way.

The emblematic book

referred directly to daily life, resulting in highly recognizable and therefore extremely popular emblem books.

These emblems were the perfect vehicle for moralistic lessons, as can be observed in Roemer Visscher`s Sinnepoppen.

The emblematic book as genre

was introduced to the Low Countries (Netherlands) in the 1550s and by the 1570s an increasing number of poets wrote in this vernacular. In 1601, Daniel Heinsius published the first emblem book with subscriptions in Dutch, and other prominent poets such as Hooft, Vondel and Roemer Visscher soon followed his example. Nowhere else was the genre to flourish as richly as in the (Northern) Netherlands.

The work contains 183 emblems, divided into three sections, so-called 'schocken'. The word 'schock', meaning 'a set of sixty', refers to the number of emblems in each part of the book.

View attachment 304412

The first Schock.

Initially Visscher only wanted to publish the picturae. Only after the requests of his dearest friends and the commands ("gebeden en geboden") of the publisher Willem Iansz., did Roemer Visscher eventually decide to add short explanatory subscriptions in prose. Still, he asked his readers to pay more attention to the images, made by the unrelated artist Claes Jansz. Visscher.

As such he was a true believer in "a picture paints a thousand words". And herein lies an important clue.

The pictures that he had chosen to convey a certain moral lesson, had to be one that was extremely well-known by all and which had to be generally accepted as the truth - in other words, it had to be common knowledge. And with that as background, look at the picture that he chose.

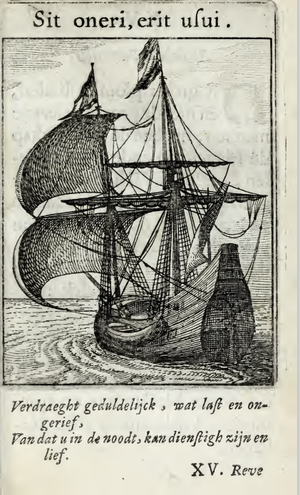

View attachment 304414

The Latin text (the inscriptio) above the picture reads “Sit oneri erit usui” which translates into Dutch as "moge tot last zijn, het zal van nut zijn.” and into English as:

“it may be a burden now, but it will be of use.”

So if we now examine the picture (pictura), we see a lifeboat suspended from the side of a Dutch oceangoing vessel. (We know it is a Dutch vessel because of the Dutch Tricolor flags which are clearly depicted). What is important though is that the picture does not indicate a way of transporting the lifeboat, because that would not have been a "burden". No -

the word "burden" indicates that he is referring to the process of hoisting the lifeboat onboard the ship, which would have been a burden.

The short verse at the bottom of the picture concludes this page. In Dutch it reads:

"Vedraeght geduldelijck, wat last en ongerief, Van Dat u in de noodt, kan dienstigh zijn an lief.

Translated into English, it reads:

Patiently endure the burden and discomfort; when you need it, it will be useful and kind to you.

The prose part of the emblem is as follows:

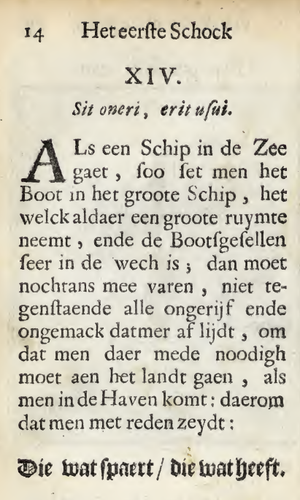

View attachment 304415

In Dutch:

Als een Schip in de Zee gaet, soo set men het Boot (NOT THE SLOOP!!!) in het groote Schip, het welckaldaer een groote ruymte neemt, ende de Bootgesellen seer in de wech is; dan moet nochtans mee varen, niet tegenstaende alle ongerijf ende ongemaeck datmer af lijdt, om dat men daer mede noodigh moet aen het landt gaen, als men in de Haven komt: daerom dat men met reden zeydt:

Die wat spaert / die wat heest.

In English:

If a ship goes out to sea, the boat is put onboard the big ship where it takes up a lot of space and is in the way of the crew. Despite all the inconvenience and discomfort, they may suffer, the crew has to accept this, because they have to go to land in it when they reach the harbour. That is why he who saves, has.”

Therefore dear friends, like

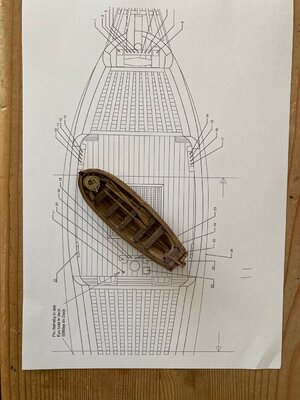

@Kolderstok Hans concluded in his posting, it was vitally important to have both boats onboard – in an emergency, it could mean the difference between life and death.

Thank you so much Hans for pointing me in the right direction, and thank you Frank for the book. Slowly, but surely my Willem Barentsz puzzle is falling into place.

I love it Hans! You are right - I was stuck indeed, but no longer. To me things are starting to make sense; now it's just a case of putting it into practice! And like you have suggested in your picture (thank you very much for that!) who is to say that the boat wasn't stored like that or in another configuration. Like you say, now there is all of a sudden a lot of space.

I love it Hans! You are right - I was stuck indeed, but no longer. To me things are starting to make sense; now it's just a case of putting it into practice! And like you have suggested in your picture (thank you very much for that!) who is to say that the boat wasn't stored like that or in another configuration. Like you say, now there is all of a sudden a lot of space.