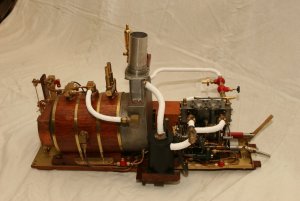

A log of the build of an 1800mm (6 feet) steam launch

‘Natterer’ – A shipbuilding Odyssey?

In 1977 I set out to build a steam launch. In 2010 I finally finished it.

So what had I accomplished in the intervening 33 years? Well, quite a lot – I learnt how to machine metal; how to draught a boat’s lines; how to build a wooden hull; how to install a steam plant and fairly simple electronics; and how to stop bleeding and apply sticking plasters.

I had written a partial write-up many years ago, to put in my club newsletter (circulation at least ten people – a very small club, but beautifully formed), so I’ve used this as the starting point, and added further sections and photos to suit.

Hope you like it! I’ll post a couple of photos now, then add more text as we go along

‘Natterer’ – A shipbuilding Odyssey?

Ann, the better third, made a serious error of judgement in 1977 to compound the one she had made in 1974 when she married me. Despite all the warning signals that she had seen in three years of marriage, she failed to recognise she had a fanatical modeller on her hands, and asked me what I wanted for Christmas.

Well this was too good an opportunity to miss, and it germinated the seed of an idea I had been toying with for years- I wanted to build a steam launch! So she gulped, looked at our finances, and bought me a Unimat SL lathe.

As luck would have it, that year we had a holiday in the Cotswolds, and wouldn’t Henley-on-Thames be a nice place to visit, and look! - there might be an interesting shop over there, down that little alley we can’t quite see from here, but if we go over the road……?

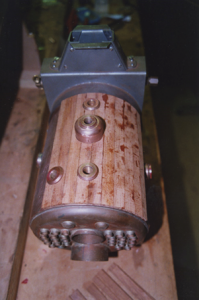

Yes, Stuart Turner Ltd still had their premises there in 1977, before they decamped for the Channel Isles, and before the day was out I was the proud possessor of a set of castings for a Stuart Launch engine, and Ann was £19.80 lighter in pocket with a suspicion she had been out-manoeuvred. (Incidentally, that same set of castings would now cost £282 !)

Now the brighter ones amongst you will have twigged that there appears to be an element of cart before horse here, as no mention has been made of a boat to put said engine in. That’s right, Ted had got it xxxx about face, and hadn’t got a clue as to what sort or size of boat he would eventually build!

That didn’t matter really, as I considered that the heart of the project was the engine, and that a suitable hull would crop up eventually.

So off to the engine, and the realisation that I was going to have to learn a lot of new techniques in order to machine a relatively large engine on a lathe that was basically tiny. First rule of learning - start on a simple part, where it wouldn’t matter if I ruined it - so what do I start with? - That’s right - The cylinder block!

No, I’m pleased to say I didn’t ruin it, but the lathe was very hard pressed to accept such a block of cast iron, and I had to resort to machining surfaces true, but to nominal dimensions, and make matching parts to suit.

It soon became apparent, as my skills improved, that there was no way I was going to be able to mount the cylinder block on the lathe in order to machine the cylinder bores (two of them, each 1” bore and stroke) as there just wasn’t enough swing over the bedplate, and I didn’t have a boring bar.

Fortunately, my neighbour was a shop floor manager with a machine company manufacturing high speed looms, and he came to the rescue.

‘What tolerance do you want it bored to, Ted’

-‘Er, it doesn’t really matter, Robbie, as I’ll just turn the pistons to suit’

The silence that ensued spoke volumes as 30 years of machining experience looked down his nose at the unpleasant smell of 30 days bodging.

‘I’ll give it to one of my apprentices then, as a training exercise’

Three days later, the cylinder block returned, with the pointed observation that it had been turned to 1”, with a tolerance of + .0001” – that’s right – a tenth of a thou! I took him at his word.

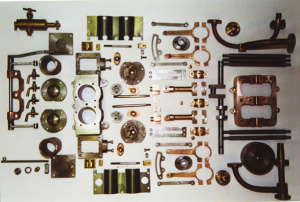

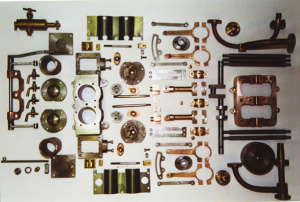

After this, machining proceeded briskly, with bedplate, journals, columns fairly flowing off the lathe.

I learnt how to drill and tap; what to do when the tap broke in the hole (Throw away and start again - luckily it was a small part!) and I even learnt how to silver solder and put out the ensuing conflagration.

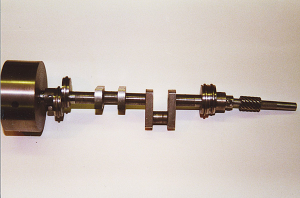

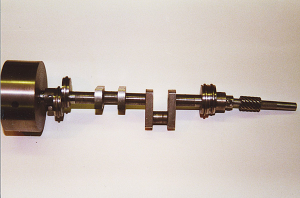

But all this time, I was aware that the real test of my new found skills was fast looming on the horizon - the crankshaft.

The crankshaft was a single casting, with two cranks at 90 degrees. It would just fit on the lathe, and I was able to machine the three main bearings with no real problems. The fun began with the machining of the offset cranks. Luckily, I had picked up a book in my travels which suggested the solution, and I obtained a 2” length of 2” diameter brass round, into which I drilled an offset hole the diameter of the crank. The hole was drilled offset by the throw of the crank, and two short dowels were set into the end of the round. This enabled me to clamp the end of the crank into the round, secured by two grubscrews, with the dowels securely locating the crank web such that the crank journal (The big-end) was now firmly held on the centreline of the lathe. Bingo! - the big ends could now be turned!

After that little triumph, mere bagatelles such as double eccentrics and Stephenson reversing links held no fears for me, and the engine rapidly came together. It even looked vaguely like the picture on the box! The engine was assembled with the exception of the connecting rods and pistons, when fate dealt a hand, and we decided the time had come to move house.

The new house was 120 years old and looked it - major work was required. The engine was wrapped up and put away for the duration - it was to be seven long years before the project once again surfaced.

‘Natterer’ – A shipbuilding Odyssey? – Part 2

‘Why do we need to move? What’s wrong with this house? We can’t afford it! Give me one good reason why we should move! - (Series of dull thuds, reminiscent of heavy objects meeting flesh) - Alright, we’ll move, but please stop!’

We found a house, with an acre of ground (Vehicle storage said Ted, Goats said Ann), and a proper walk-in room in the roof (Bedroom said Ann, Workshop said Ted). The goats duly arrived, but the amount of work required on the house meant the workshop/bedroom remained as a store-room, and no modelling took place for seven long years.

During this time however, we discovered that Mecca for steam boat enthusiasts, namely the Windermere Steamboat Museum. What a feast of delights! Steamboats of all shapes and sizes wherever you looked! The graceful lines of the Victorian launches, the colours of the timbers and above all the sight and sound of operating steam engines took our breath away. We were particularly attracted to “DOLLY”, the oldest working steamboat in the world, which had spent some eighty years on a lake bed after being nipped in the ice.

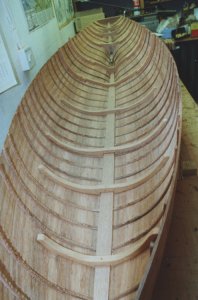

I approached the museum, and was readily given permission to spend a couple of days measuring her up and taking numerous photographs. They even had a small-scale set of lines available! Once home, I set to with slide-rule and drawing board and converted those lines into a working set of drawings. This was where the problems started! You will remember that in the last episode I admitted I was doing things backside foremost, and had started with the engine! Now said engine was quite big (and heavy) and clearly wasn’t going to like being shoe-horned into a two-foot hull. In fact, when I had finished all the measuring and scaling the hull ended up at about 72 inches ( 1830 mm to the youngsters)

Alright, so it was going to be a big boat! That wasn’t a problem in itself, as I had always wanted a big hull, but the problems arose when I worked out that the model’s calculated displacement to waterline was about 5 lbs less than the all-up weight would be! Calculations also revealed that the metacentric height was going to be in the region of 3/8 of an inch, which when combined with the nearly hemispherical mid-ships section meant she was going to be rather tender and roll like a pig in mud. (or similar – substitute as you see fit)

The solution was to subtly rework the sections to give a greater displacement, with additional buoyancy being placed in the quarter buttocks, so as to increase the metacentric height, and reduce the roll rate. On paper, it would work, but the weight of the hull and engine plant would be critical, with no room for error. The only other solution would have been to increase the hull length to seven feet, but that was starting to be ridiculous!

On with the motley! – Have you ever tried to produce drawings for a 72” hull on a 40” drawing board? – Difficult. As I started to scale up the museum’s lines drawing, it became apparent that all was not well, and that the drawing was highly suspect. A good excuse for a further trip, and a days’ measuring. Back home, and I was able to translate the new information onto the drawings and fair the lines up properly. Incidentally, if you are ever having to prepare a set of drawings, remember a hull is three-dimensional, and cannot be adequately defined with just a profile and sections on a two dimensional drawing – it is essential to add both futtock and buttock lines to the drawing. The profile, sections and buttocks may appear to give a true form, but attempting to fair in the futtocks will soon highlight any discrepancies.

The final drawings were prepared at work on an eight foot table, where I coerced all the members of my drainage design team into holding down a six foot spline as I inked in the lines!

It was 1988, only eleven years after the start of this tale, and at last! I had a set of working drawings! At last I had a stock of well seasoned lime! At last I had an engine! At last I...........don’t think I like the boat any more, said Ann.

‘Natterer’ – A shipbuilding Odyssey?

In 1977 I set out to build a steam launch. In 2010 I finally finished it.

So what had I accomplished in the intervening 33 years? Well, quite a lot – I learnt how to machine metal; how to draught a boat’s lines; how to build a wooden hull; how to install a steam plant and fairly simple electronics; and how to stop bleeding and apply sticking plasters.

I had written a partial write-up many years ago, to put in my club newsletter (circulation at least ten people – a very small club, but beautifully formed), so I’ve used this as the starting point, and added further sections and photos to suit.

Hope you like it! I’ll post a couple of photos now, then add more text as we go along

‘Natterer’ – A shipbuilding Odyssey?

Ann, the better third, made a serious error of judgement in 1977 to compound the one she had made in 1974 when she married me. Despite all the warning signals that she had seen in three years of marriage, she failed to recognise she had a fanatical modeller on her hands, and asked me what I wanted for Christmas.

Well this was too good an opportunity to miss, and it germinated the seed of an idea I had been toying with for years- I wanted to build a steam launch! So she gulped, looked at our finances, and bought me a Unimat SL lathe.

As luck would have it, that year we had a holiday in the Cotswolds, and wouldn’t Henley-on-Thames be a nice place to visit, and look! - there might be an interesting shop over there, down that little alley we can’t quite see from here, but if we go over the road……?

Yes, Stuart Turner Ltd still had their premises there in 1977, before they decamped for the Channel Isles, and before the day was out I was the proud possessor of a set of castings for a Stuart Launch engine, and Ann was £19.80 lighter in pocket with a suspicion she had been out-manoeuvred. (Incidentally, that same set of castings would now cost £282 !)

Now the brighter ones amongst you will have twigged that there appears to be an element of cart before horse here, as no mention has been made of a boat to put said engine in. That’s right, Ted had got it xxxx about face, and hadn’t got a clue as to what sort or size of boat he would eventually build!

That didn’t matter really, as I considered that the heart of the project was the engine, and that a suitable hull would crop up eventually.

So off to the engine, and the realisation that I was going to have to learn a lot of new techniques in order to machine a relatively large engine on a lathe that was basically tiny. First rule of learning - start on a simple part, where it wouldn’t matter if I ruined it - so what do I start with? - That’s right - The cylinder block!

No, I’m pleased to say I didn’t ruin it, but the lathe was very hard pressed to accept such a block of cast iron, and I had to resort to machining surfaces true, but to nominal dimensions, and make matching parts to suit.

It soon became apparent, as my skills improved, that there was no way I was going to be able to mount the cylinder block on the lathe in order to machine the cylinder bores (two of them, each 1” bore and stroke) as there just wasn’t enough swing over the bedplate, and I didn’t have a boring bar.

Fortunately, my neighbour was a shop floor manager with a machine company manufacturing high speed looms, and he came to the rescue.

‘What tolerance do you want it bored to, Ted’

-‘Er, it doesn’t really matter, Robbie, as I’ll just turn the pistons to suit’

The silence that ensued spoke volumes as 30 years of machining experience looked down his nose at the unpleasant smell of 30 days bodging.

‘I’ll give it to one of my apprentices then, as a training exercise’

Three days later, the cylinder block returned, with the pointed observation that it had been turned to 1”, with a tolerance of + .0001” – that’s right – a tenth of a thou! I took him at his word.

After this, machining proceeded briskly, with bedplate, journals, columns fairly flowing off the lathe.

I learnt how to drill and tap; what to do when the tap broke in the hole (Throw away and start again - luckily it was a small part!) and I even learnt how to silver solder and put out the ensuing conflagration.

But all this time, I was aware that the real test of my new found skills was fast looming on the horizon - the crankshaft.

The crankshaft was a single casting, with two cranks at 90 degrees. It would just fit on the lathe, and I was able to machine the three main bearings with no real problems. The fun began with the machining of the offset cranks. Luckily, I had picked up a book in my travels which suggested the solution, and I obtained a 2” length of 2” diameter brass round, into which I drilled an offset hole the diameter of the crank. The hole was drilled offset by the throw of the crank, and two short dowels were set into the end of the round. This enabled me to clamp the end of the crank into the round, secured by two grubscrews, with the dowels securely locating the crank web such that the crank journal (The big-end) was now firmly held on the centreline of the lathe. Bingo! - the big ends could now be turned!

After that little triumph, mere bagatelles such as double eccentrics and Stephenson reversing links held no fears for me, and the engine rapidly came together. It even looked vaguely like the picture on the box! The engine was assembled with the exception of the connecting rods and pistons, when fate dealt a hand, and we decided the time had come to move house.

The new house was 120 years old and looked it - major work was required. The engine was wrapped up and put away for the duration - it was to be seven long years before the project once again surfaced.

‘Natterer’ – A shipbuilding Odyssey? – Part 2

‘Why do we need to move? What’s wrong with this house? We can’t afford it! Give me one good reason why we should move! - (Series of dull thuds, reminiscent of heavy objects meeting flesh) - Alright, we’ll move, but please stop!’

We found a house, with an acre of ground (Vehicle storage said Ted, Goats said Ann), and a proper walk-in room in the roof (Bedroom said Ann, Workshop said Ted). The goats duly arrived, but the amount of work required on the house meant the workshop/bedroom remained as a store-room, and no modelling took place for seven long years.

During this time however, we discovered that Mecca for steam boat enthusiasts, namely the Windermere Steamboat Museum. What a feast of delights! Steamboats of all shapes and sizes wherever you looked! The graceful lines of the Victorian launches, the colours of the timbers and above all the sight and sound of operating steam engines took our breath away. We were particularly attracted to “DOLLY”, the oldest working steamboat in the world, which had spent some eighty years on a lake bed after being nipped in the ice.

I approached the museum, and was readily given permission to spend a couple of days measuring her up and taking numerous photographs. They even had a small-scale set of lines available! Once home, I set to with slide-rule and drawing board and converted those lines into a working set of drawings. This was where the problems started! You will remember that in the last episode I admitted I was doing things backside foremost, and had started with the engine! Now said engine was quite big (and heavy) and clearly wasn’t going to like being shoe-horned into a two-foot hull. In fact, when I had finished all the measuring and scaling the hull ended up at about 72 inches ( 1830 mm to the youngsters)

Alright, so it was going to be a big boat! That wasn’t a problem in itself, as I had always wanted a big hull, but the problems arose when I worked out that the model’s calculated displacement to waterline was about 5 lbs less than the all-up weight would be! Calculations also revealed that the metacentric height was going to be in the region of 3/8 of an inch, which when combined with the nearly hemispherical mid-ships section meant she was going to be rather tender and roll like a pig in mud. (or similar – substitute as you see fit)

The solution was to subtly rework the sections to give a greater displacement, with additional buoyancy being placed in the quarter buttocks, so as to increase the metacentric height, and reduce the roll rate. On paper, it would work, but the weight of the hull and engine plant would be critical, with no room for error. The only other solution would have been to increase the hull length to seven feet, but that was starting to be ridiculous!

On with the motley! – Have you ever tried to produce drawings for a 72” hull on a 40” drawing board? – Difficult. As I started to scale up the museum’s lines drawing, it became apparent that all was not well, and that the drawing was highly suspect. A good excuse for a further trip, and a days’ measuring. Back home, and I was able to translate the new information onto the drawings and fair the lines up properly. Incidentally, if you are ever having to prepare a set of drawings, remember a hull is three-dimensional, and cannot be adequately defined with just a profile and sections on a two dimensional drawing – it is essential to add both futtock and buttock lines to the drawing. The profile, sections and buttocks may appear to give a true form, but attempting to fair in the futtocks will soon highlight any discrepancies.

The final drawings were prepared at work on an eight foot table, where I coerced all the members of my drainage design team into holding down a six foot spline as I inked in the lines!

It was 1988, only eleven years after the start of this tale, and at last! I had a set of working drawings! At last I had a stock of well seasoned lime! At last I had an engine! At last I...........don’t think I like the boat any more, said Ann.

Attachments

Last edited by a moderator: