- Joined

- Jun 29, 2024

- Messages

- 1,556

- Points

- 438

Charlie, A comment relative to your question but I’ll leave exactly modeling techniques to others.

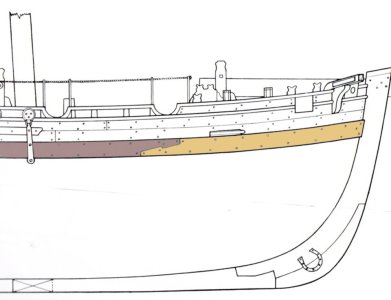

The great weakness of wooden ships was their longitudinal strength. In the days before modern waterproof adhesives ships were a collection of pegged together wooden parts each one trying to move vs its neighbors as the vessel flexed in a seaway. As these ships aged the sliding of individual hull planks relative to each other squeezed out the caulking. Old ships often required continuous pumping to stay afloat.

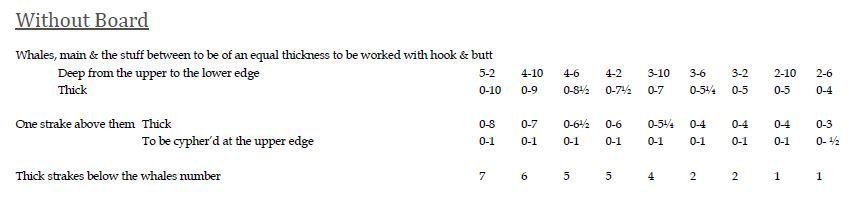

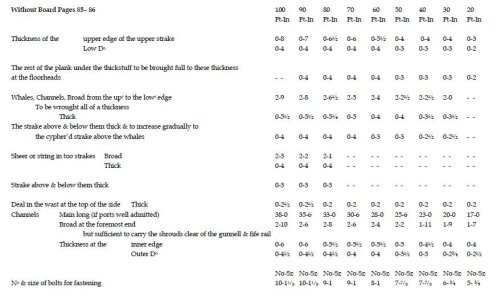

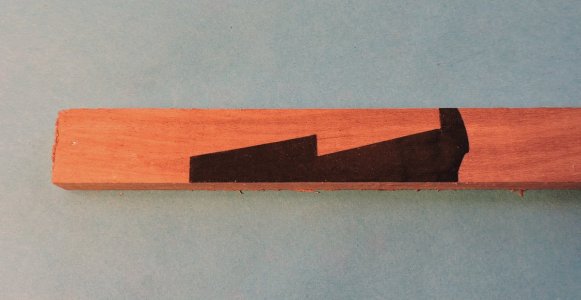

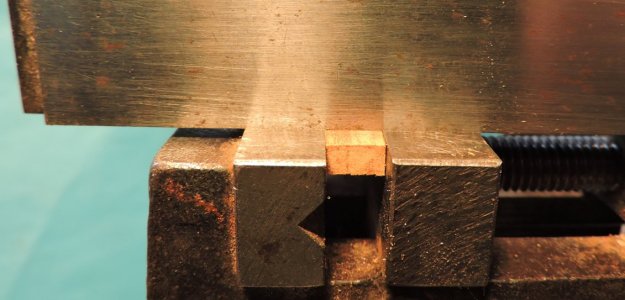

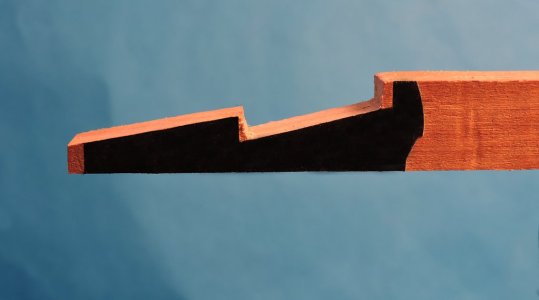

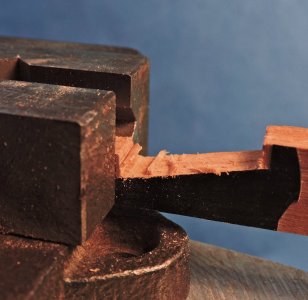

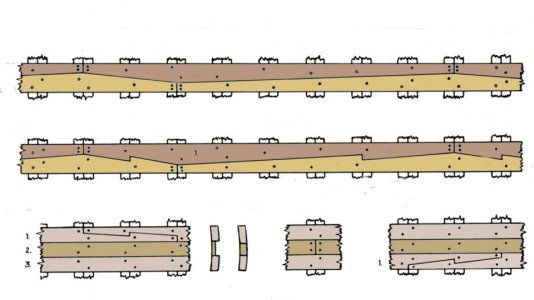

The heavy Wales, were, therefore, principal longitudinal strength members and special scarphs were often used to lock them together to resist longitudinal bending loads. There were Stock scarphs, Hook and Butt, and probably more. All of these require precision woodworking to model properly. I know nothing about your model and t what degree of historical accuracy you wish to achieve. If your model is “representative” it’s ok to skip this detail. If you’re trying to replicate exact shipbuilding technology, you should research this.

Stock scarphs, Hook and Butt, and probably more. All of these require precision woodworking to model properly. I know nothing about your model and t what degree of historical accuracy you wish to achieve. If your model is “representative” it’s ok to skip this detail. If you’re trying to replicate exact shipbuilding technology, you should research this.

Roger

The great weakness of wooden ships was their longitudinal strength. In the days before modern waterproof adhesives ships were a collection of pegged together wooden parts each one trying to move vs its neighbors as the vessel flexed in a seaway. As these ships aged the sliding of individual hull planks relative to each other squeezed out the caulking. Old ships often required continuous pumping to stay afloat.

The heavy Wales, were, therefore, principal longitudinal strength members and special scarphs were often used to lock them together to resist longitudinal bending loads. There were

Stock scarphs, Hook and Butt, and probably more. All of these require precision woodworking to model properly. I know nothing about your model and t what degree of historical accuracy you wish to achieve. If your model is “representative” it’s ok to skip this detail. If you’re trying to replicate exact shipbuilding technology, you should research this.

Stock scarphs, Hook and Butt, and probably more. All of these require precision woodworking to model properly. I know nothing about your model and t what degree of historical accuracy you wish to achieve. If your model is “representative” it’s ok to skip this detail. If you’re trying to replicate exact shipbuilding technology, you should research this.Roger

aper that they were coming to town.

aper that they were coming to town.