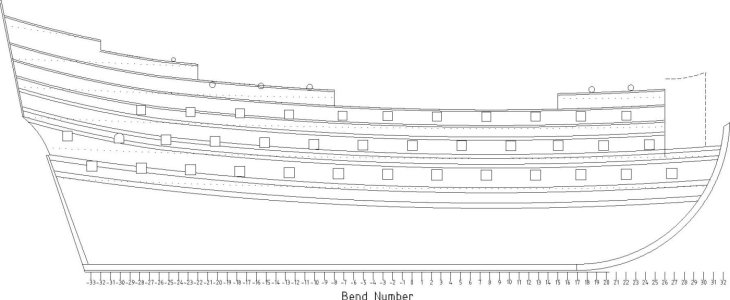

Section IV: The Sheer Plan (Continued)

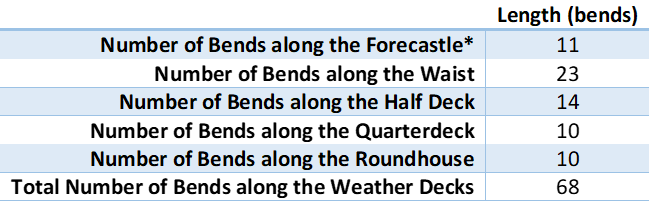

The Decks (continued)

The Forecastle

The Treatise tells us that the forecastle is “the uppermost part of the foreships directly over the chase and constrained between the bulkhead thereof and the stem.” As noted in the preceding subsection, the aft end of the Sovereign’s forecastle’s lies 15 bends fore of the midship bend. From here, it extends 11 bends forward to meet the beakhead bulkhead 26 bends fore of the midship bend. The forecastle’s foremost limit is defined by an arc that is, in turn, defined by the shape of the beakhead bulkhead. Fully discussing the beakhead bulkhead is a complex topic that will be discussed more fully in a later section. For now, suffice it to say that the Treatise tells us that the forecastle “must be cut off at the 3rd timber forward on, for the more conveniency of placing the bowsprit and fashioning the head.” The current plans mimic this by placing the foremost end of the curving beakhead bulkhead at bend 29, which is three bends less than the number of forward bends on the Sovereign.

According to the Treatise, the lengths of the forecastle’s deck is to be ⅔ of the stem’s inner rake. This would be about 25 feet 3 inches long on the Sovereign. The Sovereign’s forecastle is 27.5 feet long from its aft end to where the beakhead bulkhead begins, and 35 feet long from its aft end to its foremost point at the beakhead bulkhead.

The forecastle’s deck parallels the upper gun deck. Pett implies this when he tells us that “the third deck” was 7 feet 3 inches (plank-to-plank) above the upper gun deck.

The Half Deck

Kits for models of the Sovereign usually do not model the part of the half deck that cannot be seen from the ship’s outside, and previous attempts to reconstruct the Sovereign have not discussed this deck in detail. More attention to this deck is warranted because there are substantial differences between the way it is portrayed by the Pett painting and by the Payne engraving.

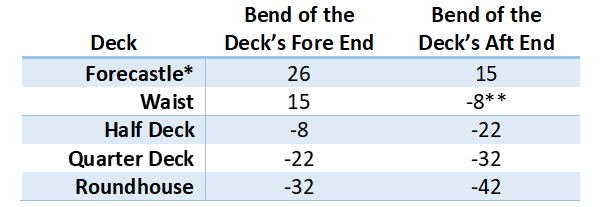

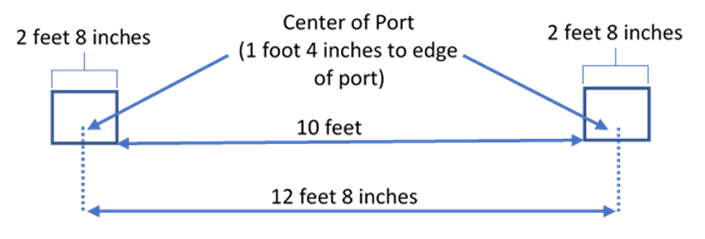

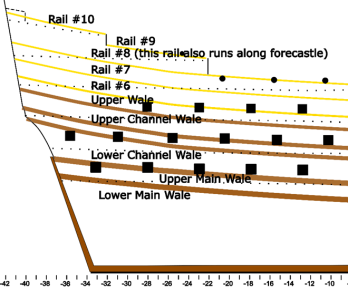

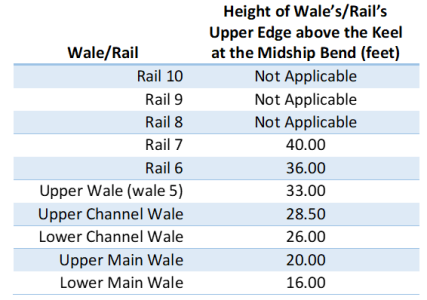

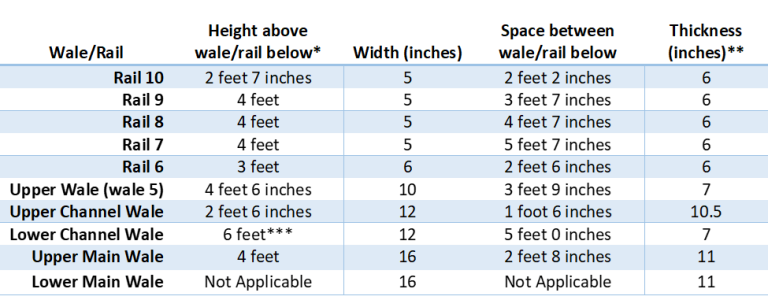

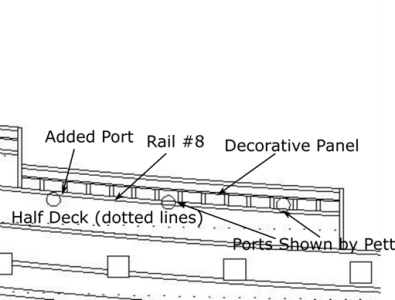

Let us first consider the way the half deck is portrayed in the Pett painting. The painting shows only two of the three ports that were actually along this deck because the aftmost port was added to the Sovereign after the painting was finished. Pett shows that the foremost port slightly cuts into a rail labelled as Rail #8 in Figure 30, and that the middle port is bisected by it. We can infer the aftmost port’s height by drawing a straight line that runs just under these two ports. This reveals that nearly all of the third port lies under Rail #8. Since the half deck must run somewhat below this line, the result tells us that the half deck is not following the run of the planking on the ship’s sides (i.e., the planksheer).

Figure 30. Pett’s Portrayal of the Half Deck’s Gun Ports

Note: Because I cannot show cropped, annotated versions of the Pett painting, I have instead provided a sketch. You can replicate the sketch on a downloaded version of the painting.

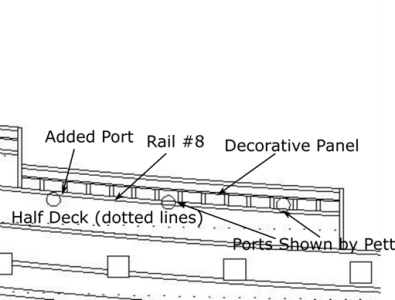

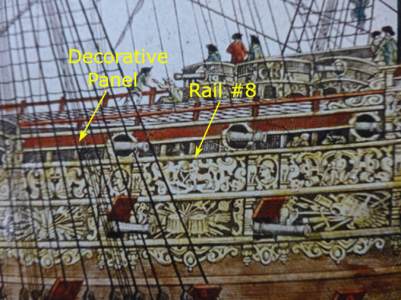

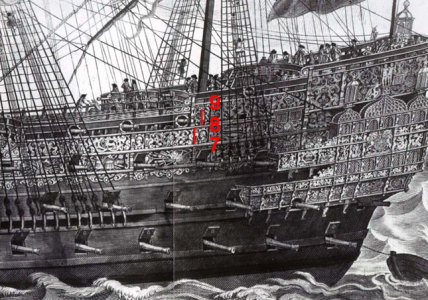

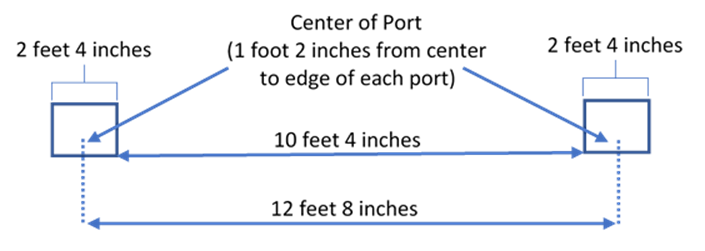

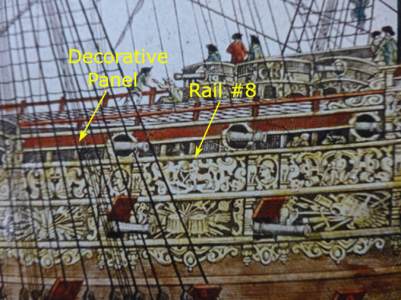

Payne’s engraving implies an entirely different half deck. One difference between it and the Pett painting is that the former shows the third port on the half deck (Figure 31). A more important difference is that the ports have been moved up, so they are now above Rail #8. This implies that Payne’s deck is higher than Pett’s. Also, because the ports run along the rail, the Payne engraving implies that the half deck follows the planksheer.

Figure 31. Payne’s Portrayal of the Half Deck’s Gun Ports

The differences between Pett’s painting and Payne’s engraving raise questions about where to place the half deck, and where to position its guns. It seems to me, at least, that it is sufficient to point out that the ship’s builder knew his own ship better than Payne knew it, and end the discussion here. However, because the differences between Pett and Payne lead to such substantially different reconstructions, and because Payne’s portrayal seems to have been used in every previous model of the Sovereign (or, at least, every model of it that I have seen), further examination of the Payne engraving is warranted.

One difference between Payne’s and Pett portrayals is that is that Payne’s gun ports are larger. Payne’s ports reach from rail #8 to nearly the top of the red, decorative panel that runs along the half deck. Pett’s foremost half deck port, shows that his ports reach only from rail #8 to the bottom of the decorative panel. All of Payne’s ports along the upper decks are large, and this hints at a possible problem with his portrayal of all of them.

A more substantial difficulty with Payne’s portrayal appears when we compare the number of half deck bends he shows to those shown by Pett. Pett portrays his deck as 14 bends long. Payne, on the other hand shows it as no more than 13 bends long. In characterizing his deck as “no more” than 13 bends long, I am assuming that there is a bend that lies just aft of the aftmost port on his deck, but just before the break at the quarterdeck. This bend is not visible on the engraving and, if Payne actually did mean to imply that a bend was here, it is obscured due to artistic perspective. The result is that this putative bend is so close to the bulkhead at the quarter deck’s fore end that one can plausibly argue that the engraving only shows 12 bends. Regardless, either Payne’s deck is at least 2 ½ feet shorter than Pett’s, or Payne has failed to draw one or two bends. The latter is most likely because the ports on the three gun decks will not correctly align with the breaks in the upper decks if the half deck has fewer bends than Pett shows. Regardless, Payne’s portrayal of the half deck is not done as carefully as we would like.

A third difficulty with Payne’s portrayal of the half deck is that this deck’s aftmost guns are precariously close to the bulkhead at the quarter deck’s fore end. If we take Payne’s portrayal literally, as many modelers have done, the aft side of his port is less than half the gun port’s width from it so, it is only about seven or eight inches from the bulkhead. Putting a port this close to a bulkhead means that it is difficult to aim the gun straight. This puts the bulkhead in jeopardy when the gun is fired and recoils. Although Pett does not show this port, equal spacing of his half deck ports places the aft side of the aftmost port a little over 2 ½ feet from the bulkhead at the quarterdeck’s fore end. This is a more reasonable distance from the bulkhead, and it again suggests that something is wrong with Payne’s portrayal.

Another difference between Payne and Pett is that the former puts the half deck’s foremost gun port just aft of the half deck’s third bend. It is just aft of the second bend in Pett’s portrayal. The result is that Payne’s placement puts the foremost port only three bends fore of the middle port, whereas Pett’s port is four bends away from it. Payne’s portrayal thus concentrates the guns’ weight more than Pett’s does. Pett’sFigure 30 portrayal is more satisfying because shipwrights sought to distribute the weight of the guns. This put less strain on the deck beams.

Yet a fifth difference between Payne and Pett is that the latter shows the middle gun port (which is the aftmost gun port on the Pett painting) as bisected by rail 8, whereas Payne shows the port as lying above the rail. Since the port must stay at a constant distance above the deck, Pett’s drawing is forcing the half deck down, whereas Payne’s engraving is pulling it up. Payne’s placement of this port assures us that his half deck follows the planksheer, and Pett’s portrayal tells us that it does not.

That Payne’s engraving suggests the half deck follows the planksheer is significant. This is contrary to common contemporary building practice. For example, the book “Great Ships” (Fox 1980) presents depictions of about 40 17th century ships. Two of the portrayals are ambiguous, but every one of the remaining ships with guns along its upper decks shows that these ports cut into the ship’s sides and, therefore, that the upper decks that do not follow the planksheer. Deane’s drawings also show that the upper decks do not follow the planksheer. It was thus uncommon for any of the aft upper decks to follow the planksheer.

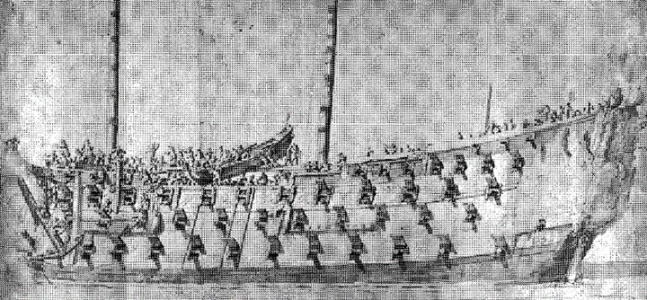

It is clear that that upper decks of the repaired versions of the Sovereign did not follow the planksheer. One example of this is van de Velde’s sketch of its starboard side previously shown in the section that discusses his drawing. Another example is his drawing of the Sovereign’s port side, which is shown in Figure 32. It is also shown in a third drawing by van de Velde, (Figure 33) which Henrik Bussman says is the Sovereign in about 1663 (Busmann 2002, 52), and a fourth one that is from about 1685 (Figure 34).

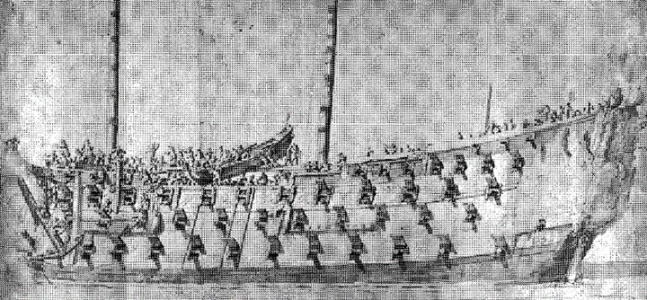

Figure 32. Van De Velde’s 1673 Sketch of the Sovereign (Port Side)

Note: The half deck’s length had been modified by the time of this sketch.

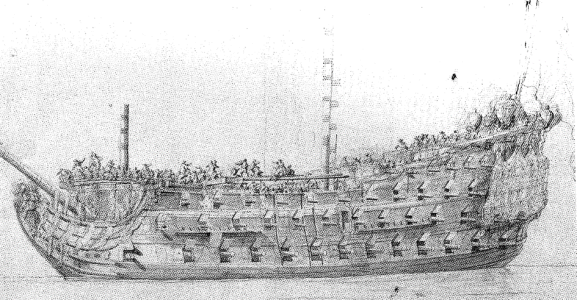

Figure 33 Van de Velde’s Drawing of the Sovereign from 1663(?)

Note: In This is an unusual drawing, so I have provided extended comments about it. If the drawing is, indeed, from any date after 1660, it should not show the aftmost port that was initially on the middle gun deck. This port was removed during the 1659-1660 repair. Van de Velde not only shows it, he places in rather high. He puts most, if not all, of this port as lying above the lower edge of the lower channel wale. This is unlike his most famous portrayal of the

Sovereign, unlike Payne’s engraving, and unlike the Pett painting, all of which show most of the port below the lower channel wale. The two ports fore of this one also appear higher than in other portrayals. The relatively high placement of these ports suggests the deck had been raised by the time of this drawing, which is consistent with the changes made during the 1659-1660 repair.

Van de Velde also portrays the port next to the middle gun deck’s aftmost port as lying under the quarter galleries instead of being where the now-removed quarter gallery extensions were. This is incorrect. He shows this and the aftmost port as arched, and the latter port as cutting into the lower quarter gallery. No other depiction of this port shows these latter two features.

I have no convincing explanation for this drawing. That van de Velde shows the aftmost port raises the possibility that he was not attempting to show the

Sovereign as it actually was. He may have been attempting to see how the now-removed port would fit on the ship that was before him. This, however, does not explain why he shows the port next to the aftmost port as being under the quarter gallery. On the other hand, the drawing appears unfinished. The outlines of several ports along the fore half of the lower gun deck are present, and this gives the impression that van de Velde was still working on where to place them, or that he had placed them to his satisfaction, but had not yet erased where he originally drew them. If nothing else, the drawing highlights the difficulties of using 17th century artwork to make definitive statements about the

Sovereign, even if that artwork is by an accomplished maritime artist.

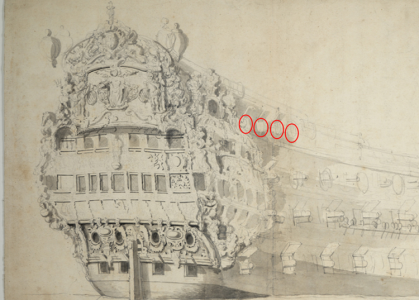

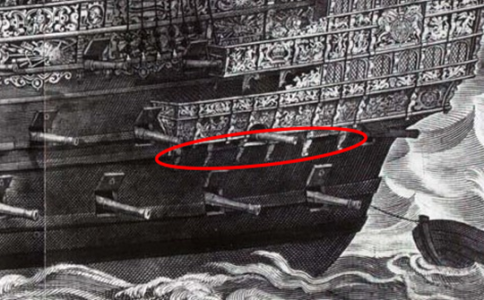

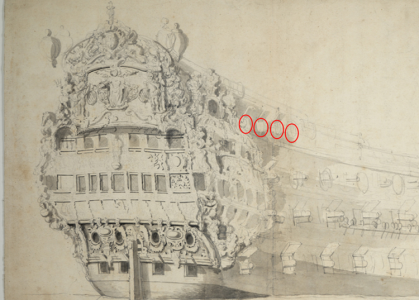

Figure 34. Van de Velde’s 1685 Drawing of the Sovereign

Note: The ports along the upper decks are difficult to see in this drawing, so I have circled them in red.

These drawing are important because they make it difficult to argue that the Pett painting shows the Sovereign’s half deck was planned one way, but that Payne shows it was built another way. If this were the case, the four drawings shown above would show yet a third change in the half deck’s placement. This is an unusually mobile half deck for a ship that began with flush decks. Another way of thinking about such a deck is that decks probably did not commonly run with the planksheer because shipwrights of the Sovereign’s time found this arrangement more satisfactory than decks that did run with it. If this is the case, then the Sovereign was originally designed in a manner that shipwrights would have found satisfactory to one they later considered less satisfactory, so it was changed back to a “satisfactory” deck. This seems to me to be a difficult position to hold.

Payne’s portrayal of the half deck as following the planksheer has downstream consequences. If the deck is allowed to continue along this trajectory to the stern, it is impossible to correctly align the upper and lower windows on the stern because the half deck is more than eight feet too high. This trajectory also makes it impossible to correctly position the upper quarter gallery. This is because there was a door on the half deck’s aft end that led to this gallery (just as there is a door upper gun deck’s aft end that led to the lower quarter gallery; the galleries will be discussed in a later section), and we need to raise the upper quarter gallery’s aft end by more than eight feet to meet this door. Since the lower quarter gallery also meets its own door, the result is that upper and lower quarter galleries that are not parallel to each other[1], which is contrary to all contemporary depictions of the Sovereign.

The only way to line up the stern windows, and make the two quarter galleries parallels is to put a fall in the deck to bring its aft end down to an appropriate level (this is seen on plans by John McKay, who has put two small “falls” in his half deck). This seems contrary to Pett’s intentions. He tells us that “the third deck” is 7 feet 3 inches above the upper gun deck. If the “third deck” referred only to the forecastle, Pett could have easily said so. He did not. If, on the other hand, we take the term “third deck” to refer to not only the forecastle, but also the half deck, there is no need to put a fall in the deck. When the entire half deck is 7 feet 3 inches above the upper gun deck, the stern gallery windows align with each other, the quarter galleries are parallel, and both align with everything else just as they should.

Making the entire half deck is 7 feet 3 inches above the quarterdeck makes it parallel to the upper gun deck. On the face of it, this appears unusual. It is thought that it was customary to elevate the half deck’s aft end to create more headroom in the cabins below. One can question, though, whether this was customary in the early 17th century, or whether anything on what was only England’s second three-decked ship can be said to be customary. More importantly, though, is that the lack of increased headroom is not solely dictated by the height of the half deck’s aft end. It is also dictated by the need to correctly align the upper and lower stern gallery windows with each other, and to make the two quarter galleries parallel to each other. If we attempt to create the “customary” increase it headroom, we must misalign these parts of the Sovereign. Accordingly, the “customary” aft increase in headroom could not have been present on this ship.

The discrepancies between Pett’s painting and Payne’s engraving leave us with four alternatives:

- The first is that original design of the Sovereign’s half deck, as portrayed in the Pett painting, was changed just before the ship was built, so that it now looked like the Payne engraving. However, Pett would have no reason to do this, particularly since the change yielded a ship not built according to common practice. Furthermore, no records have been located to suggest that a change was made.

- Second, we can hold that the Sovereign’s half deck was changed in response to the King’s addition of guns to the Sovereign. The difficulty here is that there is no good reason to rip out an existing deck and replace it with a different one when the original deck could also carry the added guns. Also, no records have been located to support this assertion.

- The third alternative is that the Pett painting is correct, so Payne’s engraving is not.

- The fourth alternative is the converse of the third, that Payne is correct and Pett is not. Choosing this latter alternative requires us to make several assumptions that are worth delineating.

In delineating these assumptions, bear in mind that when we decide not use the Pett painting, we are making all of them. Failure to believe any one of them calls Payne’s portrayal into question The assumptions we must make are:

- The ship’s builder has inaccurately located the half deck’s foremost port.

- The ship’s builder put the aftmost port on his painting (which later becomes the middle gun port) at the wrong height.

- The height that Phineas Pett gives for the half deck above the upper gun deck is either wrong, or does not apply to the half deck. In making this assumption we must also ignore the fact that Phineas Pett’s given half deck height places the two ports shown on the Pett painting and the third port implied by this painting just as the painting shows.

- The Sovereign’s half deck did not follow common building practices.

Making these assumptions means that we are assuming that part of what the ship’s designer tells us about his ship is irrelevant or wrong, and what the builder shows us about his half deck is also wrong. It is difficult to dismiss both the information provided by the ship’s designer and its builder. Doing so requires proof that extends beyond existing artistic portrayals of the Sovereign. Stated in another way, a decision to place the half deck as shown by Peter Pett is based both on artwork (Peter’s painting) and historical records (Phineas’ list of dimensions). A decision to position the half deck as Payne portrays is based only on contemporary artwork which, as discussed in the section “Which Artwork Should We Use?”, is not always reliable. A decision to use the Payne engraving needs to also be supported by historical records to be on an even footing with the Petts’ placement of the deck.

Based on all of the preceding considerations, the conclusion here is that the half deck’s gun ports on the Sovereign were positioned as shown in Figure 30, and that the half deck did not run with the planksheer. To put it plainly, the Payne engraving is incorrect. The correct half deck follows the pattern of the middle and upper gun decks; it is not raised to create headroom aft, even though it often was in later ships. The Sovereign’s design was thus, simpler than that of later ships, which is a theme I will return to.

A number of reasons for Payne’s error can be suggested, but none can be proven. For example, Payne was obviously aware that the King had added guns to the Sovereign (after all, he portrays the added guns), but the aftmost one may not have been installed at the time of his engraving. As a result, Payne guessed where it would go and aligned the other ports with it. Not being a maritime artist, he guessed wrong. Alternatively, Payne probably engraved his plates from a sketch he made at dockside. His sketch may have been wrong or unclear.

References

Busmann, Hendrik. 2002.

Sovereign of the Seas. Hamburg, Germany: Deutches Schiffahrtsmuseum, Bremerhaven, und Convent Verlag, Hamburg.

Fox, Frank. 1980.

Great Ships. London: Conway Maritime Press.

[1] We implicitly set the position of the lower quarter gallery when we positioned the middle and upper gun decks.