Now for some housekeeping and two small topics.......

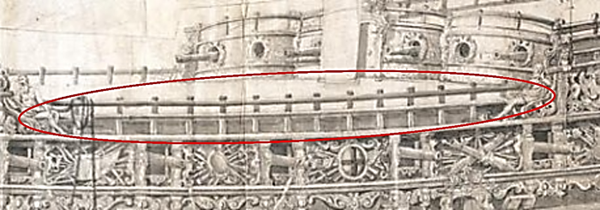

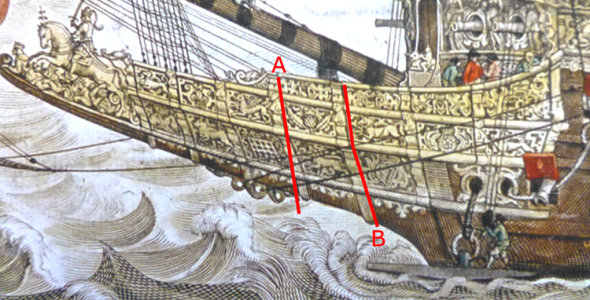

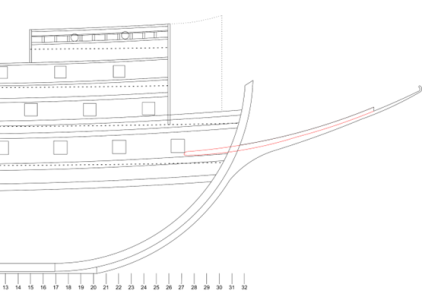

Figure 46 Decorative Panels along the Forecastle

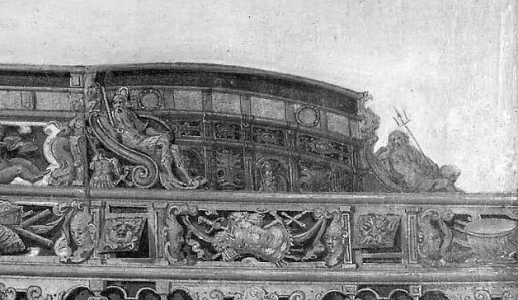

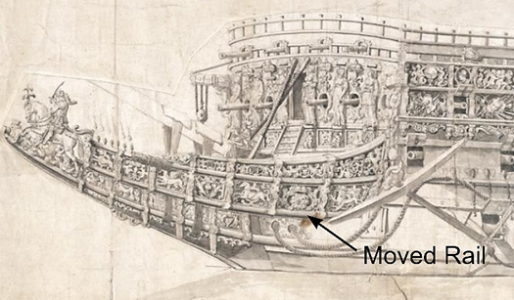

Payne and van de Velde also show railings above the decorative panels along the forecastle and half deck, and an analogous set of rails along the waist. Van de Velde’s portrayal of them along the waist is shown in Figure 47. Pett shows no railings here, but he may have considered them ancillary (which is why he does not show masts). These rails, and their dimensions, are shown in the attached schematics.

These uppermost rails are associated with the decks that have gratings over them. It would be reasonable for modelers who do not cover their decks with gratings to omit these rails, and portray only the decorative panels.

Figure 47. Van de Velde’s Portrayal of the Rails along the Waist

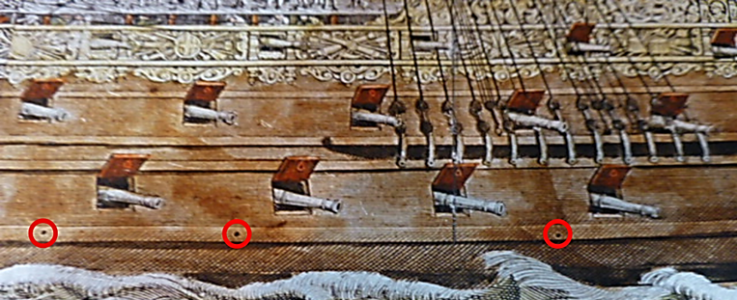

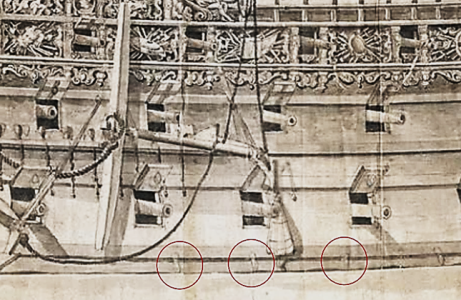

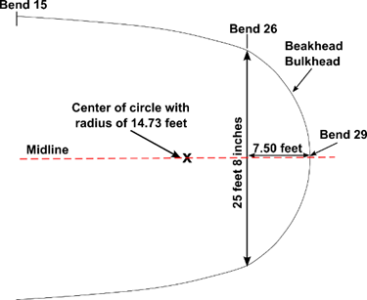

The Payne engraving shows what appear to be 7 scuppers on the Sovereign (three of them, circled in red, are shown in Figure 48) Van de Velde’s copy of the Payne engraving clearly shows them as scuppers because he shows them with their sleeves.(Figure 49) The van de Velde drawing shows them closer to the wale’s bottom than the Payne engraving. All the scuppers shown by Payne and van de Velde drain the lower gun deck.

Figure 48. Scuppers in the Payne Engraving

Figure 49. Scuppers in the van de Velde Drawing

The foremost and aftmost scuppers on Payne and van de Velde lie below the upper mail wale. The remaining scuppers in the Payne engraving all puncture it. Shipwrights were reluctant to puncture the wales, (Fox) so portraying them as doing so may be another error in the engraving. A more appropriate place for scuppers is below the upper main wale.

Only van de Velde shows an entry door in the Sovereign’s hull. It is on the ship’s port side. It is not seen on the Pett painting because he shows the ship’s starboard side. Payne, who does show the port side, does not portray this door. There are only two explanations for this; either Payne made a mistake, or the door was added after the Sovereign was launched.

It is unlikely the door was added after the Sovereign’s launch. This ship was designed as an attraction. A door provides an easy way for visitors to enter the ship. The alternative is to have them board by climbing up nettings, and going over the gunwale at the waist. This required considerable exertion, especially on a 3-decker. In a later century, one sea captain who felt that his lieutenants were overweight, ordered the entry door sealed to make them climb aboard. (L. Laughton 1922, pg 188) It is unlikely that visitors, including visitors like Samuel Pepys and his lady friends, noblemen, and noblewomen wearing dresses (who would incur the immodesty that climbing an netting would entail), would be subjected to a such climb. It is more likely that Payne made a mistake.

Others seem to have regarded the Payne engraving as a near-perfect representation of the Sovereign, and have not acknowledged the possibility that this is an error. This, for example, seems to be why Sephton tells us, without evidence or explanation of how it could have been accomplished, that “we are left with the suggestion that, as the engraving is in reverse the entry port may have been on the port elevation only [italics added].” (Sephton 2011, 46) It is more likely that an omission as obvious as a missing door indicates that the engraving was prepared with less than perfect attention to detail.

I have placed the door as shown by van de Velde, just fore of the middle gun deck’s seventh port, and so that the beams for the deck above remain intact. Van de Velde shows that its width is about that of a port on the lower gun deck, 30 inches. This door, like the entry doors to lower quarter gallery, is 7 feet high. The door associated with the upper quarter gallery is 6 feet 6 inches high.

Payne shows several windows on the ship. Knyff also shows them. Pett does not, but he may have considered them ancillary. It seems more likely than not that the Sovereign had windows to give light to some of the darker regions of the ship’s interior. The only other way to provide light in the 17th century was to burn something, and captains and crews sought to avoid this wherever possible. They were rightfully afraid of fires on board. I have placed 24 x 20 inch double windows at the quarter deck’s aft end (these serve the upper gun deck and the half deck), and a 20 x 20 inch window (that serves the quarter deck) under the roundhouse.

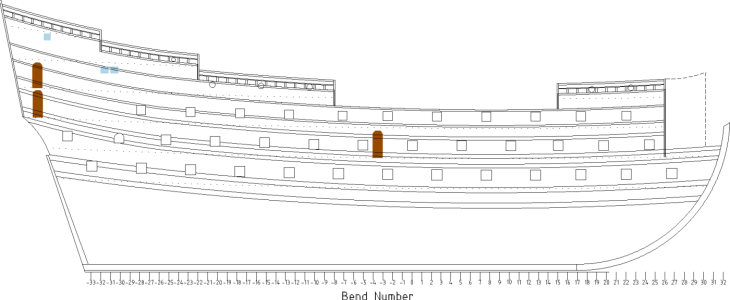

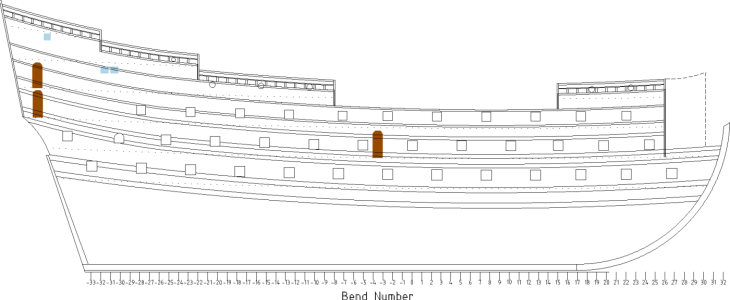

The figure below shows the reconstruction up to this point. Doors that lead to the quarter galleries are also shown. This figure does not show the upper railings along the grated weather decks.

Laughton, L.G. Carr. 2006. Old Ship Figure-Heads & Sterns. Ontario, Canada: Algrove Publishing Limited.

Laughton, L.G.H. 1922. Old Ship Figure-Heads and Sterns with which are Associated galleries, Hancing-Pieces, Catheads and Divers Other Matters that Concern the 'Grace and Countenance' of Old Sailing Ships. London: Halton & Truscott Smith.

Sephton, James. 2011. The Sovereign of the Seas. Stroud: Amberly Publishing.

The Sheer Plan (continued)

The Decorative Panels and Rails Above the Bends

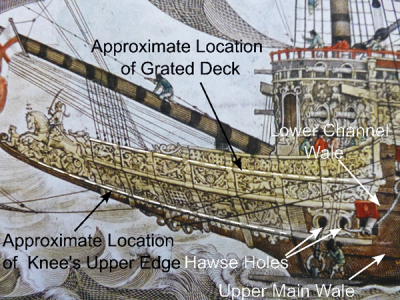

Pett and Payne, and van de Velde all show decorative panels along the bends’ tops. These panels and rails appear everywhere except along the waist. Payne shows them as red (Figure 46). There is a small rail below this panel and another one above it. Payne portrays these two rails as of the same width. Pett shows the upper rail as wider. I have followed Pett. Schematic diagrams providing their dimensions are attached.Figure 46 Decorative Panels along the Forecastle

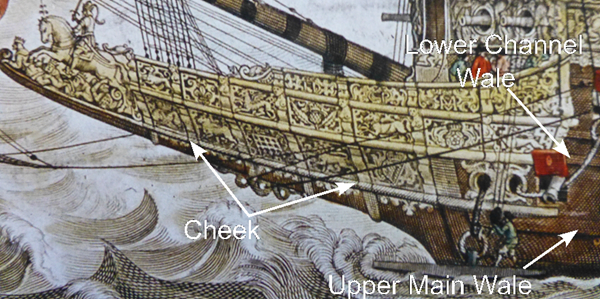

Payne and van de Velde also show railings above the decorative panels along the forecastle and half deck, and an analogous set of rails along the waist. Van de Velde’s portrayal of them along the waist is shown in Figure 47. Pett shows no railings here, but he may have considered them ancillary (which is why he does not show masts). These rails, and their dimensions, are shown in the attached schematics.

These uppermost rails are associated with the decks that have gratings over them. It would be reasonable for modelers who do not cover their decks with gratings to omit these rails, and portray only the decorative panels.

Figure 47. Van de Velde’s Portrayal of the Rails along the Waist

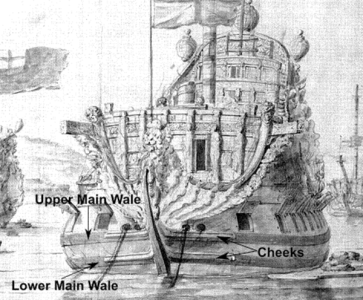

Scuppers

Scuppers are holes in a ships’ side for draining water. Lead tubes that angled downwards and into them from the side of the deck. Scuppers were fitted with leather sleeves.The Payne engraving shows what appear to be 7 scuppers on the Sovereign (three of them, circled in red, are shown in Figure 48) Van de Velde’s copy of the Payne engraving clearly shows them as scuppers because he shows them with their sleeves.(Figure 49) The van de Velde drawing shows them closer to the wale’s bottom than the Payne engraving. All the scuppers shown by Payne and van de Velde drain the lower gun deck.

Figure 48. Scuppers in the Payne Engraving

Figure 49. Scuppers in the van de Velde Drawing

The foremost and aftmost scuppers on Payne and van de Velde lie below the upper mail wale. The remaining scuppers in the Payne engraving all puncture it. Shipwrights were reluctant to puncture the wales, (Fox) so portraying them as doing so may be another error in the engraving. A more appropriate place for scuppers is below the upper main wale.

Doors and Windows

Entry doors were likely present on all 3-decked ships. They are first portrayed on Pett’s Prince Royal. (L. Laughton 2006, 188)Only van de Velde shows an entry door in the Sovereign’s hull. It is on the ship’s port side. It is not seen on the Pett painting because he shows the ship’s starboard side. Payne, who does show the port side, does not portray this door. There are only two explanations for this; either Payne made a mistake, or the door was added after the Sovereign was launched.

It is unlikely the door was added after the Sovereign’s launch. This ship was designed as an attraction. A door provides an easy way for visitors to enter the ship. The alternative is to have them board by climbing up nettings, and going over the gunwale at the waist. This required considerable exertion, especially on a 3-decker. In a later century, one sea captain who felt that his lieutenants were overweight, ordered the entry door sealed to make them climb aboard. (L. Laughton 1922, pg 188) It is unlikely that visitors, including visitors like Samuel Pepys and his lady friends, noblemen, and noblewomen wearing dresses (who would incur the immodesty that climbing an netting would entail), would be subjected to a such climb. It is more likely that Payne made a mistake.

Others seem to have regarded the Payne engraving as a near-perfect representation of the Sovereign, and have not acknowledged the possibility that this is an error. This, for example, seems to be why Sephton tells us, without evidence or explanation of how it could have been accomplished, that “we are left with the suggestion that, as the engraving is in reverse the entry port may have been on the port elevation only [italics added].” (Sephton 2011, 46) It is more likely that an omission as obvious as a missing door indicates that the engraving was prepared with less than perfect attention to detail.

I have placed the door as shown by van de Velde, just fore of the middle gun deck’s seventh port, and so that the beams for the deck above remain intact. Van de Velde shows that its width is about that of a port on the lower gun deck, 30 inches. This door, like the entry doors to lower quarter gallery, is 7 feet high. The door associated with the upper quarter gallery is 6 feet 6 inches high.

Payne shows several windows on the ship. Knyff also shows them. Pett does not, but he may have considered them ancillary. It seems more likely than not that the Sovereign had windows to give light to some of the darker regions of the ship’s interior. The only other way to provide light in the 17th century was to burn something, and captains and crews sought to avoid this wherever possible. They were rightfully afraid of fires on board. I have placed 24 x 20 inch double windows at the quarter deck’s aft end (these serve the upper gun deck and the half deck), and a 20 x 20 inch window (that serves the quarter deck) under the roundhouse.

The figure below shows the reconstruction up to this point. Doors that lead to the quarter galleries are also shown. This figure does not show the upper railings along the grated weather decks.

References

Fox, Frank. Personal Communication.Laughton, L.G. Carr. 2006. Old Ship Figure-Heads & Sterns. Ontario, Canada: Algrove Publishing Limited.

Laughton, L.G.H. 1922. Old Ship Figure-Heads and Sterns with which are Associated galleries, Hancing-Pieces, Catheads and Divers Other Matters that Concern the 'Grace and Countenance' of Old Sailing Ships. London: Halton & Truscott Smith.

Sephton, James. 2011. The Sovereign of the Seas. Stroud: Amberly Publishing.

Attachments

Last edited: