Background (continued)

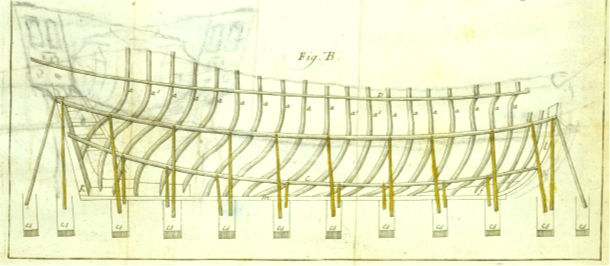

Lavery has noted that one reason seventeenth century plans are incomplete is because they did not show the frames at the ends of a ship. The result was that builders had to interpret the shapes here on their own, and two builders working from the same plans might come up with different shapes. (Lavery 1670, 26) More recently, Endsor (Endsor 2020, pg 208) has described a method of working out the shape of a ship’s aftmost frame (this is called the fashion piece). This method could also work at the bow. It depends on using waterlines, which were not in use in the Sovereign’s time, but the “waterlines” used in the method Endsor describes may have been forerunners of the waterlines later used to describe the shape of an entire ship. Whether this method was used in the early 17th century is not certain. These shipwrights could have shaped the relevant frames in the shipyard using the same methods shipwrights used before plans were drawn.

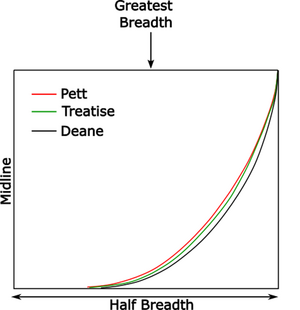

The previous paragraph alludes to another difficulty. Early 17th century plans were drawn using relatively crude methods. This even applies to the Treatise’s methods. It describes the hull’s shape by using only three rising lines three corresponding narrowing lines. The waterlines and buttocks seen on later plans, and that are used to fair a ship during design, had not yet made their appearance. Waterlines are first mentioned in Deane’s Doctrine of 1670 (though not shown on any of his drawings). (Lavery, The Ship of the Line 1984, 13) Buttock lines came into use later. In the meantime, ships had to be faired during construction. This was usually done with an adze.

A third difficulty arises because the radii of the arcs used form the outline of the midship bend were, in the Sovereign’s time, used for all of the frames along the entire ship. The frames at the bow and stern are too compressed to allow this, which caused “bumps” in the hull. Shipwrights probably removed them at the time the ship was built by fixing battens to the hull and trimming off the excess with an adze. (Lavery, Deane's System 1670)

Then, too, the process of ship design was still bound up in the tradition of designing a ship “by eye” and experience so, at first, there was little pressure to draw refined plans. As late as 1665, an overseer of a ship under construction apologized to the Navy Board for the poor quality of the plans he sent them, saying “Would have presented it in better form, but there are no workmen about there who understand the manner of doing it.”(cited in Lavery, (Lavery, The Ship of the Line 1984, 7)) This approach was wasteful, expensive, and produced ships that did not always perform as desired. It was later abandoned.

Another reason for the inaccuracy of 17th century plans is that shipwright’s calculations were often inaccurate. The Treatise often computes numbers to two places to the right of the decimal, giving the impression that 17th shipwrights planned some parts of their ships to an accuracy of at least one1/100 of an inch. This is unlikely. Limits imposed by 17th century construction techniques limited how accurately ships could be built. Accuracy was also limited because ships’ timbers unpredictably shifted during construction (this will be discussed further in the next section), so some crucial dimensions of the ship that was actually built were different from those shown on the plans.

Shipwrights knew this, and this may have contributed to why they did not seek a high degree of accuracy in their computations. The shipwright Jonas Shish computed his narrowing lines at the ship’s aft end to only within a half inch in his 1674 treatise, “The Dimensions of the Modell of a 4th Rate Ship”, and to only to within an inch for its fore end. (Endsor 2020, 117) By modern standards, these are massive computational inaccuracies. However, they could be corrected with an adze, and it was routine to use one on the frames to ensure that the planking ran along a smooth surface. (Fox, Personal Communication)

Greater precision in mathematical results may also have been avoided because performing even simple arithmetic, like multiplication, was tedious. Shipwrights often rounded their numbers, sometimes unpredictably, to simplify their calculations. The Treatise provides an example. Its author reduced the rake of the inner face of his stem by two inches to produce an even number of bends fore of the midship bend. Shipwrights also made mistakes in their calculations, which was easy to do because they had to perform so many calculations. Since there were no rigorous institutionalized review processes, these mistakes often went uncorrected (we will discuss an error that Phineas Pett made when we come to the section on the midship bend). The shipwright William Sutherland may have been taking a jab at Edmund Bushnell when Sutherland said that some shipwrights joined up the arcs on their bends with an adze[1] instead of careful arithmetic

The scale at which shipwrights drew their plans could be another source of error. Plans were usually drawn an 1:48 scale (¼ inch at this scale equals one foot), but some shipwrights used smaller scales. The Treatise’s author cautions against this saying; “there are many good artificers who can plot a ship well and build a ship also, that if their work be compared with their plot you will find them very little agree…” “For if they trust to a small scale, which many times is not above the 10th part of an inch for a foot, divided into 12 parts for every inch, and if they mistake but the 100th part of an inch upon the scale it must needs produce an error of an inch in the ship….”[2]

Drawing itself was non-trivial, particularly when ink was used. Seventeenth century writing and drawing was typically performed using a goose quill, though Queen Elizabeth preferred swan quills. Ink was either iron carbon- or iron gall-based ink. The former was made from soot, and the latter from galls, which are tumor-like growths that result from injury or irritation of a plant. Oak galls were most commonly used. (Leedham-Green 2022) Both types of ink were prone to smear, and both were homemade. Recipes for iron gall ink varied, and were time-consuming. Isaac Newton offers his recipe, in a short piece entitled “To make excellent Ink (Newton c. 1669-1693, 23):

“℞ 1/2 lb of Galls cut in pieces or grosly Beaten, 1/4 lb of Gumm Arabick [gum Arabic is the hardened sap of acacia trees] cut or broken. Put ’em into a Quart of strong beer or Ale. Let ’em stand a month stopt up, stirring them now + then. At ye, end of the month put in ℥1 [℥ is the symbol Newton used for “ounce”] ℥1 1/2 of copperas (too much copperas makes ye ink apt to turn yellow.)[copperas is crystals of hydrated iron sulfate. It is more commonly called “fools gold”] Stir it + use it. Stop it up for some time with a paper prickd full of holes + let it stand in ye sunn. When you take out ink put in so much strong beer + it will endure many years. Water makes it apt to mold. Wine does not. The air also if it stand open inclines it to mold. With this Ink new made I wrote this.”

Even the paper could contribute to inaccuracy. It was rag paper, it was not smooth, and it absorbed ink. To prevent this, it was treated with size, a gelatinous substance made from the hooves and skins of animals, and applied to the surface after the paper had been removed from a mold, rather than mixed with the pulp as it has been in later years. (Leedham-Green 2022) Vellum was the preferred medium on which to draw plans. It was made from animal skins and tended to be greasy. This was combatted by rubbing a coarse substance into it. This substance, called “pounce,” was usually powdered pumice and/or cuttle-fish bone, though crushed egg-shells mixed with powdered incense, and a mixture of alum and resin were also used.

The picture that emerges when we consider the accuracy with 17th century ships were planned and built is one of naval architecture in its infancy. It is limited by its tools, and its traditions. That would change by the century’s end. By this time, shipwrights of one country or another had solved most of the major problems that existed when the century began. Indeed, the 17th century may be the most important century in the entire history of the European sailing warship. I. (Howard 1979, pg 89)

Endsor, Richard. 2020. The Master Shipwright's Secrets. New York: Osprey Publishing.

Fox, Frank. Personal Communication.

Howard, Frank. 1979. Sailing Ships of War 1400 - 1860. New York: Mayflower.

Lavery, Brian. 1670. "Deane's System." In Deane's Doctrine of Naval Architecture, 1670, by Anthony Deane, 128. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press.

—. 1984. The Ship of the Line. Vols. Volume II: Design, Construction and FIttings. Londin: Conway Maritime Press.

Leedham-Green, Elisabeth. 2022. English Handwriting Online 1500-1700. January 4. Accessed January 4, 2023. https://www.english.cam.ac.uk/ceres/ehoc/intro.html.

Newton, Isaac. c. 1669-1693. The Newton Papers, Laboratory Notebook, MS Add. 3975.

[1] Sutherland’s specific quote is “And not to rake in the ashes of some preceding builders that has verified the old proverb, in making the addice [adze] the reconciling mould, there be several at this day that will engage to build a ship with little assistance of such an instrument"(cited in Barker (Barker 1994, pg 40))

[2] All quotations from the Treatise are from a publicly available version in which the English has been modernized, and to which punctuation has been added.

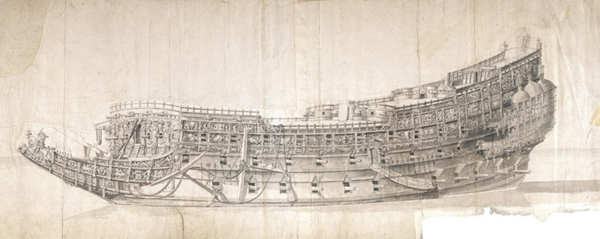

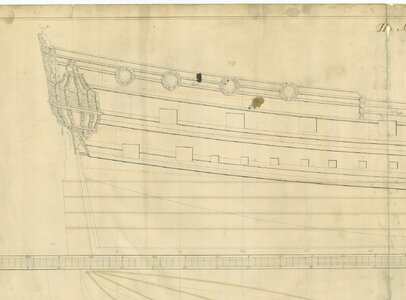

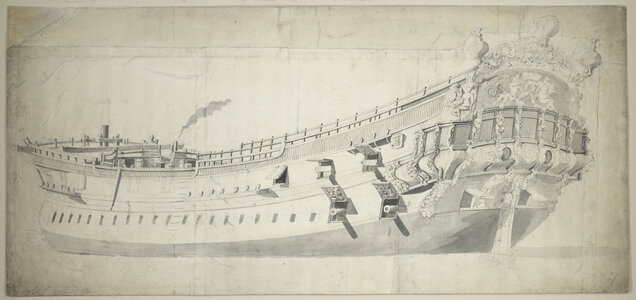

Accuracy of Early 17th Century Ship Plans

A present-day builder (or modeler) attempting to reconstruct a ship from 17th century plans would likely be frustrated. These plans are inaccurate by current standards. They are also incomplete, so building a replica of the Sovereign as originally built would be challenging even if we had the original plans for it. In fact, even a contemporary builder would struggle with this.Lavery has noted that one reason seventeenth century plans are incomplete is because they did not show the frames at the ends of a ship. The result was that builders had to interpret the shapes here on their own, and two builders working from the same plans might come up with different shapes. (Lavery 1670, 26) More recently, Endsor (Endsor 2020, pg 208) has described a method of working out the shape of a ship’s aftmost frame (this is called the fashion piece). This method could also work at the bow. It depends on using waterlines, which were not in use in the Sovereign’s time, but the “waterlines” used in the method Endsor describes may have been forerunners of the waterlines later used to describe the shape of an entire ship. Whether this method was used in the early 17th century is not certain. These shipwrights could have shaped the relevant frames in the shipyard using the same methods shipwrights used before plans were drawn.

The previous paragraph alludes to another difficulty. Early 17th century plans were drawn using relatively crude methods. This even applies to the Treatise’s methods. It describes the hull’s shape by using only three rising lines three corresponding narrowing lines. The waterlines and buttocks seen on later plans, and that are used to fair a ship during design, had not yet made their appearance. Waterlines are first mentioned in Deane’s Doctrine of 1670 (though not shown on any of his drawings). (Lavery, The Ship of the Line 1984, 13) Buttock lines came into use later. In the meantime, ships had to be faired during construction. This was usually done with an adze.

A third difficulty arises because the radii of the arcs used form the outline of the midship bend were, in the Sovereign’s time, used for all of the frames along the entire ship. The frames at the bow and stern are too compressed to allow this, which caused “bumps” in the hull. Shipwrights probably removed them at the time the ship was built by fixing battens to the hull and trimming off the excess with an adze. (Lavery, Deane's System 1670)

Then, too, the process of ship design was still bound up in the tradition of designing a ship “by eye” and experience so, at first, there was little pressure to draw refined plans. As late as 1665, an overseer of a ship under construction apologized to the Navy Board for the poor quality of the plans he sent them, saying “Would have presented it in better form, but there are no workmen about there who understand the manner of doing it.”(cited in Lavery, (Lavery, The Ship of the Line 1984, 7)) This approach was wasteful, expensive, and produced ships that did not always perform as desired. It was later abandoned.

Another reason for the inaccuracy of 17th century plans is that shipwright’s calculations were often inaccurate. The Treatise often computes numbers to two places to the right of the decimal, giving the impression that 17th shipwrights planned some parts of their ships to an accuracy of at least one1/100 of an inch. This is unlikely. Limits imposed by 17th century construction techniques limited how accurately ships could be built. Accuracy was also limited because ships’ timbers unpredictably shifted during construction (this will be discussed further in the next section), so some crucial dimensions of the ship that was actually built were different from those shown on the plans.

Shipwrights knew this, and this may have contributed to why they did not seek a high degree of accuracy in their computations. The shipwright Jonas Shish computed his narrowing lines at the ship’s aft end to only within a half inch in his 1674 treatise, “The Dimensions of the Modell of a 4th Rate Ship”, and to only to within an inch for its fore end. (Endsor 2020, 117) By modern standards, these are massive computational inaccuracies. However, they could be corrected with an adze, and it was routine to use one on the frames to ensure that the planking ran along a smooth surface. (Fox, Personal Communication)

Greater precision in mathematical results may also have been avoided because performing even simple arithmetic, like multiplication, was tedious. Shipwrights often rounded their numbers, sometimes unpredictably, to simplify their calculations. The Treatise provides an example. Its author reduced the rake of the inner face of his stem by two inches to produce an even number of bends fore of the midship bend. Shipwrights also made mistakes in their calculations, which was easy to do because they had to perform so many calculations. Since there were no rigorous institutionalized review processes, these mistakes often went uncorrected (we will discuss an error that Phineas Pett made when we come to the section on the midship bend). The shipwright William Sutherland may have been taking a jab at Edmund Bushnell when Sutherland said that some shipwrights joined up the arcs on their bends with an adze[1] instead of careful arithmetic

The scale at which shipwrights drew their plans could be another source of error. Plans were usually drawn an 1:48 scale (¼ inch at this scale equals one foot), but some shipwrights used smaller scales. The Treatise’s author cautions against this saying; “there are many good artificers who can plot a ship well and build a ship also, that if their work be compared with their plot you will find them very little agree…” “For if they trust to a small scale, which many times is not above the 10th part of an inch for a foot, divided into 12 parts for every inch, and if they mistake but the 100th part of an inch upon the scale it must needs produce an error of an inch in the ship….”[2]

Drawing itself was non-trivial, particularly when ink was used. Seventeenth century writing and drawing was typically performed using a goose quill, though Queen Elizabeth preferred swan quills. Ink was either iron carbon- or iron gall-based ink. The former was made from soot, and the latter from galls, which are tumor-like growths that result from injury or irritation of a plant. Oak galls were most commonly used. (Leedham-Green 2022) Both types of ink were prone to smear, and both were homemade. Recipes for iron gall ink varied, and were time-consuming. Isaac Newton offers his recipe, in a short piece entitled “To make excellent Ink (Newton c. 1669-1693, 23):

“℞ 1/2 lb of Galls cut in pieces or grosly Beaten, 1/4 lb of Gumm Arabick [gum Arabic is the hardened sap of acacia trees] cut or broken. Put ’em into a Quart of strong beer or Ale. Let ’em stand a month stopt up, stirring them now + then. At ye, end of the month put in ℥1 [℥ is the symbol Newton used for “ounce”] ℥1 1/2 of copperas (too much copperas makes ye ink apt to turn yellow.)[copperas is crystals of hydrated iron sulfate. It is more commonly called “fools gold”] Stir it + use it. Stop it up for some time with a paper prickd full of holes + let it stand in ye sunn. When you take out ink put in so much strong beer + it will endure many years. Water makes it apt to mold. Wine does not. The air also if it stand open inclines it to mold. With this Ink new made I wrote this.”

Even the paper could contribute to inaccuracy. It was rag paper, it was not smooth, and it absorbed ink. To prevent this, it was treated with size, a gelatinous substance made from the hooves and skins of animals, and applied to the surface after the paper had been removed from a mold, rather than mixed with the pulp as it has been in later years. (Leedham-Green 2022) Vellum was the preferred medium on which to draw plans. It was made from animal skins and tended to be greasy. This was combatted by rubbing a coarse substance into it. This substance, called “pounce,” was usually powdered pumice and/or cuttle-fish bone, though crushed egg-shells mixed with powdered incense, and a mixture of alum and resin were also used.

The picture that emerges when we consider the accuracy with 17th century ships were planned and built is one of naval architecture in its infancy. It is limited by its tools, and its traditions. That would change by the century’s end. By this time, shipwrights of one country or another had solved most of the major problems that existed when the century began. Indeed, the 17th century may be the most important century in the entire history of the European sailing warship. I. (Howard 1979, pg 89)

References

Barker, Richard. 1994. "A Manuscript on Shipbuilding, Circa 1600, Copied by Newton." The Mariner's Mirror. 80 16-29.Endsor, Richard. 2020. The Master Shipwright's Secrets. New York: Osprey Publishing.

Fox, Frank. Personal Communication.

Howard, Frank. 1979. Sailing Ships of War 1400 - 1860. New York: Mayflower.

Lavery, Brian. 1670. "Deane's System." In Deane's Doctrine of Naval Architecture, 1670, by Anthony Deane, 128. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press.

—. 1984. The Ship of the Line. Vols. Volume II: Design, Construction and FIttings. Londin: Conway Maritime Press.

Leedham-Green, Elisabeth. 2022. English Handwriting Online 1500-1700. January 4. Accessed January 4, 2023. https://www.english.cam.ac.uk/ceres/ehoc/intro.html.

Newton, Isaac. c. 1669-1693. The Newton Papers, Laboratory Notebook, MS Add. 3975.

[1] Sutherland’s specific quote is “And not to rake in the ashes of some preceding builders that has verified the old proverb, in making the addice [adze] the reconciling mould, there be several at this day that will engage to build a ship with little assistance of such an instrument"(cited in Barker (Barker 1994, pg 40))

[2] All quotations from the Treatise are from a publicly available version in which the English has been modernized, and to which punctuation has been added.

Last edited: