.

@fred.hocker

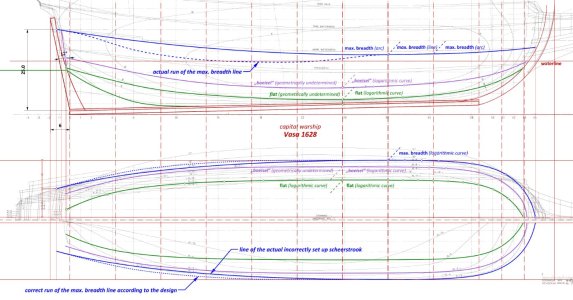

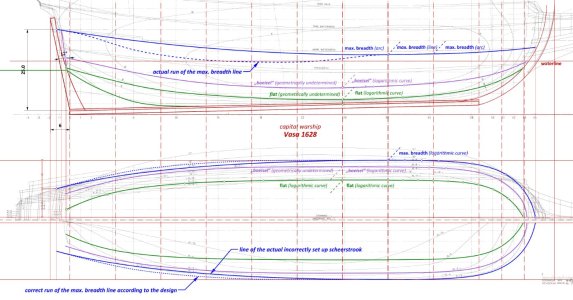

Fred, I think I have finally found the right solution for this aberrant shape in the aft section of the

Vasa's hull. In short: it is not the bottom of the hull at the aft part of the ship that has been widened, but rather the opposite, yet with a similar effect — the line of greatest breadth (physically materialised by the

scheerstrook/master ribband) is too narrow (flat) for this area. This is most likely the result of careless workmanship in the style of,

nomen omen, intuitive shipbuilding ‘by eye’ instead of strictly following the ship's design. But first things first.

The 3-foot trim on the museum plans seems to be too large, and only after reducing it to 2 feet can the longitudinal design lines be consistently defined as regular geometric curves that also match the shapes of the ship as rendered in the museum plans from 1970/80.

Nevertheless, the original ship design by Hybertsson or Jacobsson must have been for horizontal keel orientation, so working with a longitudinally inclined hull, and at an inappropriate angle, was a particularly troublesome, complicated task. This is more of a piece of information for other potential researchers of the ship based on these plans than a complaint.

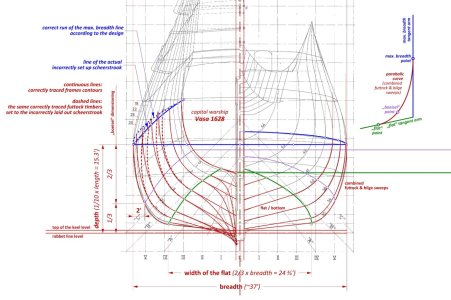

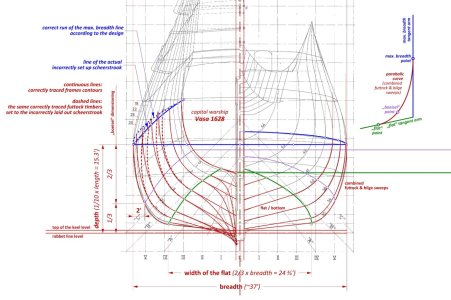

I have adopted or determined the following dimensions:

Original dimensions (length/breadth/depth): 153 / 34 / 15.3 (length/breadth ratio = 4.5 : 1, length/depth ratio = „classical” 10 : 1, but for depth measured from the rabbet line, not from the keelson, up to the maximum breadth line, which in turn coincides with the deck line).

Dimensions as modified by Jacobsson (length/breadth/depth): 153 / ~37 (= 34 + 1.5 + 1.5) / 15.3

These latter dimensions match the museum plan particularly well.

Deadrise at the master frame: 1.5 (measured from the rabbet line) or 1 (measured from the upper edge of the keel)

Width of the flat: 24 2/3 (= 2/3 of the breadth)

‘Boeisel’ line at the master frame: as in the diagram (reconstructed according to the specifications of

Prins Willem of 1630, i.e. a ship with very similar dimensions).

In the case of the Vasa, I decided to abandon elliptical curves for defining the contours of the frames (as shown before) in favour of parabolic curves, because I realised that the so-called ‘boeisel’ line, which is actually ‘mandatory’ in Dutch designs for large ships, is nothing more than a necessary element for generating parabolic curves that define the contours of the frames. Consequently, I also reconstructed the ‘boeisel’ line for the

Vasa 1628.

In practice, parabolic curves can be very well approximated by a simple strip. To verify this, I even conducted a test in the spirit of so-called experimental archaeology, using a wooden strip fixed in a vice. All one have to do is pull the strip vertically (i.e. according to the orientation of the hull) until its curvature coincides with the point determined by the coordinates taken from the ‘boeisel’ line, and

voilà, the frame contour is ready (more precisely: the contour of the combination of bilge and futtock sweeps). A fairly effective, quick method with sufficient repeatability, to use an engineering term.

Getting to the heart of the matter, it turns out that in the top view, the maximum breadth line and the ‘boeisel’ line unnaturally converge at the aft section of the ship, which is more likely an assembly failure than a design flaw. In fact, it appears that the contours of the futtock timbers were correctly traced, that is according to the correctly defined maximum breadth line. However, the physically installed

scheerstrook during the actual assembly of the hull did not comply with the design in that it turned out to be too flat laterally, which in turn resulted in the incorrect orientation of the installed futtock timbers. I have shown this phenomenon in the attached diagram, where it can be concluded that the curvature of the correctly traced frames corresponds very well with their corresponding contours on the museum plan.

In summary, if the above solution is right, then the

Vasa's disaster in 1628 can be attributed most likely to sloppy workmanship, albeit exceptional in this particular case, or, if one prefers, to the intuitive assembly of the

scheerstrook ‘by eye’ instead of in accordance with the previously made design of the ship. If the run of the

scheerstrook in the aft section had the correct shape, i.e. more convex, in accordance with the design, the ship would have gained (or rather not lost) twice: the actual line of maximum breadth would be in its correct place, i.e. at the appropriate height, benefiting the so-called shape stability, and the volume of the submerged part of the hull would be greater, also benefiting so-called ballast stability (in particular, allowing for an increase in ballast without bringing the gun ports too close to the water).

Would more careful assembly in this respect have prevented the disaster? Appropriate calculations would have to be made, but that is perhaps a task for someone else...

.