bit by bit the story is weaved together

ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL RESEARCH

The sunken relics of the War of 1812 were not lost to local memory; fascination with the

War of 1812 preserved oral histories of the conflict into the 20th century. Anniversaries

of particular battles and a rebirth of interest in the 1920s and 1930s led to the relocation

and recovery of some vessels.242 In 1927, the wreck of H.M. Schooner

Nancy was

recovered and put on display in Wasaga Beach, Ontario. Four vessels were rumored to

be located in Penetanguishene harbor; locals claimed that the hulls of

Confiance and

Surprize were sunk at the west side of the harbor while another two wrecks, thought to

be

Newash and

Tecumseth, could be found near Magazine Island.

in 1933 the town of Penetanguishene sponsored a recovery in which salvers “floated the

wreck which we had seen in Colborne Basin [part of Penetanguishene harbor] across the

harbor to the town dock and placed its picked bones in the town park.”243 Local

historians suspected that the wreck was the American-built schooner

Scorpion, a

participant in the Battle of Lake Erie that was captured by the British in 1814 and

renamed

Confiance. The wooden remains attracted visitors and vandals alike, and over

time, the hull was pillaged: “much of it…disappeared, being transformed into chairs,

desks, gavels, walking canes, candlesticks, picture frames and other ‘souvenirs of the

Scorpion’.”244 In fact, the wreck pillaged by souvenir hunters was too small to be

Scorpion. Historian C.H.J. Snider later identified it as

Scorpion’s smaller counterpart,

the American-built

Tigress,245 also captured by the British in 1814 and re-named

Surprize.

The 1953 Salvage of Tecumseth

The allure of the War of 1812 continued in the decades following the recoveries of

Nancy and

Tigress. In 1953, Professor Wilfrid W. Jury and students from the University

of Western Ontario began an archaeological project on the grounds of the former naval

establishment at Penetanguishene. Their survey was a success, mapping 30 buildings

and entertaining 17000 tourists.246

Jury and his students included the vessels from Penetanguishene harbor in their plans as

well. The scant remains of

Surprize, ex-

Tigress, were hauled onto the grounds of the old

establishment. That spring, it was announced that the hull of

Scorpion would be

recovered, and Jury made preparations for a salvage attempt. He secured the services of

a dredge and crew for one day in late August, and the town prepared for the reemergence

of the old schooner. An obvious hindrance to the efforts appeared almost

immediately: no one had told Jury exactly where the wreck was located. Many of the

individuals who had been involved in the recovery of

Tigress twenty years earlier had

passed away since those efforts. Nevertheless, Jury proceeded, determined to raise one

of the two wrecks near Magazine Island. At 7:30 a.m. on 29 August 1953, the last day

the dredge was available, “Operation

Scorpion”247 began:

Surrounded by an armada of small craft armed with cameras, flashlights,

microphones and equipment for speech-making and broadcasting, the dredge

plunged its steel-toothed clamshell bucket into a buoyed area a hundred yards

[91.46 m] from the bank, where the water was 15 feet [4.57 m] deep. A pause

while the steel teeth crunched like fangs on a bone, and up rose the bucket,

spewing jets of water, with a tapered black timber in its jaws. Motor horns

among the growing gallery of automobiles and spectators lining the foreshore

‘sounded a peal of warlike glee’ as the derrick arm swung and the opening

bucket dropped the timber on the dredge’s deck. Next was brought up a shorter

mass of blackened oak, with a stout chain attached. This the ‘experts,’ pale

augurs muttering low, pronounced a shank-painter, and none gainsaid their word

– not even when murmuring, ‘

Newash or

Tecumseth,’ they diagnosed the next lot

of oak and ironwork as the port forechains, waterways and channel. The pile of

dripping wood and rusted iron grew on the dredge deck until both bows of the

wreck had been demolished piecemeal, and the water was opaque with disturbed

silt. Still the ship had not been budged.248

Jury and his crew worked late into the evening, until the remains were wrenched from

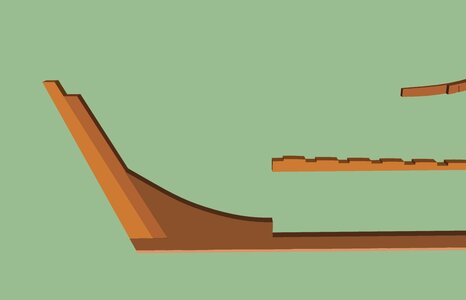

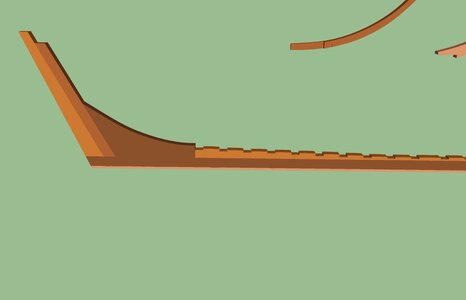

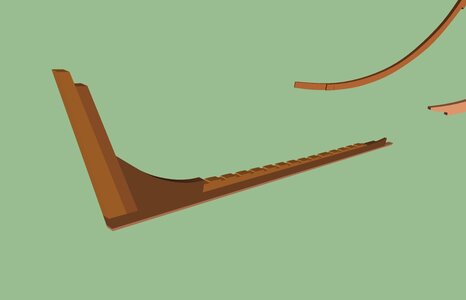

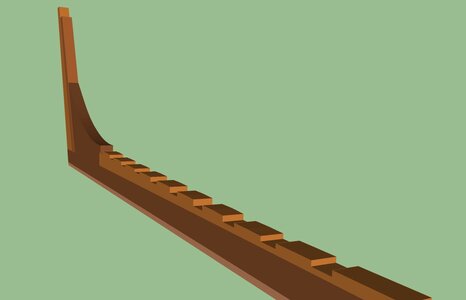

their grave and hauled onshore (fig. 14). Several timbers had been dislodged from their

original places on the hull. Twelve round shot were found, cleaned, and emblazoned

with the name “

Scorpion.”249 The wreck was examined by a number of experts250 who

all reached the same conclusion. The wreck was certainly not

Scorpion; it was too large.

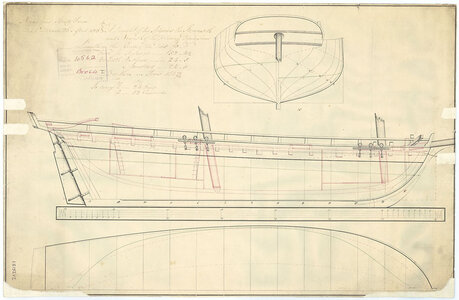

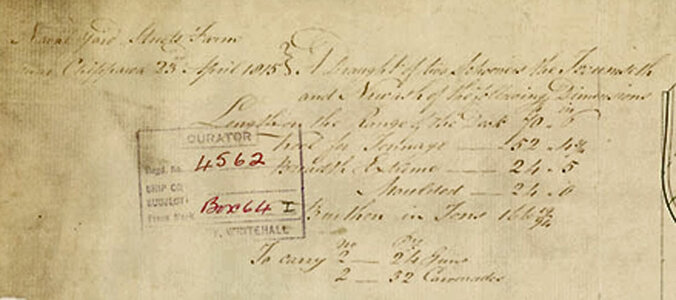

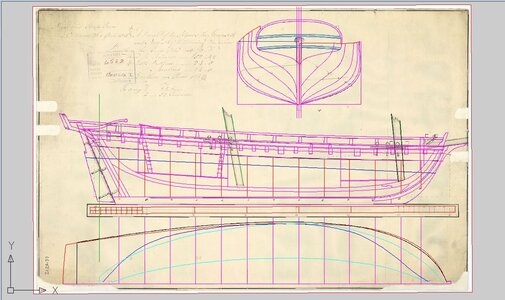

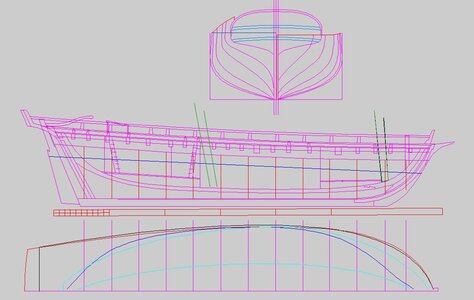

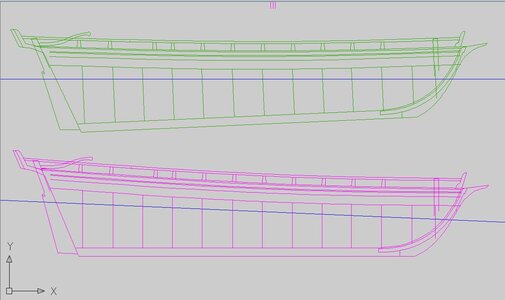

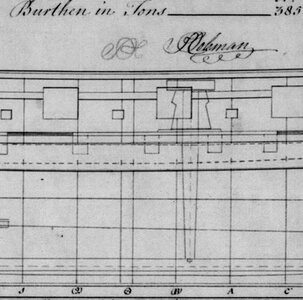

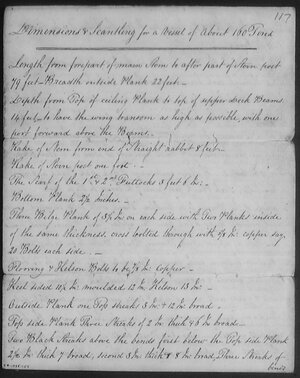

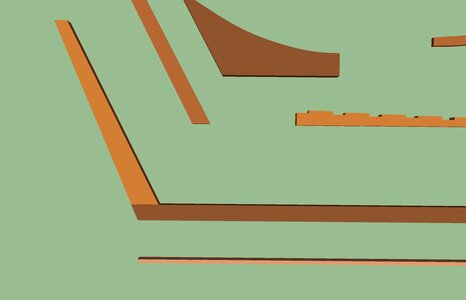

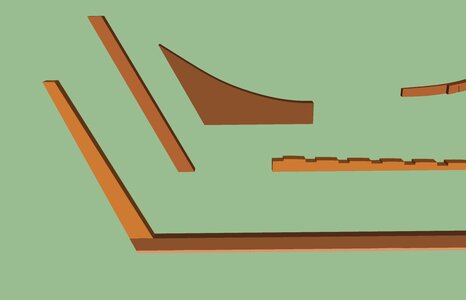

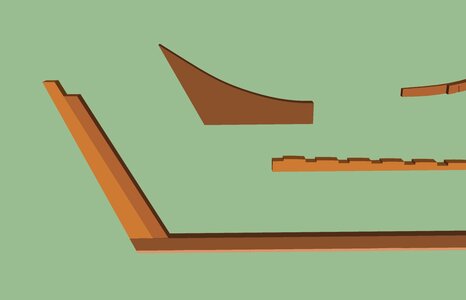

Dimensions of the hull corresponded nearly exactly with a draft of two schooners

constructed in 1815:

Tecumseth and

Newash.

The wreck was specifically identified as H.M. Schooner

Tecumseth, by evidence of the

rig. Three chainplates were recovered, indicating that the mast had three shrouds,

precisely as shown in the drawing. In addition, though the foremast step had

disappeared, bolts remained as testament to its location, which was far forward in the

bow.251 As

Newash had been re-rigged as a brigantine and her foremast moved, the

foremast step would not have been in the same location as that in the draft.

Thus identified, the skeletal vessel was labeled and displayed. Archaeological work and

reconstruction continued at the former naval depot at Penetanguishene, and a museum

called Discovery Harbor (Havre de la Découverte) was established on the grounds. The

museum is home to two replica schooners,

Tecumseth and

Bee, which were

reconstructed on the basis of archaeological and historical evidence and sail the waters

of Penetanguishene Bay and beyond.

Early Publications

A photographer from

Life magazine recorded the salvage in Penetanguishene, and an

article appeared in the publication shortly afterwards. Soon afterwards, experts on Great

Lakes vessels and other relevant topics, including historians C.H.J. Snider, Rowley

Murphy and John R. Stevens, visited the hull, helped identify the wreck and published

scholarly works on the vessel. Snider featured the vessel in his “Schooner Days”

column, published in the

Toronto Evening Telegram.252 Murphy published

“Resurrection at Penetanguishene” in

Inland Seas in 1954. He described the salvage and

illustrated the evidence that allowed the remains to be identified as

Tecumseth. Stevens

prepared “The History of H.M. Armed Schooner

Tecumseth.” In 1961, Stevens’ work

was printed along with Rear Admiral H.F. Pullen’s “The March of the Seamen.”

Together, Stevens’ and Pullen’s work presents a detailed view of the vessels. Pullen

concentrated his historical investigations on a naval uniform button found “between the

planking and the ceiling” of the ship.253 Based on the particular design on the face of

this button, Pullen traced it to the seamen who had traveled overland from New

Brunswick to Kingston in 1814, possibly even Lieutenant Henry Kent himself. Stevens

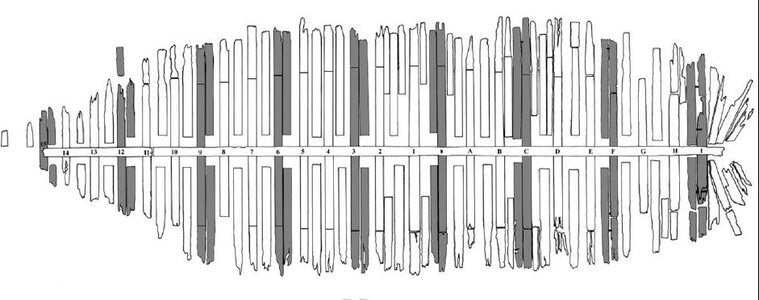

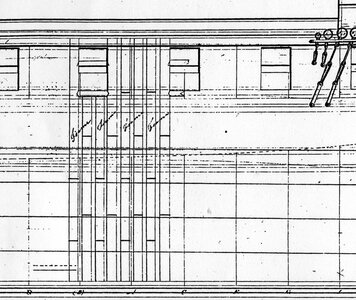

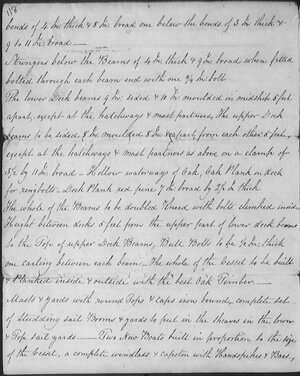

discussed the naval architecture of the schooner in his publication and drafted a number

of views of the hull, including a body plan, midship section, inboard profile, planking

expansion, a redrafting of Moore’s original construction design and a rigging plan.254

1970s Examination and Conservation Efforts

With the hull removed from Penetanguishene harbor, the archaeological remains of

Tecumseth were available for study. The shelter of Discovery Harbour (Havre de la

Découverte) protected the hull from the vandalism that had nearly destroyed

Tigress, but

the remains were still subjected to the elements. In October 1976 Charles Hett, a

conservator, visited the wrecks in Penetanguishene. Hett examined the wooden remains

for signs of deterioration and sent five samples from

Tecumseth’s hull to the Canadian

Conservation Institute for analysis. As one might expect, Hett’s report on the condition

of the hulls was not particularly uplifting.

Both wrecks show the deterioration which is to be expected when wood from

underwater burial is raised and allowed to dry without treatment. The

deterioration is caused by the collapse of weakened cell walls when the water

evaporates, and manifests itself in surface checking, warping, splitting;

dimensional changes which will vary according to the cut of the wood as well as

the type of wood. The damage describe above, and noticeable in varying degrees

in the two shipwrecks can be considered irreversible.

In addition to the damages noted above there is continuing deterioration due

largely to exposure to the elements. Both wrecks appear to be suffering from

extensive deterioration due to micro organisms [sic]. Areas which retain

moisture are most severely affected by this attack, notable the ribs. Considerable

detritus has accumulated in the areas between the ribs and the planking, this

detritus will retain moisture and will provide a continuing source of nutrition for

micro organisms [sic].255

In addition to damage from microorganisms, Hett noticed that mechanical erosion had

occurred while the hull was underwater, leaving the exterior surfaces weakened and the

planking thin.256 The already-fragile hull was subject to additional damage from

environmental effects, and Hett recommended that some type of structure be built over

both hulls, to protect them from further damage.

Hett found traces of preliminary conservation efforts:

Application of a commercial synthetic resin…[has] been made to the

wood and metal parts…This material is visible as a glossy varnish in the

iron, but is not visible on the surface of the wood. It is impossible to see

whether this has achieved any useful purpose, unknown materials should

not be employed for consolidation; in general they cause more problems

than they solve.257

As a result of Hett’s recommendations, both hulls were moved to a permanent display

area on the grounds of the museum. The remains of

Tecumseth, being more substantial

and in better condition than that of

Tigress, are more prominently displayed.

1997 – 1998 Archaeology

Although Jury’s efforts in 1953 have made the remains of H.M. Schooner

Tecumseth

readily accessible for study by nautical archaeologists and the non-diving public alike,

modern archaeological techniques are far superior to those used in the salvage. The hull

certainly suffered tremendously in the dredge’s jaws and evidence of the vessel’s design

and construction was obliterated. As nautical archaeologists can attest, much more

information can be gathered about a shipwreck from studying it in situ, or by careful

excavation and recording, than by simply removing the wreckage off the bottom. The

timbers have also suffered from a minimal amount of preservation treatment and

continual exposure to environmental effects.

While studies undertaken shortly after Jury’s salvage analyzed the remains and

documented the overall history of the vessel,

Tecumseth was not subject to modern

archaeological study. As part of a comprehensive Texas A&M University program to

investigate War of 1812-era shipwrecks in the Great Lakes,

Tecumseth was visited by a

team of student archaeologists, led by graduate student Erich Heinold, over two weeks in

June 1997. The following summer

Newash was surveyed in situ at the bottom of

Penetanguishene harbor. Dimensions were taken of all accessible timbers, using

measuring tapes and goniometers. Significant details of the hulls were drawn, to gain a

better understanding of the precise methods used in constructing the two ships and wreck

plans were made of the existing timbers of both hulls.

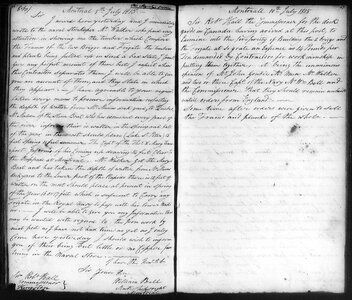

In addition to the archaeological study, Heinold searched for documentary evidence of

the two vessels. Because the ships had served in the Royal Navy, many Admiralty

records survive of their sailing careers and the events of the time; a number are currently

held in the Library and Archives of Canada in Ottawa.

Although Heinold compiled a large amount of archival and field documentation and

made detailed wreck plans (figs. 15 and 16), no final project or publication was

created.

Many of the field notes and copies of Admiralty documents made during the

archaeological investigations are held in the collections of Dr. Kevin Crisman, professor

of Nautical Archaeology at Texas A&M University.

2007 – 2008 Investigations

Because a final publication had yet to be created, additional research was conducted in

preparation for the current project during the summers of 2007 and 2008. The author

made two trips to Penetanguishene, documenting specific details of

Tecumseth each

time. Historical records in the Bayfield Room at the Penetanguishene Public Library

were consulted, and microfilm and transcribed documents at the Library and Archives of

Canada were analyzed for pertinent information.

While preparing this hull and rigging analysis, the author had the opportunity to discuss

matters of history, shipbuilding and seamanship with captains of modern reinterpretations

of contemporary vessels including the U.S. Brig

Niagara and the topsail

schooner

Pride of Baltimore II. Both vessels are reconstructions of War of 1812-era

ships, and the captains contributed insights into potential sailing characteristics of

contemporary sailing vessels.