- Joined

- Dec 1, 2016

- Messages

- 6,379

- Points

- 728

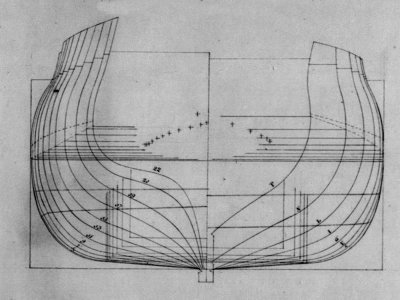

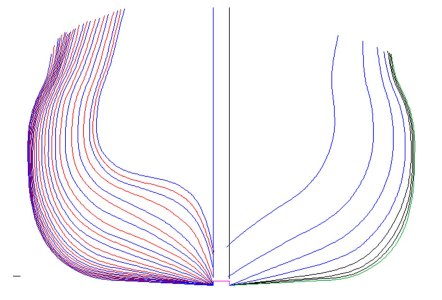

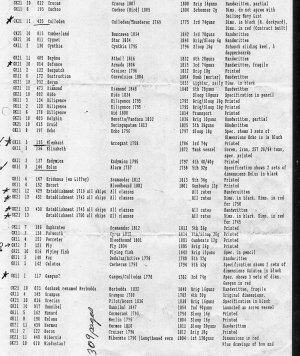

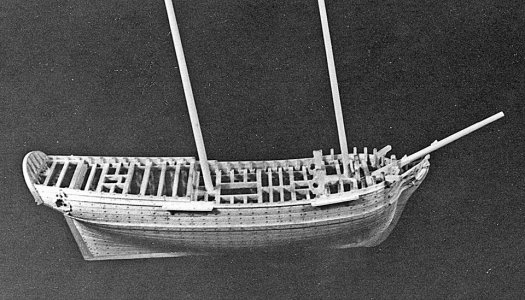

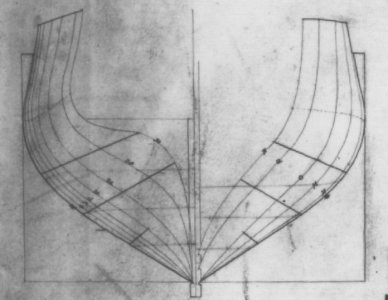

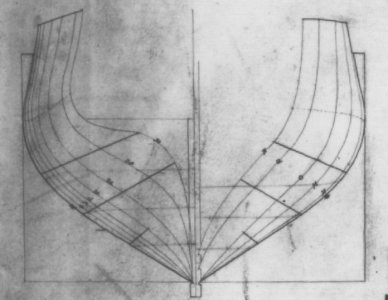

about bodyplans here i am using the bodyplan of the a heavy armed frigate Princess Charlotte built on Lake Ontario in 1812. What makes this unique is the extreme V shape of the hull. War ship on the oceans needed to carry supplies because they were out to sea for months on end. On the lakes they sailed for a short time so there was no need to carry supplies. The sharper the hull the faster it could move. This ship was built for speed.

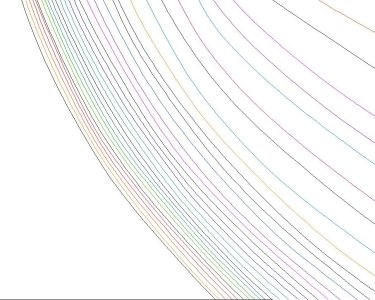

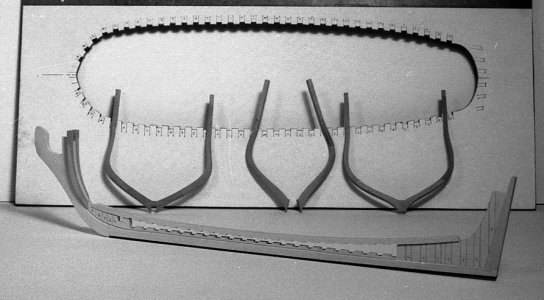

first image is the original bodyplan which has only the station lines

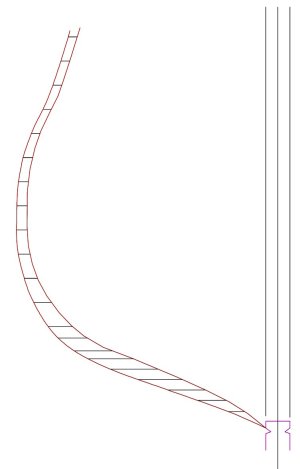

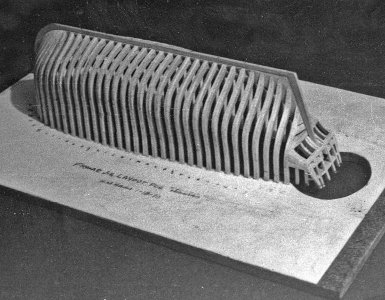

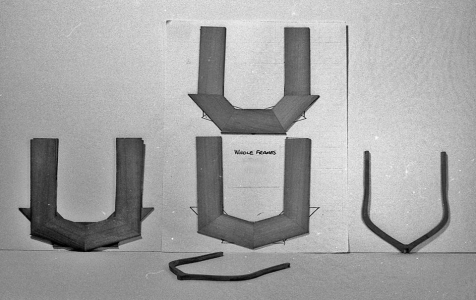

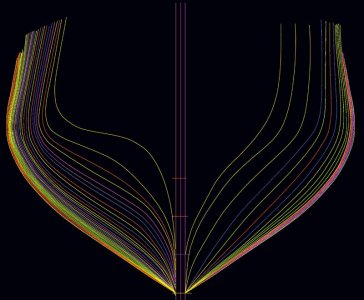

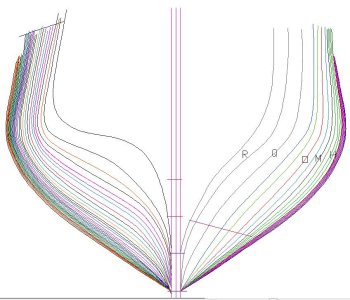

building a framed hull you need all the frame shapes like in this bodyplan

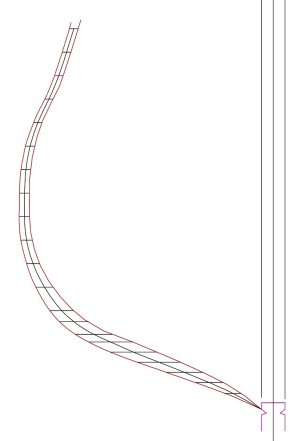

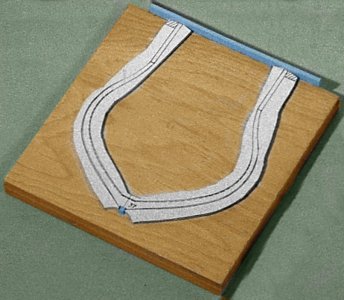

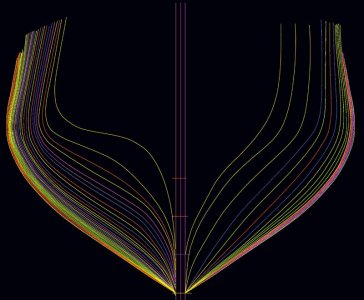

when you draw in all the frame shapes the lines run together

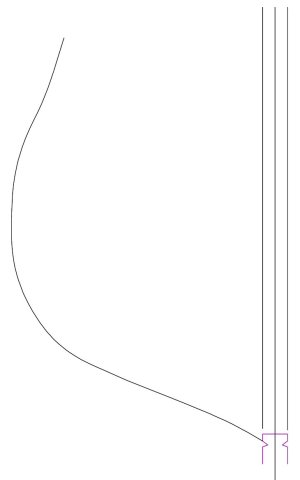

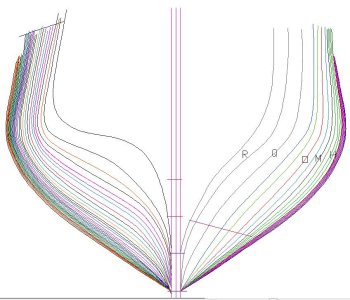

drawing with CAD you can zoom way in and draw all your lines. but if you doing this with a pen on paper the lines will all run together. The trick in drawing a bodyplan by hand is to take the original print it out and take it to an office supply place that makes copies. Have the blow the bodyplan way up in size. I am saying BIG like 20 x 24 inch. Then when you finished you reduce the drawing.

first image is the original bodyplan which has only the station lines

building a framed hull you need all the frame shapes like in this bodyplan

when you draw in all the frame shapes the lines run together

drawing with CAD you can zoom way in and draw all your lines. but if you doing this with a pen on paper the lines will all run together. The trick in drawing a bodyplan by hand is to take the original print it out and take it to an office supply place that makes copies. Have the blow the bodyplan way up in size. I am saying BIG like 20 x 24 inch. Then when you finished you reduce the drawing.