-

Win a Free Custom Engraved Brass Coin!!!

As a way to introduce our brass coins to the community, we will raffle off a free coin during the month of August. Follow link ABOVE for instructions for entering.

-

PRE-ORDER SHIPS IN SCALE TODAY!

The beloved Ships in Scale Magazine is back and charting a new course for 2026!

Discover new skills, new techniques, and new inspirations in every issue.

NOTE THAT OUR FIRST ISSUE WILL BE JAN/FEB 2026

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

17th Century Ship Design and the Sovereign of the Seas (1637)

- Joined

- Jun 4, 2024

- Messages

- 66

- Points

- 68

Hi Bela;

That is exactly Charlie's point, although he gives a difference of 0.07. The desired unit of room and space is 30". However, the overall length cannot be divided equally by this. The difference is however, very small, and can easily be removed by rounding the number of bends from 37.07 to 37.

This was the contemporary solution, and has been followed by Charlie. As there is a difference, he must mention it, and describe how it was then removed. Thereafter, all calculations are based on a room and space of 30".

Ratty

That is exactly Charlie's point, although he gives a difference of 0.07. The desired unit of room and space is 30". However, the overall length cannot be divided equally by this. The difference is however, very small, and can easily be removed by rounding the number of bends from 37.07 to 37.

This was the contemporary solution, and has been followed by Charlie. As there is a difference, he must mention it, and describe how it was then removed. Thereafter, all calculations are based on a room and space of 30".

Ratty

Last edited:

- Joined

- Jun 4, 2024

- Messages

- 66

- Points

- 68

Hi Bela;

You are correct in that the 0.07 refers to the number of bends, but it also relates to the measurement between them as well.

To be clearer, the 0.07 is a fraction of the 30" unit, and is therefore 0.07 of 30, which is 7 hundredths of 30, which is 0.3 inches x 7 = 2.1 inches. This is the difference between the number of bends (37) x 30", and the overall length of the space to be filled (37.07 x 30")

This difference of 2.1" only occurs once, and as this is a small proportion of the 30" unit, the overall number of bends (which is what Charlie is trying to find here) can safely be rounded down to 32. If the difference had been more than 50 hundredths, the number of bends would have been rounded up to become 33.

Ratty

You are correct in that the 0.07 refers to the number of bends, but it also relates to the measurement between them as well.

To be clearer, the 0.07 is a fraction of the 30" unit, and is therefore 0.07 of 30, which is 7 hundredths of 30, which is 0.3 inches x 7 = 2.1 inches. This is the difference between the number of bends (37) x 30", and the overall length of the space to be filled (37.07 x 30")

This difference of 2.1" only occurs once, and as this is a small proportion of the 30" unit, the overall number of bends (which is what Charlie is trying to find here) can safely be rounded down to 32. If the difference had been more than 50 hundredths, the number of bends would have been rounded up to become 33.

Ratty

Last edited:

Sorry, hit the post button above before finishing this post.I dispense with the usual system of identifying the bends using letters or symbols because doing so is cumbersome for a ship with as many bends as the Sovereign had.

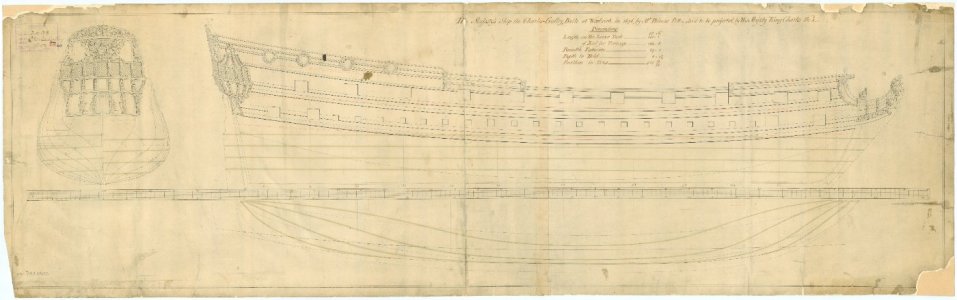

You are not alone Charlie. The below is one example. It is the Charles Galley 1676 and the stations are numbered from 1 aft to 124 forward. No letters are used. It is not the best resolution in the first pic, but the second is the forward portion where you can see the stations are numbered, not lettered.

Allan

You are right, the effect on construction would have been small. However, these small numbers had a massive effect on the mathematics behind computing the rising and narrowing lines. Incorporating tractions are decimals really slowed things down. For example, the steps used to multiply two numbers together were different, and more cumbersome than the steps we now use (see, for example https://www.emmaths.com.au/blog/a-b...he 17th century, the,every digit in the other). Shipwrights rounded numbers to speed things up, and to avoid the errors inherent in performing such a task. Multiplication was so tedious that John Napier "invented" logarithms in the early 17th century to help speed it up. In his words, multiplication required a “tedious expenditure of time” and was subject to “slippery errors."ok, I think we mean the same thing.

However, these minimal deviations have no significance in real construction

I see that it is time for me to read the treatise again.You are right, the effect on construction would have been small. However, these small numbers had a massive effect on the mathematics behind computing the rising and narrowing lines. Incorporating tractions are decimals really slowed things down. For example, the steps used to multiply two numbers together were different, and more cumbersome than the steps we now use (see, for example https://www.emmaths.com.au/blog/a-brief-history-of-multiplication-algorithms#:~:text=In the 17th century, the,every digit in the other). Shipwrights rounded numbers to speed things up, and to avoid the errors inherent in performing such a task. Multiplication was so tedious that John Napier "invented" logarithms in the early 17th century to help speed it up. In his words, multiplication required a “tedious expenditure of time” and was subject to “slippery errors."

years ago I tried to recreate the method of the treatise in a reconstruction. As I recall, the inward and upward curvatures depend on the frame number, not on their distance.

but of course my memory could be deceiving me.

As an FYI, I made a couple of small changes the the section on the sternpost. I've increased its true height to 28 feet 10 inches (its measured height at the wing transom remains at 25 feet), and increased the helm port transom's depth to 14 inches.

Section IV: The Sheer Plan (continued)

The Decks

Nomenclature

Different sources use different terms to describe the Sovereign’s decks. I will refer to the three gun decks as the lower, middle, and upper gun decks. This is less confusing than the names used at the time. For example, the lower gun deck was known as the orlop, but later, “orlop” came to refer to a deck that was below the lower gun deck. Phineas Pett’s list is also a bit confusing. It refers to the middle gun deck as the “first deck,” and the upper gun deck as the “second deck.” The term “gun deck” was also applied to the lower gun deck, but since the Sovereign had 3 gun decks, “gun deck” is not specific. I use the term “gun deck” only when it is obvious that I am referring to the lower gun deck.I continue to call the forecastle just that. Just behind the forecastle lies the exposed upper gun deck, which is the waist. Moving from fore to aft, the aft upper decks are the half deck (it was probably called this because it covered about half the ship), the quarterdeck (it covered about a quarter of the ship), and the roundhouse. Pett also uses the first two terms to describe the foremost two upper decks, and Thomas Heywood, in 1637, followed this terminology in describing the Sovereign when he said that “She hath … a Fore-Castle, an halfe Decke, a quarterdecke, and a round-house.” William Marshall, who apparently never saw the Sovereign, apparently misunderstood the term “roundhouse.” He actually drew a round house on it in 1637 (see Figure 25).

Figure 25. Marshall’s 1637 Depiction of the Sovereign of the Seas

Section IV: The Sheer Plan (continued)

Overview of The Gun Decks

There were two ways to design early 17th century gun decks. The first was to make them suddenly drop to a lower height as they approached the stern. This sudden drop was known as a fall. The second way was to omit the fall and make the surface of the decks “smooth.” These decks were called flush decks.The Treatise’s author prefers decks with falls, arguing that such decks do not cut the wales, and that they give “a greater strength to the ship than a flush deck.” His preference was not universal. Although the author of the Newton Manuscript appears to default to decks with a fall, he also states that “if your work will give it leave it is good to lay the orlope without fales [falls] ffor it is a great strength to the ship for the orlope to go flish [flush] forth & aft, & besides it will be very commodious for ye use of ye ordinance.” Sir Henry Mainwaring adds that “the best contriving of a man-of-war is to have [the decks flush and to have] all her ports on that deck on an equal height so as that every piece may serve any port: the reasons are, for that the decks being flush, men may pass fore and aft with much more ease for the delivering powder and shot, or relieving one another, but chiefly for that if a piece or two be dismounted by shot in any place where there is a fall, another cannot be brought to supply its place …” (Mainwaring 1922, 139)

The Sovereign’s decks were flush. In his letter to the King, Pett tells us that “all the decks” were “flush fore and aft.” The dotted lines that portray the deck beams in the Pett painting also suggest they were flush. Heywood’s 1637 brochure also tells us that the Sovereign “hath three flush Deckes…” (Heywood 1637) This description confirms that the Sovereign’s gun decks were built as Phineas Pett planned. It disagrees with the way the decks’ are portrayed on some existing plans.

That the decks were flush does not mean they were flat. The Treatise’s author tells us this by saying “if you will have it [the deck] flush fore and aft, let it rise 2 foot more above the swimming line both fore and aft than it [lies] in the midships….” Avoiding decks that are entirely flat is desirable. Water drains more easily off sloping decks.

Sometimes, part of the deck was allowed to be flat. Shipwrights drew gun decks on their plans using a bow, so the decks formed an arc. The increase in this arcs’ heights from one bend to the next could be less than contemporary building tolerances. The deck was often flattened amidships as a result.

The Lower Gun Deck

The Course of the Sovereign’s Lower Gun Deck

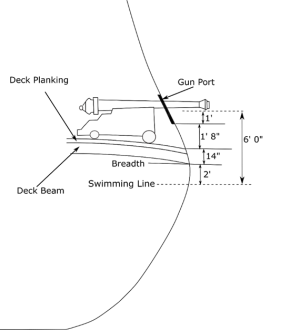

Positioning the lower gun deck requires us to consider the swimming line’s height. More specifically, we need to consider how far above the water the gun ports should be. As Sir Anthony Deane put it, “As to the gun deck, I am ruled by my water line, which I have taken such care to assign well, and, being assured of the ship’s going no deeper into the water, I consider how high my guns ought to be…” The reason for this is obvious; if the ports were too close to the water, the ship could sink. In fact, the introduction of gun ports in the early 1500’s may have been the main reason shipwrights began calculating ship’s drafts in the first place. (Ferriero 2007, 196)The Treatise’s author is more specific. When he tells us how to consider the swimming line at the midship bend, we are to “Let the lower edge of the beam for the orlop[1] [be] pitched at the breadth, so it shall be pitched two feet above the water line. The deck will be 14 inches, the lower edge of the port 1 foot 8 inches above the deck, and the mouth or muzzle of the pieces near a foot. In all, from the ordnance to the water will be 6 foot thereabouts.” Figure 26 depicts this arrangement.

Figure 26. The Treatise’s Deck Placement

Once we know the deck’s height at the midship bend, we need to find how much it should rise fore and aft of this bend. Shipwrights’ views on this varied, leading to variation in how the decks rose with respect to the keel, and with respect to the waterline.

Deane says “… I set off in the midships from my water-line 18 inches, and afore and abaft 2 feet 10 inches, by which my deck hangs 16 inches.” This instruction seems to tell us that he sets his deck’s height by considering the waterline at the midship bend, and then makes it rise 16 inches to the bow and stern. His drawings support this interpretation. They show the deck’s fore and aft ends the same height above the keel. This places the deck’s aft end closer to the water than its fore end.

The Treatise’s author would have us put both ends of a flush deck two feet further from the water than at the midship bend. Since the Treatise does not provide clear instruction about how to draw the swimming line, it is difficult to determine exactly how much the deck on its ship rose with respect to the keel. However, since ships drew more water at the stern than the bow, the Treatise’s deck, and therefore its ports, are closer to the keel at the bow than at the stern.

Bushnell’s deck is different. Its fore end is closer to the water than its aft end so, as Bushell says, the ports are “something higher abaft than afore from the water.” This arrangement makes the deck’s fore end closer to the keel.[2]

Keltridge tells us that “height of the Gundeck beame from the lower edge of the Keele” is 21 feet 8 inches forward, and at 23 feet 4 inches aft, so the fore end of his deck is closer to the keel than the aft end. The drafts of his ship at the bow and stern are 19 feet, and 21 feet, respectively. Therefore, the fore end of Keltridge’s lower gun deck is four inches further from the water than its aft end.

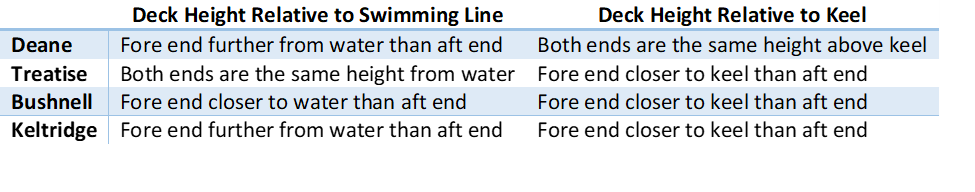

Table 5 summarizes the relationships between the fore and aft ends of the deck with the swimming line and the keel. The variability in the deck’s height relative to the swimming line is clear, as is the fact that Deane’s stated deck placement relative to the keel is unusual. He is the only source listed to place the fore and aft ends of his decks at the same height above the keel. All the other sources place the deck’s fore end closer to the keel. This leads us to once again question whether his Doctrine reflects his actual shipbuilding practices (we previously questioned this in the section on Data Sources).

Table 5. Fore and Aft Deck Heights Relative to the Swimming Line and Keel

The deck’s height on the current plans is derived from a document written in 1639 or 1640. It tells us the ports were 5 feet from the water amidships, 6 feet from it forward, and 6 ½ feet from it abaft. This yields a 2 ½ foot deck rise aft of the midship bend (it is 2 feet 10 inches if one interprets the latter as the height of the aftmost ports on the ship’s side) and a six inch rise fore of this bend.

[1] "Orlop" refers to the lowest of the two gun decks on the Treatise's ship.

[2] Bushnell does not tell us the deck’s height above the keel. However, he does tell us that the swimming line is 9 feet above the keel fore, and 10 feet above it aft, and that the fore and aft deck is 6 inches and 1 foot, respectively, above the water. Summing these two figures together tells us that the fore end of his deck is 9 feet 6 inches above the keel, and the aft end is 11 feet above it.

[3] Deane’s keel is 80 feet long aft of the midship bend. However, the deck’s aft end is aft of the keel because the post is at an angle. I therefore added his post rake of 5.50 feet to 90 feet to obtain a total length of 85.50 feet. His deck rises 16 inches, so it rises 0.19 inches per foot. Multiplying this by the sum of the aft two-thirds of the Sovereign’s keel plus its post rake gives a rise of 17.34 inches. I rounded this to 18 inches.

It is difficult to make the deck rise more than this because its allowable rise is constrained by the post’s height (i.e., the wing transom’s height, which is also the height of the chase port sills), the size of this deck’s stern chase ports, and the heights of these ports above the decks. As we progressively increase the deck’s rise aft of the midship bend, we must make the ports progressively smaller and/or closer to the deck to maintain the post’s height, and we quickly find that the ports become too small, or too close to the deck.

[4] The wales on the Pett painting also slightly dip here, which provides supporting evidence for the course of the deck I have used.

References

Ferriero, Larrie D. 2007. Ships and Science. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.Heywood, Thomas. 1637. A True Description of His Majesties Royall Ship, Built this Yeare 1637 at Wooll-witch in Kent. To the great glory of the English Nation and not paraleld in the whole Christian World. London: John Oakes.

Laughton, L. C. Carr. 1932. "The Royal Sovereign, 1685." The Mariner's Mirror 18 (2): 138-150.

Lavery, Brian. 1984. The Ship of the Line. Vols. Volume II: Design, Construction and FIttings. Londin: Conway Maritime Press.

Mainwaring, Henry. 1922. The Life and Works of Sir Henry Manwaring. Edited by G.E Manwaring and W.G. Perrin. Vol. 2. 2 vols. London: THe Navy Records Society.

Last edited:

Section IV: The Sheer Plan (continued)

The Length of the Sovereign’s Lower Gun Deck

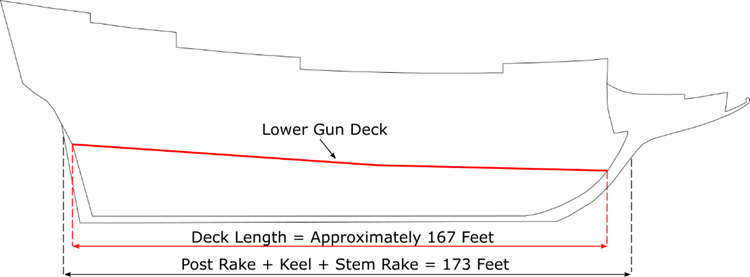

The length of the Sovereign’s lower gun deck at its launch is commonly given as 167 feet 9 inches. It was not. Gun deck lengths were not routinely recorded until 1677 (Lavery 1984, 9), so the length of the Sovereign’s lower gun deck in 1637 is unknown. (Fox, Personal Communication) We can only estimate it with the understanding that this estimate will be imperfect.One way to estimate the deck’s original length is given by a rule of thumb. It tells us that it should be 96.5% of the ship’s length from the rake of the post to the stem’s outer face (see Figure 27). (Fox, Personal Communication) Applying this percentage to the Sovereign yields 0.965 times 173 feet = 166.945 feet, which we can round to 167 feet. This percentage, however, was derived from ships with vertical stems and, as discussed in the section on the stem, the keels of these ships were extended at the bow when compared to ships whose stems were not vertical. This caused the lower gun decks of ships with vertical stems to be longer. Since the Sovereign’s stem was not vertical (see the section on the stem), it had a shorter keel and a shorter gun deck. Therefore, the Sovereign’s lower gun deck should be a little shorter than 167 feet. (Fox, Personal Communication) It is not clear exactly how much shorter it should be, though.

Figure 27. Estimating the Sovereign’s Maximum Possible Gun Deck Length

Note: Drawing adapted from a sketch by Frank Fox (Fox, Personal Communication) Drawing is not to scale, and is intended only the illustrate the concept under discussion.

Finding out exactly how much shorter turns out to be difficult. A precise estimate of the gun deck’s length depends on knowing the sizes of more than 20 other dimensions, and we can only estimate most of them. To avoid a lengthy description of why this is the case, we will view the deck’s length as the distance from the stem’s rabbet to the post’s rabbet. This way, we only need to think about where the rabbets are. We already found its position at the stern when we described the post’s dimensions. This told us where the post’s exposed surface meets the hull. I assumed a 4-inch wide rabbet here. We partly found the position of the stem’s rabbet from the rakes of the stem’s inner and outer faces. However, the rabbet is notched into the stem, and we do not know how far the rabbet’s inner edge is from the stem’s inner face. Because we cannot precisely determine the rabbet’s position, we cannot precisely determine the lower gun deck’s length. The result is that we can only offer a “best guess.”

A reasonable way to arrive at a “best guess” is to first determine the length of a gun deck that is just a little too short, then find the length of a deck that is just a little too long, and use the length in midway between them as the final estimate of the deck’s length. This is accomplished using the mathematical model that underpins the present reconstruction.

A deck that is “just a little too short” is obtained by placing the rabbet’s inner edge at the stem’s inner edge. The rabbet was never placed here because there is there is no support for the planking’s inner surface. It could easily be pushed towards the inside of the ship which, therefore, would leak. The deck of a ship with a rabbet placed here is 166 feet 7 ⅝ inches long.

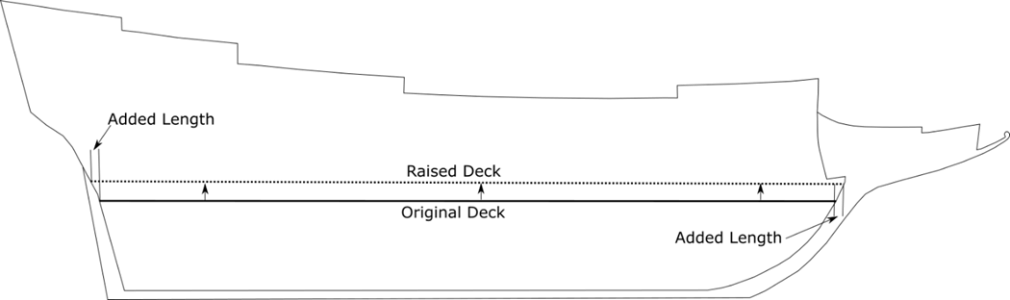

We can verify that this is “just a little too short” (as opposed to excessively too short) by considering how long this deck would be after it was raised during the 1659-1660 repair. Raising the deck lengthens it. The deck becomes longer because, as we move upwards, the post and the stem become further apart (see Figure 28). This creates more room between the rabbets and, hence, for the deck. Since the deck was 167 feet 9 inches long after this repair, we are looking for how much the “short” deck needs to be raised to reach this length. If our deck is appropriately short, the amount of rise should be close to the maximum amount the deck could have been raised during the repair. In the previous discussion of the van de Velde drawing, we noted that this was 18 inches. It turns out that our 166 feet 7 ⅝ inch deck needs to be raised about 20.37 inches to become 167 feet 9 inches long. Since the deck needs to be raised by an amount that is close to 18 inches, it is, appropriately, “just a little too short.”[1]

Figure 28. Association between Deck Height and Length

Note: This figure is provided only to illustrate the effect of raising the lower gun deck. It is not drawn to scale. The deck’s curvature is not depicted for simplicity’s sake.

We can use the same reasoning to find a deck that is “just a little too long.” We previously noted that the deck could have been raised by no less than a foot. Therefore, a deck that is just a little too long is a deck that needs to be raised by just a bit under a foot to become 167 feet 9 inches long. We obtain such a deck by moving the rabbet’s inner edge further away from the stem’s inner face until we reach this criterion. When we do this, we find that a rabbet 5 ½ inches from the stem gives an appropriate length. This deck is 167 feet 1 inche long, and needs to be raised 11.95 inches to become 167 feet 9 inches long.

Our final estimate of the lower gun deck’s length is the midpoint between the short and long decks we have just described. The stem’s rabbet is 2 ¾ inches from the stem’s inner face, and the corresponding deck is 166 feet 10 ⅜ inches long. Based on this length, we can estimate that the deck was raised somewhere around 16.16 inches during the 1659-1660 repair (Figure 29).

Figure 29. Simulating the 1659-1660 Repair

Note: The post’s angle and the stem’s radius were held at the values used in the current plans. This mimics the 1659-1660 repair, during which they were also unchanged. The rises fore and aft of the midship bend were also kept as they are on the present plans. The deck height increases shown on the X-axis are inches of increase above the final estimate of the deck’s height. The dotted red lines indicate 167 feet 9 inches on the ordinate and 16.16 inches on the abscissa.

The preceding is not meant to imply that raising the lower gun deck was the only change made to it during the 1659-1660 repair. Its camber may also have been altered. If it was, the result was not considered satisfactory later. A survey of the Sovereign performed in 1680 concludes that “The great defect we find in the ship is the cambring of her decks, the badness of her stem, and the timbers abaft in the breadroom.” [italics added] (cited in Laughton 1932). This complaint may have arisen because the Sovereign’s 1659-1660 camber was different from the 7-inch camber that was the style when the survey was conducted. This, however, is speculative.

[1] One could argue that we should seek a deck that needs to be raised by an amount that is closer to 18 inches, but this involved moving the rabbets inner surface aft of the stem, which is absurd.

References

Fox, Frank. "Personal Communication."— "Personal Communication."

Laughton, L. C. Carr. 1932. "The Royal Sovereign, 1685." The Mariner's Mirror 18 (2): 138-150.

Lavery, Brian. 1984. The Ship of the Line. Vols. Volume II: Design, Construction and FIttings. Londin: Conway Maritime Press.

Last edited:

Every time I read CharlieT's posts on this thread, I find myself screaming "More! MORE!!!"

Hardly. This level of in depth research, including comparisons to the research information of others, is usually unavailable to the average modeler when it's applicable to specific ship.Aha! So you're the one that's interested. I have the feeling that all of this documentation is putting everyone else to sleep, but I thank you very much.

Hi Charlie,

I am enjoying this discussion very much and learning a great deal.

Bill

I am enjoying this discussion very much and learning a great deal.

Bill