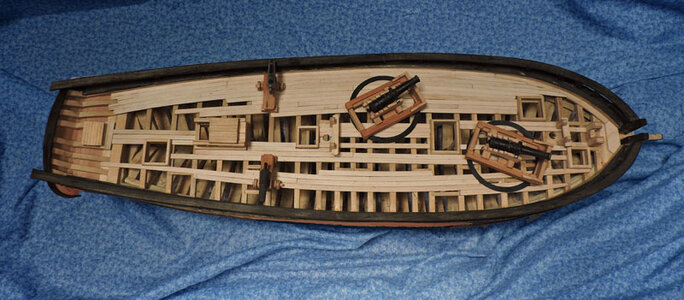

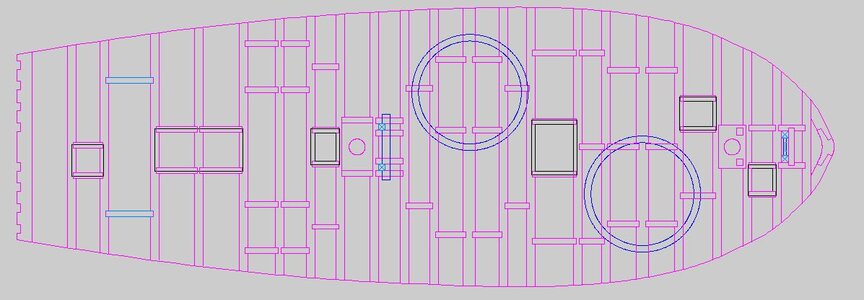

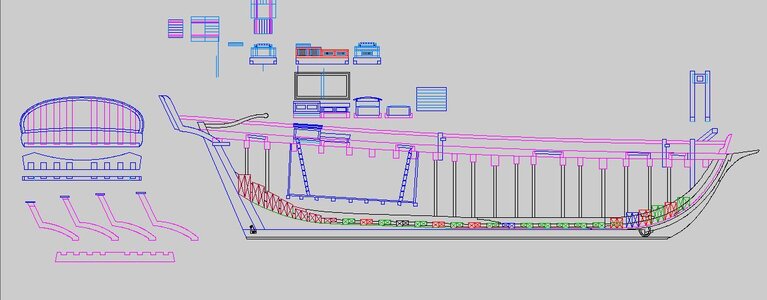

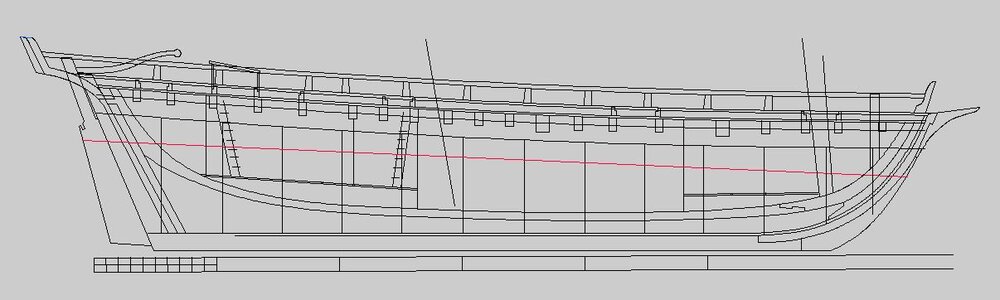

As you can see in post #114 there is nothing on the wreck to assist in the building of the deck but there is the actual deck plan.

So i know what was built but i do not know how it was built. There are questions like where the ends of the deck beams notched into the top of the clamp or notched over the clamp or both? Were deck knees used like lodging, hanging and dagger knees? I know carlings were used because they frame in the fore and aft sides of the hatches. Were ledges used?

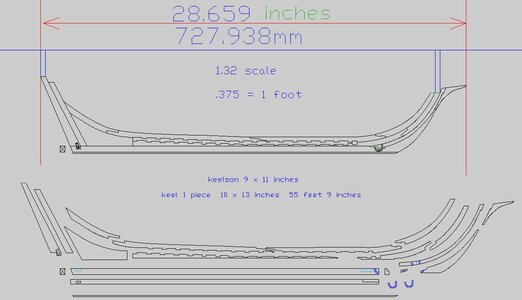

View attachment 255697

What does a model builder do when they run out of information?

here is my approach

Six degrees of separation is the idea that all people on average are six, or fewer, social connections away from each other.

As a result, a chain of " friend of a friend " statements can be made to connect any two people in a maximum of six steps.

It is also known as the six handshakes rule.

how does this apply? well, like any craft or artisan trade there are guilds and unions and schools and apprenticeships programs. What happens is information is taught and passed on within the industry of ship buiding. Ship carpenters and master shipwrights went from yard to yard taking the knowledge with them and spreading it about. The odds are quite hight that the shipwrights who built these ships knew one another and were familiar with the lastest ideas and who was doing what and how.

sit back and take a read about the main shipwrights of the time and place and see if you spot any similarity between them.

while you do the reading i will prep up a 3D model of the deck beams and deck clamp and then get back to the build.

Henry Eckford (1775–1832) was a Scottish-born Shipbuilder, Naval Architect, Industrial Engineer, and entrepreneur who worked for

the United States Navy & the Navy of the Ottoman Empire in the early 19thC. After building a national reputation in the United States

through his Shipbuilding successes during the War of 1812, he became a prominent Business & Political figure in New York City in the 1810s,

1820s, & early 1830s. Eckford was born in Kilwinning, near Irvine, on 12th March 1775, the youngest of 5 sons. As a boy, he probably

trained as a Ship’s Carpenter in the Shipyard at Irvine on the Firth of Clyde. In 1791, at the age of 16, Eckford left Scotland to begin

a 5-year Shipbuilding Apprenticeship with his mother’s brother, the noted Scottish-born Canadian Shipwright John Black, at a Shipyard on

the St Lawrence River in Lower Canada. In 1796, he moved to New York City to work as a journeyman in a Boatyard on the East River.

William Moodie Bell Naval shipwright and farmer.

William Moodie Bell (1777-1837) was the son of John Bell and his wife Ann, née Stenhouse.

He was born on 9 January and baptized on 12 January 1777 in the parish of Aberdour, near

Kirkcaldy in Fifeshire, Scotland. He entered the employ of the Provincial Marine as a naval

shipwright and began his career at Amherstburg, Upper Canada, in June 1799. There he

designed and built vessels for the Great Lakes service. Many of these were lost in 1813 at the

Battle of Lake Erie, after which he was evacuated from Amherstburg, at the time of the retreat

from the Western District, and served thereafter at the Kingston dockyard. The Admiralty's

appointment of Thomas Strickland as Master Builder in Upper Canada displaced Bell from

that position, but in 1814 he was appointed as Strickland's assistant. Upon Strickland's death

in 1815, Bell became Acting Master Builder in Upper Canada until the end of 1816, when the

establishment at Kingston was reduced and Bell returned to Scotland.

Having succeeded in obtaining a government pension, Bell returned to Canada, where he

seems to have considered going into partnership with his brother John Bell (1779-1841) and

a French Canadian shipbuilder, François Romain, at Quebec, before settling down as a farmer

at Little River, Lower Canada.

MUNN, ALEXANDER, shipbuilder and shipowner; born 26 Sept. 1766 in Irvine, Scotland, son of John Munn, shipbuilder, and Catherine Edward;

m. 6 Dec. 1797 Agnes Galloway at Quebec, Lower Canada, and they had 11 children, of whom six died in infancy; d. there 19 May 1812.

Alexander Munn is a shadowy figure. Since his personal and business records have apparently not survived, the only direct evidence

about him consists of disparate references found in routinely generated sources such as notarial records, newspaper notices, and ship

and church registers. Difficult to work, these sources do not yield a rounded portrait. But the broad picture that emerges clearly indicates

he was a leading Quebec shipbuilder in the beginning stages of that highly productive sector of the city’s economy. It is Munn’s entrepreneurial function that provides the focus in the following sketch.

Munn undoubtedly learned the “mysteries” of shipbuilding from his father before immigrating to Quebec in or before May 1793. In the 1790s

the establishment of big-ship construction in the city implied a transfer of skills and capital in person from Britain. Certainly the cumulative evidence about British American shipbuilding in general shows a heavy reliance on Britain for technology (in the wide sense of the term), capital, and markets; the emergence of a native-born shipbuilder before about 1830 is rare.

Munn first appears in Quebec records in February 1794 when he described himself as a “ship carpenter” in a notarial act; by 1803, however,

he was calling himself a “shipbuilder.” These descriptions superficially suggest that he rose from journeyman to master craftsman within

the craft hierarchy, but in shipbuilding at Quebec at the turn of the 19th century the craft system seems to have been a vestigial formality

which bore little weight in the actual economy of shipyards. Apprenticeships, which were common, were clearly used by employing shipbuilders

primarily as a legal device to circumvent labour shortages, and the status of master shipbuilder did not entail any special political

privilege as it did at Saint John, N.B., where it carried with it admission to the freedom of the city.

The change in Munn’s title is more likely explained by what appears to have been a well-observed unwritten rule reserving the use of

the appellation of shipbuilder to those who operated substantial yards, as Munn did by the later date.

Beginning in the mid 1790s, at premises leased from the firm of Johnston and Purss [see James Johnston*] on the King’s Wharf in Lower Town,

and after 1806 as proprietor of an extensive shipyard at Anse des Mères, Munn frequently launched two large vessels a year, one in the

spring and the other in the fall. In addition, a certain amount of repair work seems to have been turned out from his yards. A conservative

estimate of his new production, based mainly on the certificates of ship registry, would be 17 vessels having an aggregate of 4,470 tons,

built between 1798 and 1812 inclusive. The actual launchings may have exceeded these figures considerably since certificates do not always

fully identify builders and no other satisfactory source exists. As with the bulk of the tonnage built in British America in the century

after the American revolution, Munn’s ships and brigs were constructed for the British market. His known production indicates that he built

primarily on his own account, or under contract with a British agent, an example of the latter arrangement being an 1807 agreement with

ohn Drysdale for construction of a 435-ton ship. Since contract building appears to have involved a flow of capital from the future owner

to the builder at specified periods during construction, Munn’s registration of ten vessels in his own name testifies to his strong financial

position; he possessed, or had access to, sufficient capital to avoid the dependence usually imposed by contract construction. The source of the capital with which he established operations is unknown; presumably he drew from his family network, but it seems a safe assumption that much of the subsequent finance was generated from sales.

Alexander was one of at least five contemporary shipbuilding Munns, four of whom established themselves in Lower Canada and were probably

of the same family. The fifth, Alexander’s brother, James, was a shipbuilder at Troon, Scotland, in 1800 when, following the death of their

father, Alexander gave him power of attorney to look after his shipping interests in Scotland. He may have been the same James Munn,

shipbuilder, located at Irvine in 1803 and mentioned in the correspondence of John Scott and Sons, a shipbuilding firm of Greenock, Scotland,

and Saint John, N.B.; he was one of the first steamship builders on the Clyde. A John Munn, who may have been Alexander’s brother, began building at Quebec as early as the fall of 1797, and within a few years he had brought his young son John* into partnership to run a shipyard in the faubourg Saint-Roch, the area of the port, bordering the Rivière Saint-Charles, which later in the century was to have the largest concentration of shipbuilding in British America. David Munn, who may also have been Alexander’s brother, operated a shipyard next to Molson’s Brewery in the Montreal suburb of Sainte-Marie from 1805 to about 1820, and much of his construction may have been financed by the Greenock merchant Robert Hunter, with whom he registered 14 of 17 vessels, totalling 4,916 tons. David also had business interests at Quebec; in 1812 he guaranteed the performance of John Munn and Son in a contract to build a ship for a London merchant. The same year he was one of two shipbuilders who valued the vessels in Alexander’s estate, and two years later he rented Alexander’s shipyard from the latter’s widow.

Given the paucity of evidence, it is difficult to trace in detail the operations of the early colonial shipyards and the social formations which developed from them, not least in the instance of Alexander Munn. Nevertheless, the general outline is sufficiently clear to allow assertion that the shipyard represented a vanguard stage in colonial productive enterprise in terms of unit size, division of labour, rhythm of employment, control of materials, labour discipline, and capital requirements. Similarly, shipbuilders may be seen as a new class of entrepreneurs in the colonial setting, a variety of manufacturer as different from the contemporary master artisan as from the industrial capitalist who followed him. If only broad generalizations can be made about the work and financial structures of Munn’s shipyard operation – principally from the size of vessels constructed (of those registered, between 119 arid 469 tons) – there are a few precise indications of his own economic and social status. The rents for his shipyard site at the King’s Wharf amounted to nearly £400 annually by about 1800, and in 1806 he paid the bankrupt estate of the London

shipbuilders William and John Beatson £3,050 for the shipyard at Anse des Mères. In 1812 an inventory of his movable property

(but not of the land, buildings, or cash) indicated that effects in his “Yard & Stores” were worth £1,055; as well, a sloop afloat was valued

at £300, a new brig, the James, at £2,700, and a new ship on the blocks, the Diana, at £4,000. In his marriage agreement in 1797

Alexander promised Agnes £300 on his death. His estate, for which she was administratrix, did indeed leave her well established.

She lived on in a newly built, substantial stone house, employing a manservant for at least one year at a salary of £20. The shipyard was

subsequently leased on an annual basis to various individuals, including David and John Munn, and finally sold in 1839 to James Bell Forsyth*

for £6,250.

Munn’s only evident sally into a public position took place around 1807 when he became acting surveying officer of the port. Certainly he was

a privileged member of Quebec society, enjoying advantages that clearly stemmed from being a shipbuilder. In addition to trips to Britain,

there are signs of gracious living in the inventory of his estate: two calèches and three carrioles; a lady’s side-saddle; and a piano. Also,

for the education of the children, Munn had employed a tutor who lived in. These luxuries were beyond the reach of his employees;

one of his apprentices, for example, was engaged in 1807 for but £8 per year plus meat, drink, and lodging. There can be little doubt that

they were also beyond the resources of master craftsmen, then the typical entrepreneurs of production outside shipbuilding in the

pre-industrial economy of British America.

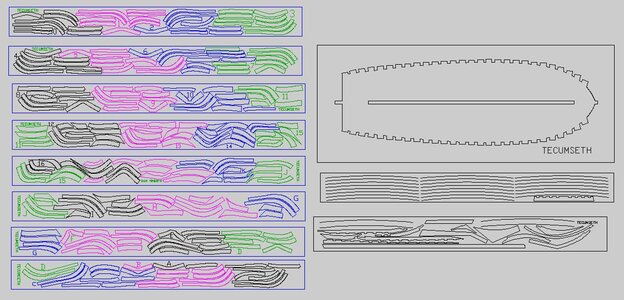

Stole this idea Dave and it's working brilliantly so far. Definitely a good bang for your buck, I did all these planks and haven't even pulled off the first layer. BTW is a China Marker made in the USA the same thing as an American Flag made in China?

Stole this idea Dave and it's working brilliantly so far. Definitely a good bang for your buck, I did all these planks and haven't even pulled off the first layer. BTW is a China Marker made in the USA the same thing as an American Flag made in China?