- Joined

- Jul 17, 2024

- Messages

- 75

- Points

- 113

15 Coppering part 1

Before we left for England on 6 June 2023 to visit the Victory, I had deployed a test for ageing the copper plates, called patination. You can do this with a mixture of ammonia, vinegar and salt. Initially, the process was slow and the result was very different on the various plates. Then I had abandoned the trial a bit and let time do its work. Well aged they were, even so much so that some of the platelets dissolved.

I imagine there will be modellers among us who will get a kick out of this, but not me particularly. Regardless of how this will work in practice with so many plates, I didn't like it at all, this look.

Results below. Everyone can think what they like about it.

After returning from England, I decided to take the gamble after the patination trial and age the entire quantity of copper plates for one side. Since I didn't have ammonia in the house, they first spent a few days in a mixture of vinegar and table salt. Very slowly, after about four days, I started to see some changes to the plates, but it was slow going. A few days later the ammonia was in the house and I did a dash of it. A day later, to my surprise, I saw that the process had accelerated. The entire liquid had turned bright blue and the plates started to clump together. Quickly took everything out and rinsed/washed well with clean water. And aged they were. At the moment, they are drying. See the results below.

As time passed, however, the look of the patination process became more unsettled than I had hoped. When I took the previous photos of the patination process, the plates were probably not completely dry yet. By now they are, and I feel that the process of ageing is still continuing at this point.

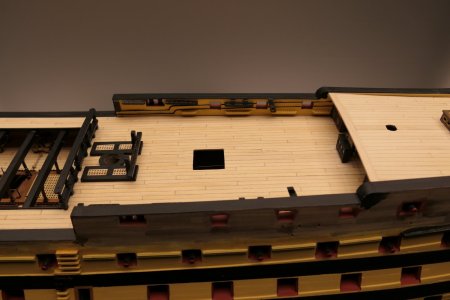

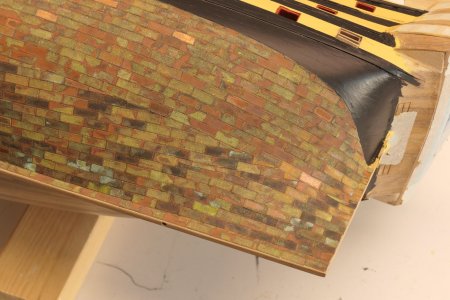

After a while, the time had come, the coppering could begin.

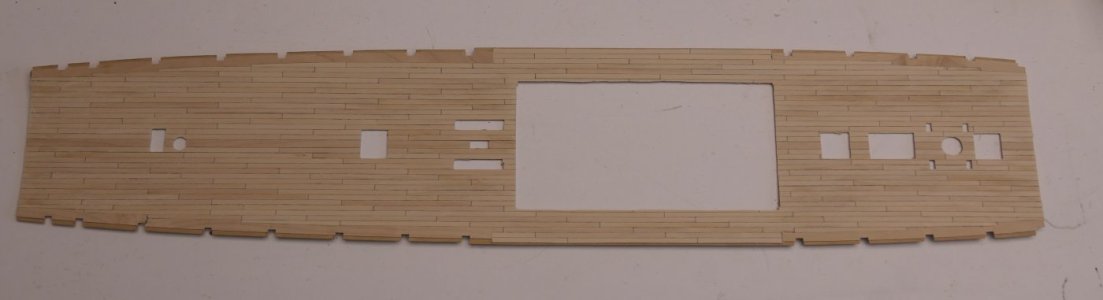

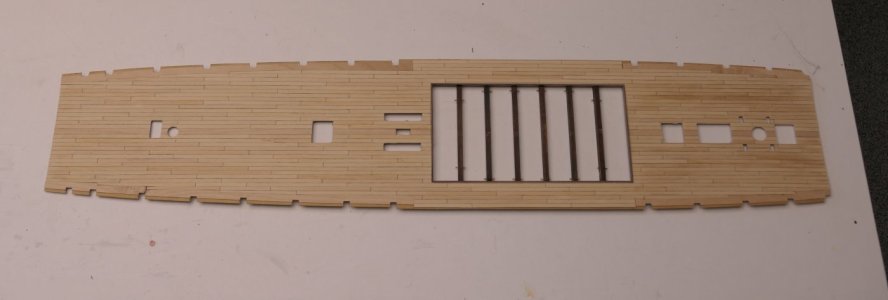

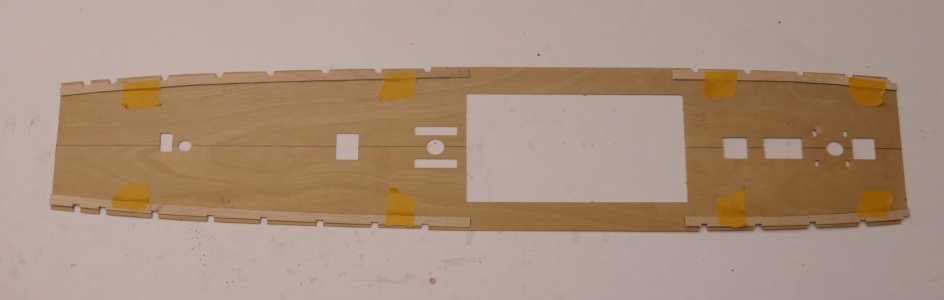

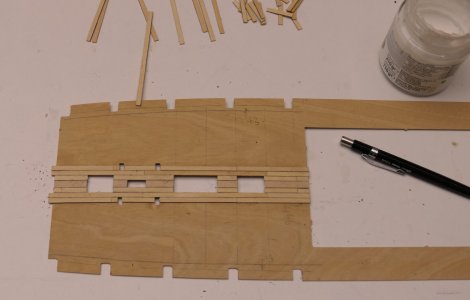

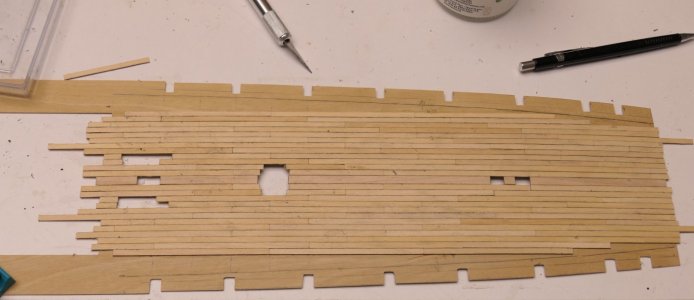

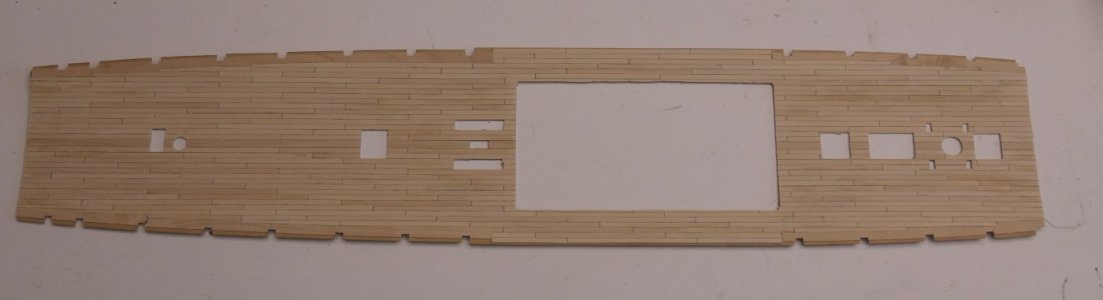

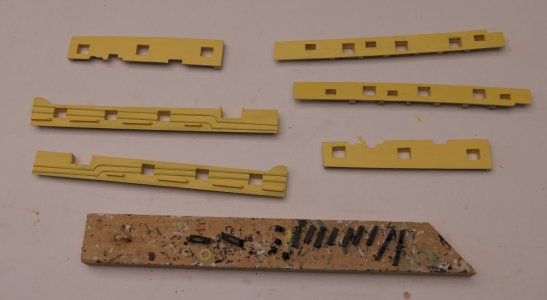

In short: I started with a slat under the top row of plates.

Then a strip of double-sided adhesive tape on it, 6mm wide, roughly up to the 4e gun port from fore and aft, from the centre 11 plates to the left and 11 to the right. When there are 7 rows on it in half-brick a batten below that deflects to the intersection of the waterline with the bow and stern. Then lay the 7e row to these intersection points and seal the sections above with plates. When these two points are completely closed, continue along the 7e row with the 8e to the 12e row. The lower section starts against the keel and is only cut against the first section.

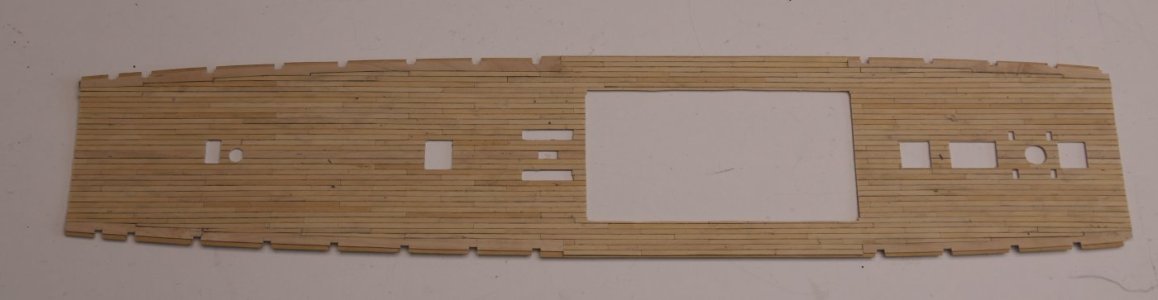

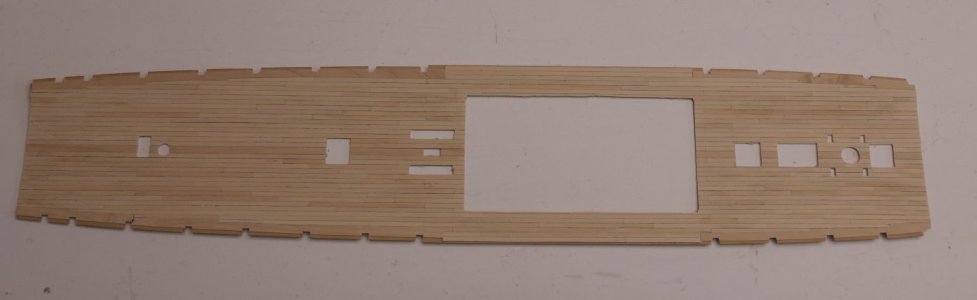

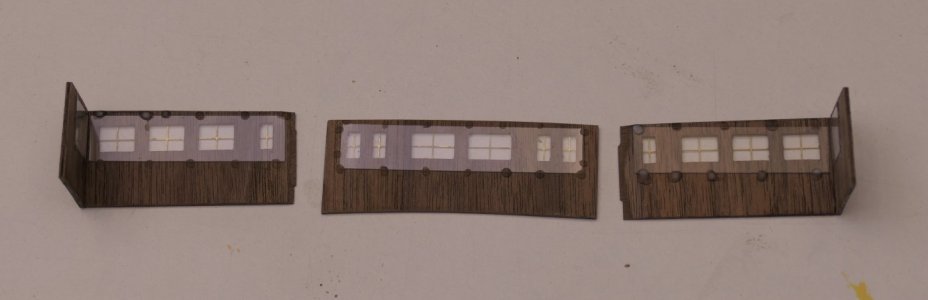

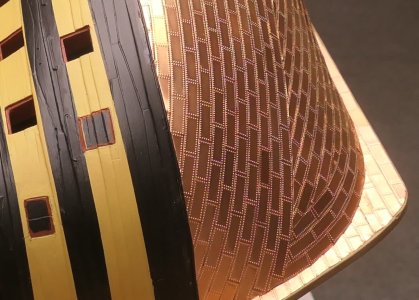

The pictures below speak for themselves, I think.

I admit, it takes some getting used to. The pictures were taken from above with the boat on its side. I am curious to know what you guys think. At least I was satisfied at that point.

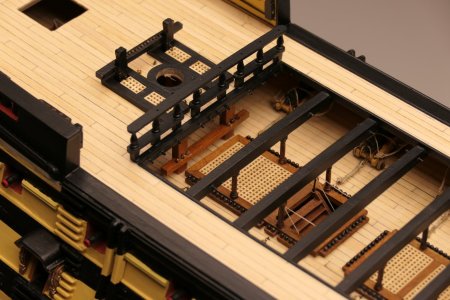

After completing the first 12 rows from the waterline, I started against the keel. First I covered the keel, so that the plates on the hull fall over this and you don't see a seam. I kept the plates on the keel a mm back along the edges, so the plates won't get caught everywhere later. This edge and the ends of the keel were later treated with clear varnish.

At the rear, I still had to use a stealer to get the plates on the fuselage somewhat in smooth lines.

The last rows of plating all zero off against the 12e row from the top. In the middle section, the plating is closed over about half a length with half-width plates.

Resuming:

As I mentioned earlier, I was actually caught off guard by an acceleration in the chemical reaction with the first batch of plates (1 full bag of the 2 provided). This created the variegated colour palette. When I had the first 12 rows on, I began to have some doubts about whether 1 bag would be enough for one side. So no, or maybe if you have no waste at all.

So then started the patination process with a second batch. This went slowly and when I saw that the plates had all turned dark brown, I quickly removed them from the chemical bath and rinsed them off. The result was beautiful, but the plates were still wet.

At that point, I seriously considered removing the already applied plates and starting over. But when the plates were dry, the result turned out to be disappointing anyway, they had become even more furry.

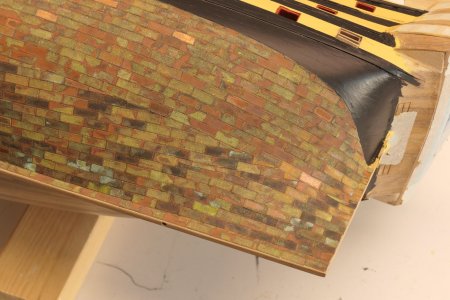

In the end, I mixed both sides. You can see the result in the picture below. Despite this setback, I am still satisfied with the final result.

Patination kept me pretty busy over the following weeks. As it turned out, it was still a living process. I will use some photos to show you what happened.

The last photo was the situation immediately after the coping was completed, on 18 July.

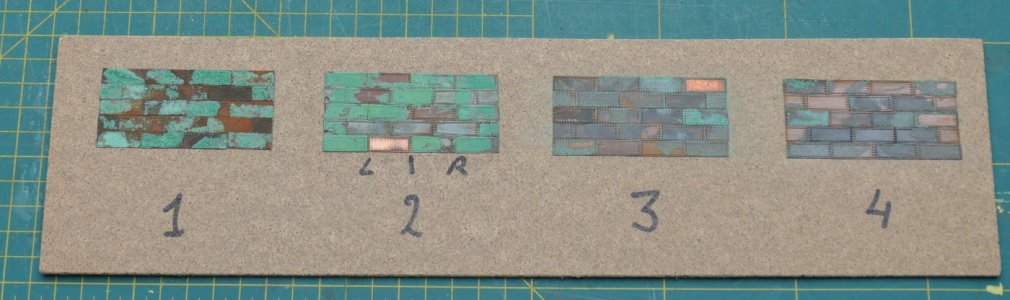

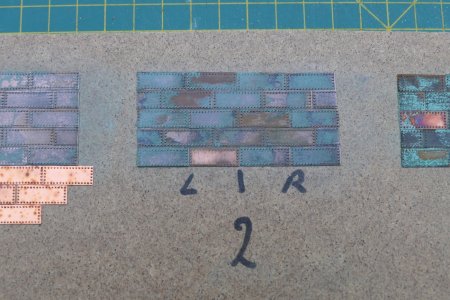

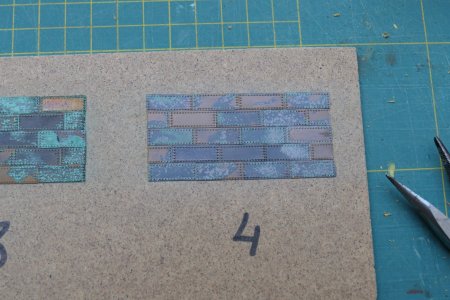

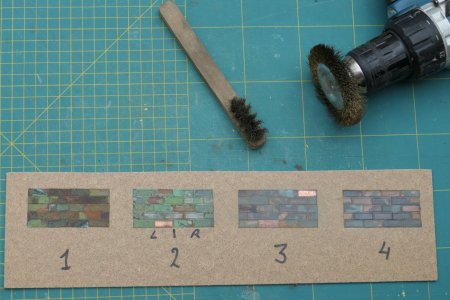

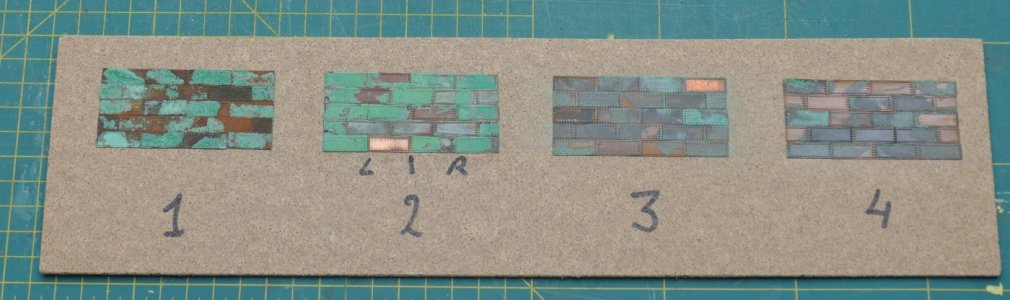

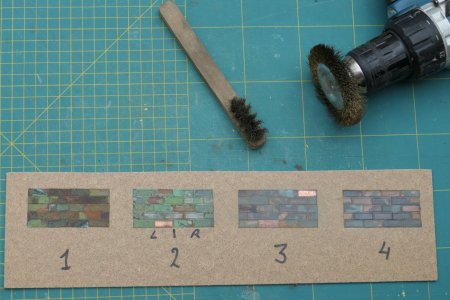

Since the variegated result still kept me busy, I made a small test piece on 27 July, to which I applied a number of edits. See photo below.

In detail 1, the plates are untreated, so as they are on the ship.

For detail 2, I applied a layer of varnish to insulate the panels and fix the seams somewhat.

Detail 3 shows an edit of a light treatment with a small brass brush

Detail 4 is the result after I used the round brass toll to brush the plates very lightly and briefly.

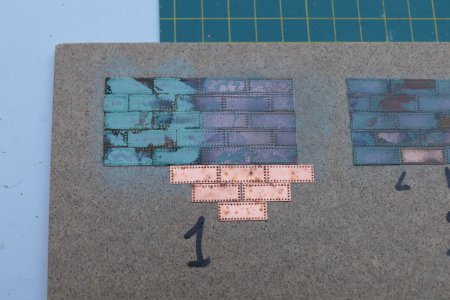

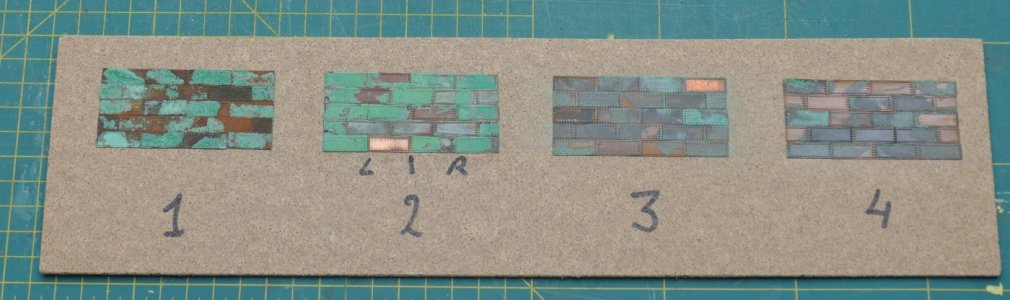

On 6 August, the trial plate result was as shown in the photos below. The plates on the hull are also clearly changing.

My preliminary conclusion at the time was as follows:

Test piece 1: where there was some kind of tarnish on the plates, it changes to a green layer of copper oxide. This process seems to continue.

Test piece 2: varnishing has an adverse effect on the appearance. A milky-white-like layer remains on some plates, which is not nice.

Test piece 3: here were initially scratches, which are clearly fading in a later phase.

Sample 4: This treatment gives a much calmer look and is the least subject to change. At the moment, hardly any difference is noticeable. The shiny does come off a little.

During the patination process, a kind of deposit apparently formed on the plates, accelerating the ageing process. If you remove this deposit by brushing, you slow down this process again. At the moment, I was tempted to brush the copper plates with the spinning top, as in test piece 4, but that can always be done.

The expectation was that discolouration in practice would bring about a more even image.

If this were to continue with me, the plates might soon turn completely green. Then I will get close.

Problem then became, "How do I get this process stopped, otherwise all the plates will soon perish?"

The varnish layer is of water-based varnish. Beneath the varnish layer, the process also continues and the pictures turn greener and greener.

For now, just wait and see what happens next.

Before we left for England on 6 June 2023 to visit the Victory, I had deployed a test for ageing the copper plates, called patination. You can do this with a mixture of ammonia, vinegar and salt. Initially, the process was slow and the result was very different on the various plates. Then I had abandoned the trial a bit and let time do its work. Well aged they were, even so much so that some of the platelets dissolved.

I imagine there will be modellers among us who will get a kick out of this, but not me particularly. Regardless of how this will work in practice with so many plates, I didn't like it at all, this look.

Results below. Everyone can think what they like about it.

After returning from England, I decided to take the gamble after the patination trial and age the entire quantity of copper plates for one side. Since I didn't have ammonia in the house, they first spent a few days in a mixture of vinegar and table salt. Very slowly, after about four days, I started to see some changes to the plates, but it was slow going. A few days later the ammonia was in the house and I did a dash of it. A day later, to my surprise, I saw that the process had accelerated. The entire liquid had turned bright blue and the plates started to clump together. Quickly took everything out and rinsed/washed well with clean water. And aged they were. At the moment, they are drying. See the results below.

As time passed, however, the look of the patination process became more unsettled than I had hoped. When I took the previous photos of the patination process, the plates were probably not completely dry yet. By now they are, and I feel that the process of ageing is still continuing at this point.

After a while, the time had come, the coppering could begin.

In short: I started with a slat under the top row of plates.

Then a strip of double-sided adhesive tape on it, 6mm wide, roughly up to the 4e gun port from fore and aft, from the centre 11 plates to the left and 11 to the right. When there are 7 rows on it in half-brick a batten below that deflects to the intersection of the waterline with the bow and stern. Then lay the 7e row to these intersection points and seal the sections above with plates. When these two points are completely closed, continue along the 7e row with the 8e to the 12e row. The lower section starts against the keel and is only cut against the first section.

The pictures below speak for themselves, I think.

I admit, it takes some getting used to. The pictures were taken from above with the boat on its side. I am curious to know what you guys think. At least I was satisfied at that point.

After completing the first 12 rows from the waterline, I started against the keel. First I covered the keel, so that the plates on the hull fall over this and you don't see a seam. I kept the plates on the keel a mm back along the edges, so the plates won't get caught everywhere later. This edge and the ends of the keel were later treated with clear varnish.

At the rear, I still had to use a stealer to get the plates on the fuselage somewhat in smooth lines.

The last rows of plating all zero off against the 12e row from the top. In the middle section, the plating is closed over about half a length with half-width plates.

Resuming:

- Applying the plates did not disappoint me at all. Actually done in no time at all.

- I marked the plates with a scriber, after which they could be cut neatly straight with the self-made "guillotine". Cutting with an old pair of kitchen scissors also works well, but then the plates quickly warp.

- Gluing with the double-sided tape is a godsend. I didn't have the impression that the patination was bad for the adhesion to the tape. The stuff sticks just fine, but the biggest advantage is that the glue joint remains flexible so that something can always be corrected. This is in contrast to superglue. The plates stay nice and clean. No glue remains. And the plates stick over the entire surface.

As I mentioned earlier, I was actually caught off guard by an acceleration in the chemical reaction with the first batch of plates (1 full bag of the 2 provided). This created the variegated colour palette. When I had the first 12 rows on, I began to have some doubts about whether 1 bag would be enough for one side. So no, or maybe if you have no waste at all.

So then started the patination process with a second batch. This went slowly and when I saw that the plates had all turned dark brown, I quickly removed them from the chemical bath and rinsed them off. The result was beautiful, but the plates were still wet.

At that point, I seriously considered removing the already applied plates and starting over. But when the plates were dry, the result turned out to be disappointing anyway, they had become even more furry.

In the end, I mixed both sides. You can see the result in the picture below. Despite this setback, I am still satisfied with the final result.

Patination kept me pretty busy over the following weeks. As it turned out, it was still a living process. I will use some photos to show you what happened.

The last photo was the situation immediately after the coping was completed, on 18 July.

Since the variegated result still kept me busy, I made a small test piece on 27 July, to which I applied a number of edits. See photo below.

In detail 1, the plates are untreated, so as they are on the ship.

For detail 2, I applied a layer of varnish to insulate the panels and fix the seams somewhat.

Detail 3 shows an edit of a light treatment with a small brass brush

Detail 4 is the result after I used the round brass toll to brush the plates very lightly and briefly.

On 6 August, the trial plate result was as shown in the photos below. The plates on the hull are also clearly changing.

My preliminary conclusion at the time was as follows:

Test piece 1: where there was some kind of tarnish on the plates, it changes to a green layer of copper oxide. This process seems to continue.

Test piece 2: varnishing has an adverse effect on the appearance. A milky-white-like layer remains on some plates, which is not nice.

Test piece 3: here were initially scratches, which are clearly fading in a later phase.

Sample 4: This treatment gives a much calmer look and is the least subject to change. At the moment, hardly any difference is noticeable. The shiny does come off a little.

During the patination process, a kind of deposit apparently formed on the plates, accelerating the ageing process. If you remove this deposit by brushing, you slow down this process again. At the moment, I was tempted to brush the copper plates with the spinning top, as in test piece 4, but that can always be done.

The expectation was that discolouration in practice would bring about a more even image.

If this were to continue with me, the plates might soon turn completely green. Then I will get close.

Problem then became, "How do I get this process stopped, otherwise all the plates will soon perish?"

The varnish layer is of water-based varnish. Beneath the varnish layer, the process also continues and the pictures turn greener and greener.

For now, just wait and see what happens next.