WOW TRMEDOUS RESEARCH, AS WITH WALDEMAR, AND OLHA/KORUM THE ONLY INTERESTING THREAD ON SOS. GOD BLESS STAY SAFE ALL DON

-

Win a Free Custom Engraved Brass Coin!!!

As a way to introduce our brass coins to the community, we will raffle off a free coin during the month of August. Follow link ABOVE for instructions for entering.

-

PRE-ORDER SHIPS IN SCALE TODAY!

The beloved Ships in Scale Magazine is back and charting a new course for 2026!

Discover new skills, new techniques, and new inspirations in every issue.

NOTE THAT OUR FIRST ISSUE WILL BE JAN/FEB 2026

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

17th Century Ship Design and the Sovereign of the Seas (1637)

.. the rest of us are chopped liver.WOW TRMEDOUS RESEARCH, AS WITH WALDEMAR, AND OLHA/KORUM THE ONLY INTERESTING THREAD ON SOS. GOD BLESS STAY SAFE ALL DON

I remain completely fascinated by what you are doing, here. BRAVO

BUT BOY YOU SURE HAVE OTHER WITCH IS SO GREATLY NEEDED.. I POSTED SOMETHING ON OLHA/KORUM SITE CONCERNING THIS WHSAQT YOU GUYS ARE DOING YOU, WALDEMMARE, KORUM CONCERNIG SOMETHING THAT I HAVE BEEN LOOKING FOR FOR A LONG, LONG TIME, I DO NOT WANT TO HIJACK YOUR THREAD WILL PM YOU. GOD BLESS STAY SAFE YOU AND YOURS DON

Section III: The Midship Bend

An obviously important question to ask when reconstructing the Sovereign is “What did its midship bend look like?” The answer to this question tells us much about what the rest of the Sovereign looked like. The question is made even more important because, in answering it, we must account for several of this ship’s fundamental dimensions, including its depth and breadth. The present section will account for other dimensions of the Sovereign as well. In the process, we will see that several aspects of this bend are a matter of speculation.Much of the midship bend described in the present section, and most of the arguments for the its shape, are based upon a bend proposed by Frank Fox. I will note my modifications of his bend at the appropriate places below.

The Sweeps

The shape of the midship bend is determined by its number of sweeps (arcs), and their radii. One of the first things we need to decide about the Sovereign’s midship bend is how many sweeps it had.Different ships had different numbers of sweeps. Bushnell’s ship has three, the Treatise’s ship has four, and Deane employs five. We can immediately rule out three sweeps for the Sovereign because the Sergison papers, which record of the number of sweeps Pett originally proposed for this ship, list the sweep at the runghead, the sweep of the futtock, and the sweep at the breadth. The ship would have also had a hollowing (aka toptimber) sweep, which shipwrights usually did not report. These papers thus suggest a total of four sweeps. On the other hand, Pennington describes the sweep at the runghead, the sweep at the right of the mold, the sweep between waterline and breadth, and the sweep above the breadth. His midship bend would also have had a hollowing sweep, bringing the number of sweeps to five.

Pennington’s addition of an “extra” sweep is curious because he was not a shipwright. Merely adding a fifth sweep, not to mention knowing how to compute a radius that allowed this sweep to appropriately fit with the bend’s other sweeps, would likely have been beyond him. It is, therefore, reasonable to suggest that he obtained the radius of his “extra” sweep by modifying a figure provided by Pett, and that Pett’s original figure was not recorded in the Sergison Papers.

There are no data to help us resolve the issue of whether the Sovereign’s midship bend had four or five sweeps. The decision about the number of sweeps the Sovereign’s midship bend had must be based on speculation. The primary argument for five sweeps is that there was something about the Sovereign’s above water shape that was admired and copied in later decades. (Fox, Personal Communication) Its original shape was also thought pleasant enough to retain throughout its several repairs, and even its 1684 rebuild. (Fox, Personal Communication) Thus, a 1687 letter, probably written by (or in consultation with) Robert Lee states that the Sovereign was “kept to same shape with her old timbers.” (cited in Laughton 1932) Adding a fifth sweep also conforms to the preferences of 17th century citizens. They preferred curved shapes, and would have thought a surface with more curvature was more beautiful than one that did not curve as much. The fifth sweep that Pennington describes expands the curvature near the breadth. A ship with only four sweeps would curve less here. It also would not have been distinctive enough to be admired or copied.

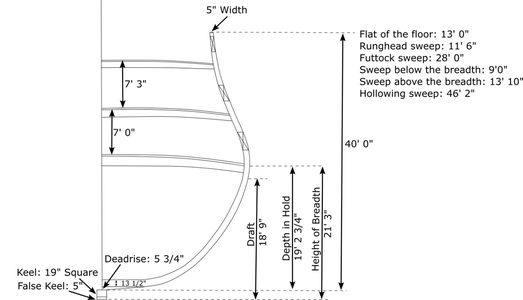

Based on the preceding argument, the current plans use a midship bend with five sweeps based. This is done with the recognition that anyone who chooses to use only four sweeps cannot be proved wrong. Regardless, the radii of the sweeps on the present plans are:

- Sweep at the runghead: 11 feet 6 inches

- Sweep of the futtock: 28 feet.

- Sweep below the breadth: 9 feet.

- Sweep above the breadth: 13 feet 10 inches

- Hollowing sweep: 46 feet 2 inches

Determining the shape of the hollowing sweep is more complicated. The Treatise tells us that a straight timber is “the ordinary,” but adds; “I commend the hollowing post, which is more comely to the eye and more ease to the ship’s side; seeing by tumbling thereof the weight of the ordnance and of the upper work is brought so far into the body of the ship that it is supported without stress, whereas in a straight post they both hang over the side, which is a great burden to it.” Therefore, I used a hollowing post.

The radius of the hollowing sweep varies widely among different published plans for the Sovereign. Perrin, for example (Perrin 1918, xcvii) sets it at 14 feet, while McKay (McKay 2020, 26) places it at 40 feet.[2] I have set it equal to the breadth, which is the Treatise’s a preferred radius, though is author also says we can make it “more or less with a longer or shorter radius.” This is over twice the radius Deane suggests.”[3] The reason for choosing this radius will be discussed further when we discuss the body plan. Suffice it to say here, that the radius I used allows one to use the same sweep along the entire waist (the bends here lie both fore and aft of the midship bend), thus keeping the shape of the upper waist uniform and, in a nod to 17th century aesthetics, keeping the ship “curvier” here.

The present reconstruction makes width of the midship bend at the hollowing sweep’s top follow one of the Treatise’s recommendations. It tells us that the bend should narrow here by “¼ at the least or ⅓ at the most of the ½ breadth” from the maximum breadth[4] The present plans use a narrowing of ¼ the half breadth. A byproduct of this is that it produces the widest upper gun deck that the Treatise allows. Deane would have us bring the toptimber’s head in by 4/6 the floor’s half breadth.[5] This results in an even wider deck. We have already questioned the limited relevance of Deane’s dimensions to the Sovereign, and can extend this by noting that earlier shipwrights believed that keeping the weight of the upper decks’ guns near the ship’s midline increased stability. This thinking changed, so the narrowing was progressively reduced during subsequent years. (Lavery 1984, 25) By 1684, Edward Battine (Battine 1684)[6] would suggest an even wider deck that Deane. Battine puts the “Breadth at ye Toptimber head” at the midship bend as 5/6 the main breadth.

Depth in Hold

The depth in hold is measured from the keel’s top to the height of the breadth. The height of the breadth is the height of the widest part of the midship bend. The breadth’s height was measured from the keel’s bottom. The depth in hold was frequently part of a proportional rule used to determine the dimensions of other parts of a ship, though it could be found from a proportional rule.Pett’s listing tells us that the Sovereign’s depth was 18 feet 9 inches. It is a mistake. It illustrates the effects of the lack of institutionalized quality control methods mentioned earlier.

Understanding why Pett made a mistake requires an understanding of deadrise. It is located at the hull’s bottom, and is where water is collected so it can be pumped out of the ship. [7] The Treatise’s longest passage on the deadrise tells us that:

“You may draw another parallel […?...][8] at 3 or 4 inches distance for the limber holes called a dead rising line; which being taken into the rising for the timbers they shall retain their full depth without any maim by cutting out those holes to convey the water. Some use an unequal dead rising which will do well also, and they draw a straight line from the pitch of the forefoot to the sternpost, allowing one third of the greatest rising upon ⅓ of the keel, which they make more or less as they will have the ship draw more water abaft than afore.”

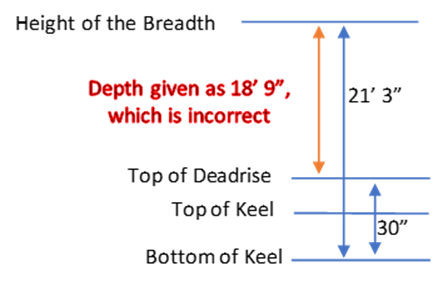

With this information, we can now show Pett’s mistake. He tells us that the height of the breadth was 21 feet 3 inches, and that the top of the deadrise was 30 inches above the keel’s bottom. These dimensions do not fit with Pett’s depth. As shown in Figure 9, the depth that Pett provides is not big enough to run from the height of the breadth down to the keel’s top. What Pett has actually provided is the distance from the height of the breadth to the top of the deadrise. We must therefore find the depth on our own.

Figure 9. Pett’s Erroneous Depth in Hold

Note: The figure is not drawn to scale

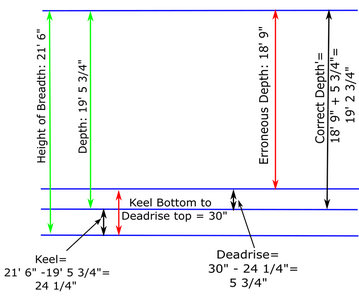

We compute the Sovereign’s true depth in hold in three steps; (1) calculate the keel’s depth, (2) calculate the deadrise’s size, and then (3) calculate the depth in hold (Figure 10 illustrates these steps). We must use some of Pennington’s dimensions to do this because Pett does not give us all the information we need. The reasoning behind using Pennington’s dimensions is that his ship is a derivative of Pett’s. At worst, Pennington’s information gives us the closest approximation of the Sovereign we can get. At best, it provides the exact depth.

The keel’s depth is Pennington’s height of the breadth minus the depth of his ship. He gives the breadth’s height as 21 feet 6 inches, and we previously used Equation 2 to find that its depth was 19 feet 5 ¾ inches. The keel’s height is therefore 24 ¼ inches (when drawing the keel on our plans, we will assume the false keel was 5 inches thick, and the keel was 19 ¼ inches square in cross section).

The deadrise is now its height above the keel’s bottom minus the keel’s depth. Pett gives us the former it is 30 inches. The latter is the depth we just found, 24 ¼ inches. The Sovereign’s deadrise is thus 5 ¾ inches.

We can now find this Sovereign’s correct true depth. This equals the erroneous depth in hold that Pett provides, 18 feet 9 inches, plus the deadrise, 5 ¾ inches. The depth in hold is thus 19 feet 2 ¾ inches.[9]

Figure 10. Calculating Depth in Hold, the Keel’s Depth, and Deadrise

Note: Green arrows indicate information from Pennington, red arrows indicate information from Pett, and black arrows indicate calculated dimensions. The figure is not drawn to scale

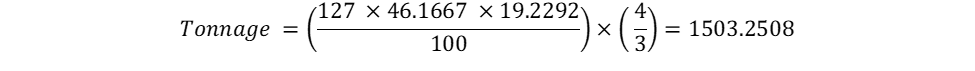

The Sovereign’s Designed Tonnage

We previously found that the Sovereign’s tonnage, as built, was 1522. However, this figure results from measurements of the ship that was taken after it “fell out.” Of more interest here is its tonnage as designed. The Admiralty, on March 7, 1635, told Pett to build a “new great ship” of 1500 tons. (Perrin 1918, xci) Therefore, if the previous dimensions are correct, we would expect them to yield a tonnage close to this figure.Pett tells us that the Sovereign’s keel was 127 feet long, and, its breadth was 46 feet 2 inches. We have just computed its depth as 19 feet 2 ¾ inches. We can now insert these figures into Equation 1 to calculate its designed tonnage. The result is:

This rounds to 1503 tons. That it is so close to the requested tonnage lends credence to the depth in hold used in the present reconstruction.

The Deck Beams

The deck beams’ heights and cambers not only help us draw the midship bend, they are also used to place the decks and gun ports along the entire ship.The simplest way to locate the Sovereign’s deck beams is to begin by finding the height of the lower gun deck’s beam at the ship’s side. The lower, upper, and middle gun deck beams in the present reconstruction closely follow the dotted lines shown in the Pett painting. We are not given any contemporary, quantitative information about this, though a dotted line on the Pett painting gives us a general idea of where it was. The beam at the ship’s side is most realistically placed so that its top at the height of the breadth. It would certainly not be lower, and placing it higher puts the gun ports very close to the deck.[10] This position differs from that described in the Treatise, which would have us put the beam’s bottom here.

Deck Cambers

Cambered decks are higher along the ship’s midline than at its sides. Cambering helps water drain off the decks. Deck cambers in the Sovereign’s time progressively decreased as we move to increasingly higher decks. This pattern was reversed by 1660. Now, a ship’s lowest gun decks had a camber of seven inches, and the cambers progressively increased as we moved upwards. (Fox, Personal Communication).The cambers we choose for the Sovereign’s decks are surprisingly impactful. They affect the precise heights at which we place the gun ports along the ship’s sides and this, in turn, affects how we draw the wales, which affects how we draw the quarter galleries. If our cambers are incorrect, these other aspects of the Sovereign will not align properly. These "other aspects" therefore impose what I will call secondary constraints on the cambers we can use.

Information given by the Pett painting imposes a primary constraint on the cambers we can use for the Sovereign’s decks. It shows us that the vertical spacing between the gun deck’s beams was equal at the ship’s side. An additional primary constraint is added because the deck cambers must decrease as we move upwards. When we examine the effect of these primary constraints on the cambers, we find, for example, that although cambers shown in the leftmost column of Table 3 correctly decrease as we move upwards, the vertical spacing between them is not equal. Therefore, this combination of cambers is not allowable. This is one of many camber patterns that are not allowable.

Table 3. Examples of Allowable and Unallowable Gun Deck Cambers

Unallowable Pattern | Allowable Pattern #1 | Allowable Pattern #2 | Allowable Pattern #3 | Allowable Pattern #4 | Allowable Pattern #5 | |

Lower Gun Deck | 18 | 18 | 18 | 16 | 14 | 7 |

Middle Gun Deck | 14 | 12 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 9 |

Upper Gun Deck | 10 | 8 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 13 |

Note: All cambers are expressed in inches. The rightmost pattern resembles one that might have been used in the latter part of the 17th century. Allowable and unallowable patters were determined in conjunction with the heights deck heights that Pett provides (see Table 4) and the thickness of the planking (see below).

Table 3 also shows us that the primary constraints placed on the cambering do not yield a single set of cambers for the Sovereign’s decks. Table 3 shows several allowable patterns, including one (pattern #5) that is like that of later ships. Patterns #1 and #2 are of the most interest because the 18-inch cambers of their lower gun decks are derived from the Treatise’s dimensions. The present reconstruction uses the first pattern because the middle gun deck’s camber is also loosely related to the Treatise’s dimensions, [11] and because it seemed to more readily lead to wales, rails, and quarter galleries like those seen in contemporary representations of the Sovereign than did Pattern #2. The camber for the Sovereign’s upper gun deck, 8 inches, is the only allowable camber if the cambers of the lower and middle gun decks are 18 and 12 inches, respectively.

I have made the cambers of all the upper decks 6 inches. This equals the cambering of the half deck on the Treatise’s ship.

The Beams’ Thicknesses

Deck beams were thickest at the lowest gun deck, and became progressively thinner on increasingly higher decks. Their middles were also thicker than their sides.The thicknesses of the Sovereign’s beams are a matter of speculation. The beam on the lowest gun deck of the Treatise’s ship is “16 or 18 inches deep in the middle.” I have used the thicker of the Treatise’s recommendations because the guns on the Sovereign’s lowest deck were larger than those on the Treatise’s ship. The next deck on the Treatise’ ship had a beam that was “12 or 14 inches deep in the middle”, and I have used the thicker of the two for the Sovereign’s middle gun deck from the bow to 5 feet aft of the fore end of the lower quarter gallery’s extension.[12] This deck’s beams become one foot thick aft of this. Reducing their size helps to create room for the tiller, which runs under this deck. This maneuver is acceptable because the aftmost ports on the Sovereign’s side were usually unarmed (this will be further discussed when we reach the section on the Sovereign's guns) so this part of the deck bore less weight than the rest of it. The beams of the forecastle, half deck, and quarter deck are all nine inches thick in their middles. This corresponds to the Treatise, which tells us that its half deck beam was “9 or 10 inches deep in the middle.” The beams for the roundhouse are nine inches thick in their middles. The Treatise’s ship has no corresponding deck.

The beams taper as they travel towards their ends at the side of the ship. The current plans use the Treatise’s suggestion that the thickness of the beams at the side of the ship should be ⅔ of their thickness at the middle.

Deck Planking

I have used planking thicknesses of four inches for the lower gun deck, three inches for the middle gun deck, and two inches for the upper gun deck. Four inches is also the thickness that the Treatise and Deane used for their gun lowest decks.The planking on all the remaining decks is two inches thick. The Treatise’s description of the planking on its other decks is garbled, but it appears to make its upper gun deck three inches thick, and the decks above it 1 ½ or two inches thick, sometimes planked “with Prussia deals[13] for lightness sake.”

Gun Deck Heights

In the present subsection, the heights of the gun decks refer to the heights of the tops of their planking at the ship’s midline. Here, we can use information that Phineas Pett provides about the height of one deck above another. The deck heights he reports, and that are used in the current plans, are shown in Table 4. Deck heights at the ship’s side, which accounts for their cambers and planking thicknesses, are also provided in the table.Table 4. Heights of the Sovereign’s Gun Decks

Deck | Plank-to-Plank Height above Deck Below (feet)* | Height of the Deck’s Center (feet from keel top)** | Deck Height at Ship’s Side (feet from keel top)** |

Lower Gun Deck | Not Applicable | 21.06 | 19.56 |

Middle Gun Deck | 7.00 | 28.31 | 27.31 |

Upper Gun Deck | 7.25 | 35.73 | 35.06 |

**Deck height refers to the height at the top of the deck’s planking.

The Final Midship Bend

The midship bend used in the present plans is shown in Figure 11.Figure 11. The Midship Bend

Notes on Figure 11

Both Fox’s and the present midship bend differ from the Treatise, which says that the bend’s top should be twice the depth. The top of the present midship bend is 40 feet from the keel’s top. This places it at a height equal to twice the depth plus 18 ½ inches. Frank Fox’s bend is twice the depth plus about 10 inches. The difference between the height of the present bend and Fox’s bend is mostly due to differences in the cambers of the middle and upper gun decks.Although the midship bend on the current plans is higher than suggested by the Treatise, it is reasonable to suggest that a greater proportion of the Sovereign’s midship bend was further above the water than seen in 2-decked ships. This increased proportion may have been what alarmed the Masters of Trinity house, who noted that the ports on this ship would have to be five or more feet above water, which would ultimately make “the third tier lie at a height as not to be serviceable.”

It is indeed true that Pett designed the Sovereign so that its ports were five feet above water. However, this was when the ship was provisioned “with four months victuals.” Under this condition, Pett estimated that the ship’s draft would be 18 feet 9 inches, as measured from the keel’s bottom. However, Pett also tells us that the designed “[d]raught of water from the breadth to the lower edge of the keele” was 21 feet 3 inches, and this is presumably the draft of the fully loaded ship. (Ferriero 2007, 196)

Now consider the Newton Manuscript’s recommendation, which is that “The height of the ship above water must be in proportion unto that part of the ship under water & the height of the ship in the mid-ship must not exceed the depth under water.” The Sovereign’s height when carrying “four months victuals” should, therefore, be no more than 37 ½ feet above the keel’s bottom, which the present midship bend exceeds. However, when fully loaded, the bend’s height can be 42 feet 7 ¾ inches. The present bend is 42 feet ¼ inch from the keel’s bottom, so it is within this maximum.

Although the height of the present midship bend is not as extreme as the Treatise’s recommendations would lead us to believe, the Sovereign may have been top heavy when not fully loaded. This explains the comment, made in 1651, that the ship needed to be made “more serviceable then now shee is.” This difficulty may have persisted, even after the Sovereign was cut down during its first repair. Accordingly, its draft was increased during the 1659-1660 repair. This would allow the ship to carry more ballast.

[1] Arriving at both the sweep of the breadth proposed here, and at Pennington’s proposed sweep, requires rounding the result of multiplying 3/10 the breadth times the breadth to the nearest inch. The results of Pett’s and Pennington’s original computations for the radii of all their sweeps may also been rounded.

[2] The radius of the hollowing sweep suggested by Frank Fox is 13 feet 10 inches.

[3] Deane suggests a radius of 17/18 of the half breath, which is about 21 feet 9 ½ inches on the Sovereign.

[4] The Treatise’s author is discussing tumblehome, though he does not use the term. Tumblehome is a measurement of how much narrower the ship’s side is at its top than at its breadth. The author’s discussion directly applies when the toptimber rising line is at the timberheads of the midship bend. We will see later that the current plans use a toptimber rising line that lies above the timberheads. Therefore, the discussion above is a simplification.

[5] This fraction can be reduced to ⅔, but Deane does not do this.

[6]A copy of Battine’s book can be downloaded at https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/17268860

[7] Water gets into the deadrise through drain holes in the ceiling, which lies above the deadrise. These holes are called limber holes. These holes sometimes became clogged with waste and debris. When this happened, they were cleaned with limber ropes. These were ropes that were laid out through the holes an along the keelson. They were pulled back and forth in the same manner that someone uses dental floss. (Simmons 1985, 10)

[8] There are words missing from the Treatise here.

[9] The depth in hold on the first rate described by William Keltridge is 18 feet 3 inches.

[10] Pett tells us that the port sills were five feet from the water at the midship bend. This fixes their height, so any movement of the beam only changes the ports’ height above the deck. If we were to move the beam’s bottom up to the height of the breadth, the ports on the lower gun deck would only be 9 inches above the deck.

[11] The Treatise recommends 14 inches of camber for the lower gun deck of its ship, which is 36 feet broad. This equals 0.3889 inches of camber per foot of breadth. Multiplying this by the Sovereign’s breadth of 46 feet 2 inches yields 17.95 inches for the Sovereign’s camber at the midship bend. We can round this to 18 inches. The camber of the middle gun deck is similarly computed. Thus, starting with the 9-inch camber on the Treatise’s ship, we compute a camber of 11.54 inches for the Sovereign. This is rounded to 12 inches

[12] This is at aft bend 28. The numbering of the bends will be discussed later.

[13] In the 17th century, “deal” probably referred to a slice of wood sawn from a log of timber, and usually more than seven inches wide, and not more than three inches thick. It was typically pine or fir.

References

Anderson, R C. 1919. "The Midship Section of the Sovereign." The Mariner's Mirror. 5 125-126.Battine, Edward. 1684. The method of building, rigging, appareling and furnishing........

Ferriero, Larrie D. 2007. Ships and Science. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Fox, Frank. n.d. "Personal Communication."

—. n.d. "Personal Communication."

Laughton, L. C. Carr. 1932. "The Royal Sovereign, 1685." The Mariner's Mirror 18 (2): 138-150.

Lavery, Brian. 1984. The Ship of the Line. Vols. Volume II: Design, Construction and FIttings. Londin: Conway Maritime Press.

McKay, John. 2020. Sovereign of the Seas 1637. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Seaforth Publishing.

Perrin, W G. 1918. The Autobiography of Phineas Pett. The Naval Records Society.

Simmons, Joe John. 1985. The Development of External Sanitary Facilities Aboard Ships of the FIfteenth to Nineteenth Centuries (Thesis). College Station, TX: Texas A&M University.

Last edited:

Hi Charlie,

I love your research an indepth posts about this topic.

Have been looking for the Sergison papers showing the mid ship bend sweep radii but can't find anything.

Septhon reports them differently as well the table in Pett's autobiography.

Both these state runghead 11', futtock 31', below breadth 10' and above 14'.

Sure you know these and I was wondering what is the reason for selecting the other values from Sergison.

I love your research an indepth posts about this topic.

Have been looking for the Sergison papers showing the mid ship bend sweep radii but can't find anything.

Septhon reports them differently as well the table in Pett's autobiography.

Both these state runghead 11', futtock 31', below breadth 10' and above 14'.

Sure you know these and I was wondering what is the reason for selecting the other values from Sergison.

Very interesting read.

Thank you for posting.

Thank you for posting.

- Joined

- Jun 4, 2024

- Messages

- 66

- Points

- 68

Hi Maarten;

I will back Charlie up on this as being quite correct with his radii. His first reference given above refers to vol V of the Mariners Mirror, where RC Anderson refers to sizes given in the Sergison Papers, as 'the dimensions of the Sovereign'. These are a repeat of the sizes given in the first list of sizes in Pett's Autobiography (which Anderson does not list again in his note) but with the addition of the sweep radii used by Charlie above, which Anderson does give.

Perrin's midship section is erroneous, as is his use of the second set of dimensions given in the Pett autobiography.

Ratty

I will back Charlie up on this as being quite correct with his radii. His first reference given above refers to vol V of the Mariners Mirror, where RC Anderson refers to sizes given in the Sergison Papers, as 'the dimensions of the Sovereign'. These are a repeat of the sizes given in the first list of sizes in Pett's Autobiography (which Anderson does not list again in his note) but with the addition of the sweep radii used by Charlie above, which Anderson does give.

Perrin's midship section is erroneous, as is his use of the second set of dimensions given in the Pett autobiography.

Ratty

Last edited:

Hi Ratty,Hi Maarten;

I will back Charlie up on this as being quite correct with his radii. His note [8] refers to vol V of the Mariners Mirror, where RC Anderson refers to sizes given in the Sergison Papers, as 'the dimensions of the Sovereign'. These are a repeat of the sizes given in the first list of sizes in Pett's Autobiography (which Anderson does not list again in his note) but with the addition of the sweep radii used by Charlie above, which Anderson does give.

Perrin's midship section is erroneous, as is his use of the second set of dimensions given in the Pett autobiography.

Ratty

Thx for your feedback.

Is this mariners mirror still available as it is from the early 1900's. Have been looking for these but can't find them.

Hi Maarten,

Well, to be honest with you, I could not find where Sephton listed the sweeps, but then, I have not studied his book thoroughly. My guess is that he is reporting Pennington's figures. I suggest this because in the table on page 196 of his book, he characterizes Pett's dimensions as the "Initial Proposal" and Pennington's as the "Final Proposal." Note that a previous post of mine showed that Pennington's dimensions could not have been used, so this is an error by Sephton.

The sweeps in the Sergison papers are those used on the Sovereign. You can get the Mariner's Mirror article (which is a note, rather than a full article) in question. It is at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/00253359.1919.10654870?needAccess=true and it will cost $53.

As a side note, Septhon's book appears to contain many errors. Indeed, it appears to be the source of some common misconceptions about this ship. I've already mentioned his recommendation of the "reconstruction draught" and will discuss a few more later, though I will not specifically cite his book when I do so.

As another side note, I will be making some VERY controversial statements about this ship beginning a few posts from now.

Well, to be honest with you, I could not find where Sephton listed the sweeps, but then, I have not studied his book thoroughly. My guess is that he is reporting Pennington's figures. I suggest this because in the table on page 196 of his book, he characterizes Pett's dimensions as the "Initial Proposal" and Pennington's as the "Final Proposal." Note that a previous post of mine showed that Pennington's dimensions could not have been used, so this is an error by Sephton.

The sweeps in the Sergison papers are those used on the Sovereign. You can get the Mariner's Mirror article (which is a note, rather than a full article) in question. It is at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/00253359.1919.10654870?needAccess=true and it will cost $53.

As a side note, Septhon's book appears to contain many errors. Indeed, it appears to be the source of some common misconceptions about this ship. I've already mentioned his recommendation of the "reconstruction draught" and will discuss a few more later, though I will not specifically cite his book when I do so.

As another side note, I will be making some VERY controversial statements about this ship beginning a few posts from now.

- Joined

- Jun 4, 2024

- Messages

- 66

- Points

- 68

Hi Maarten;

Further to Charlie's answer above, and your question, volume V is available second hand very rarely. You could pay for access to Taylor and Francis, but it will not tell you anything which has not already been said, as the information given in Anderson's note is limited. The dimensions are available in the NRS volume for 1918, the autobiography of Phineas Pett, which is easier to find secondhand. All that is missing in this latter volume are the radii of the three sweeps which Charlie has used, and which are given in the Sergison Papers (Anderson did not specify which of the many volumes it was in)

Charlie is also absolutely correct about Sephton's book. It contains quite a few errors and omissions, and a further drawback with it is that the black and white illustrations are of very poor quality.

Ratty

Further to Charlie's answer above, and your question, volume V is available second hand very rarely. You could pay for access to Taylor and Francis, but it will not tell you anything which has not already been said, as the information given in Anderson's note is limited. The dimensions are available in the NRS volume for 1918, the autobiography of Phineas Pett, which is easier to find secondhand. All that is missing in this latter volume are the radii of the three sweeps which Charlie has used, and which are given in the Sergison Papers (Anderson did not specify which of the many volumes it was in)

Charlie is also absolutely correct about Sephton's book. It contains quite a few errors and omissions, and a further drawback with it is that the black and white illustrations are of very poor quality.

Ratty

Last edited:

- Joined

- Oct 24, 2022

- Messages

- 31

- Points

- 48

Thank you very much for the fantastic informations!

I would be very interested in knowing what some of these errors and omissions are. When gathering research sources, it is far more work to sift through and figure out what is accurate and what is not in the sources than it is to build the model ship itself. Those of you who have done this groundwork would be of great benefit to us builders by posting these details on the forum, and we who strive to make accurate models would be eternally grateful. Thanks to CharleyT for helping us out with some of this hard to find data and his personal research interpretations in this thread.Hi Maarten;

Further to Charlie's answer above, and your question, volume V is available second hand very rarely. You could pay for access to Taylor and Francis, but it will not tell you anything which has not already been said, as the information given in Anderson's note is limited. The dimensions are available in the NRS volume for 1918, the autobiography of Phineas Pett, which is easier to find secondhand. All that is missing in this latter volume are the radii of the three sweeps which Charlie has used, and which are given in the Sergison Papers (Anderson did not specify which of the many volumes it was in)

Charlie is also absolutely correct about Sephton's book. It contains quite a few errors and omissions, and a further drawback with it is that the black and white illustrations are of very poor quality.

Ratty

- Joined

- Jun 4, 2024

- Messages

- 66

- Points

- 68

Hi Kurt;

To describe all the errors and misconceptions would take a long list. The book is informative, certainly, but reading it is a succession of disappointments at the number of demonstrably wrong statements and un-verified assumptions. Sephton does not give an authoritative source for many of his assertions, so we have no way of knowing if he is reporting a contemporary opinion or fact, or his own suppositions.

Charlie's work above is far more reliably based on research into the evidence, and he is certainly using the correct set of dimensions and sweep radii for this ship. Anderson's note with these sweep dimensions is not very well known, I suspect. Without access to an index of early Mariners Mirror volumes it is difficult to find.

Ratty

To describe all the errors and misconceptions would take a long list. The book is informative, certainly, but reading it is a succession of disappointments at the number of demonstrably wrong statements and un-verified assumptions. Sephton does not give an authoritative source for many of his assertions, so we have no way of knowing if he is reporting a contemporary opinion or fact, or his own suppositions.

Charlie's work above is far more reliably based on research into the evidence, and he is certainly using the correct set of dimensions and sweep radii for this ship. Anderson's note with these sweep dimensions is not very well known, I suspect. Without access to an index of early Mariners Mirror volumes it is difficult to find.

Ratty

A long list perhaps. I'd be content with even a short list.Hi Kurt;

To describe all the errors and misconceptions would take a long list. The book is informative, certainly, but reading it is a succession of disappointments at the number of demonstrably wrong statements and un-verified assumptions. Sephton does not give an authoritative source for many of his assertions, so we have no way of knowing if he is reporting a contemporary opinion or fact, or his own suppositions.

Charlie's work above is far more reliably based on research into the evidence, and he is certainly using the correct set of dimensions and sweep radii for this ship. Anderson's note with these sweep dimensions is not very well known, I suspect. Without access to an index of early Mariners Mirror volumes it is difficult to find.

Ratty

- Joined

- Jun 4, 2024

- Messages

- 66

- Points

- 68

Hi Kurt;

That would mean re-reading Sephton's book, which is rather an ordeal. I have already read it twice, and that is as much as I can bear. His style of writing does not flow smoothly, and most of the illustrations are of poor quality. I look upon Sephton's book as a source of some information about her, but not as a source for serious research, due to his lack of references. His book is more a guide to what information might exist somewhere, waiting to be located again, which Sephton presumably saw but does not give a reference to help locate.

That would mean re-reading Sephton's book, which is rather an ordeal. I have already read it twice, and that is as much as I can bear. His style of writing does not flow smoothly, and most of the illustrations are of poor quality. I look upon Sephton's book as a source of some information about her, but not as a source for serious research, due to his lack of references. His book is more a guide to what information might exist somewhere, waiting to be located again, which Sephton presumably saw but does not give a reference to help locate.

I understand, having read Sephton thoroughly myself. The illustrations in my electronic Kindle copy are worthlessly blurry. I was not looking for a comprehensive list, just some of the details off the top of your head, because anything is much better than nothing. For as long as Sephton researched the Sovereign, you would think more of it would be backed up by reliable sources and accurate.Hi Kurt;

That would mean re-reading Sephton's book, which is rather an ordeal. I have already read it twice, and that is as much as I can bear. His style of writing does not flow smoothly, and most of the illustrations are of poor quality. I look upon Sephton's book as a source of some information about her, but not as a source for serious research, due to his lack of references. His book is more a guide to what information might exist somewhere, waiting to be located again, which Sephton presumably saw but does not give a reference to help locate.