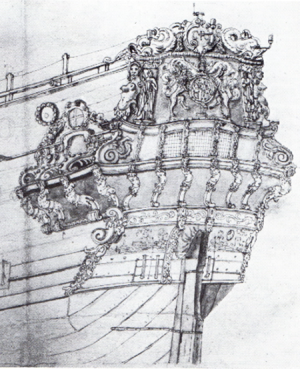

Section V: The Stern

General Appearance

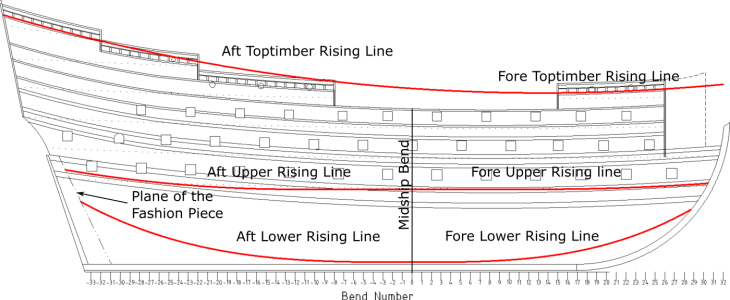

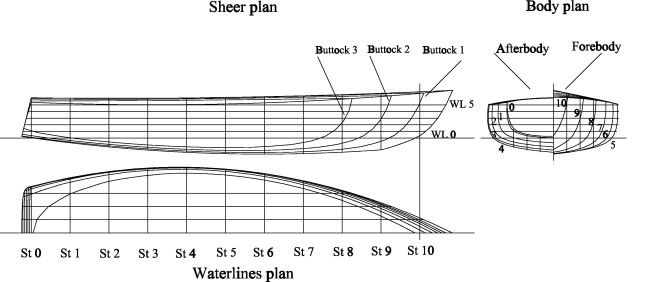

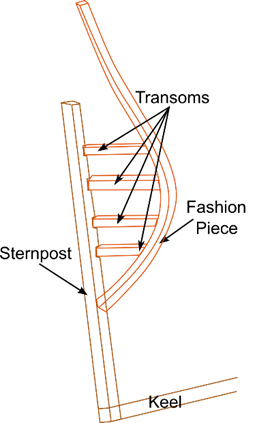

The shape of the Sovereign’s stern has been the subject of controversy. The issue is whether it had a round tuck or square tuck stern. For this discussion, we can think of the tuck as that part of the stern that lies below the counter[1]. When this part of the stern is flat, the stern is called a square tuck stern. When the planking along it is curved, the stern is said to have a round tuck. Whether the tuck is square or round depends on the position of the fashion piece.

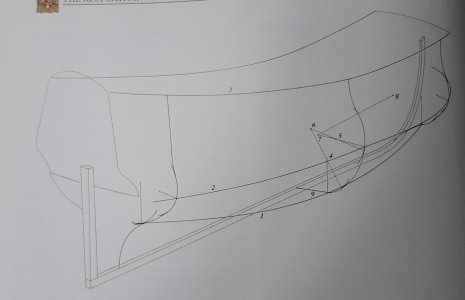

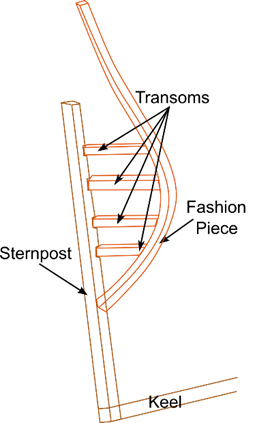

The fashion piece on a ship with a square tuck stern runs along the angle of the sternpost (the sketch in Figure 65 depicts this). On a round tuck stern, the fashion piece is moved forward, and away from the post (Figure 16 in the section on the sternpost shows the position of a 17th century fashion piece on a ship with a round tuck stern). It also runs at an angle, so it is relatively close to the post at its top, and further far from the post at its bottom. This movement of the fashion piece away from the post causes the planking between the fashion piece and the post to curve.

Round tuck sterns were refined during the first half of the 17th century. Initially, separate planks were used along the tuck, so no steam-bending was necessary. Later, the planking along the ship’s side was steamed, so it could be bent over the fashion piece and continue along the tuck on its way to the post.

Figure 65. The Fashion Piece on a Square Tuck Stern

Round tuck sterns were more expensive to build, but: (a) provided greater strength; (b) provided better water flow the to the rudder which facilitated better steering; (c) were more aesthetically pleasing, and; (d) were less liable to leak than square tuck sterns. (Goodwin 1998, pgs 60-61)

Figure 66. Round and Square Tuck Sterns

The square tuck stern is that of the

Vasa (photo by Jonathan Cardy – Own work, November, 2015,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45380642). The early round tuck stern is that of the

Batavia (photo by Don Hitchcock, October, 2015,

https://www.donsmaps.com/batavia.html, Source: The Shipwreck Galleries, Western Australia Museum, Fremantle, Western Australia). The round tuck stern is of the

Amsterdam (photo by McKarri, Self-Photographed, July, 2009,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Amsterdam-Heck.JPG.)

There is strong evidence that the Sovereign had a round tuck stern. Such a stern is suggested by the shading at the stern of the Pett painting (Pett has also shaded the area around the bow, so his shading is meant to represent curvature). A painting by Knyff (Figure 71) and a 1673 drawing of the Sovereign by van de Velde (Figure 32) also show that the Sovereign had a round tuck stern. These three portrayals are all consistent with the idea that no large English ship was built with a square tuck stern after the early 1620’s. (Fox, Personal Communication)

Saying the Sovereign had a round tuck stern leads us to ask whether it was more like the later round tuck stern, or more like the earlier one. Although no definitive answer is possible, it is plausible that the stern was more like the latter. This is suggested the stern shown in a drawing by a van de Velde the Elder, and from about 1634, of what appears to be and English third rate ship with such a stern (Howard 1979, 103) This drawing is shown in Figure 67. It could be what is portrayed in a drawing attributed to Lely (Figure 68 and Figure 70). (P 2020)

Figure 67 An Early, English Round Tuck Stern

There are several noteworthy oddities in this painting. Of interest here is that only the starboard side of the Lely painting shows a square tuck. The port side shows a round tuck. (Anderson 1913) However, the portrayal of the Sovereign’s starboard side is problematic. It was restored, and the restoration is not accurate. The misshapen starboard, upper, centermost gallery window is evidence of this.

We find another oddity when we try to determine which the decks the painting’s guns are on. As R.C. Anderson has pointed out, (Anderson 1913) although the lowest row of starboard gun ports appears to be on the lower gun deck, this may not be their true location. If it were, the uppermost guns would have to be those on the half deck, and these would probably not be visible from the stern. Anderson also notes that the “lower dead-eyes of the main shrouds can be seen just level with the middle tier of guns shown, and this proves almost conclusively that those must be the middle-deck guns.” The guns below them are thus those of the lower gun deck, and the painting’s lowest row of ports are ports that did not exist on the Sovereign (see Figure 68). Anderson continues by saying “This being so, we have to seek an explanation of this row of port-lids, and this can probably be found in the work of the restorer. There is no need to look far for evidence of his activities; they are shown clearly enough by the fact that the ship appears to have a round tuck on the port side and a square tuck on the starboard. One side must have been ‘touched up’ and to judge from the general run of the planks it is the starboard side that has suffered most. It is, too, on this side that the supposed port-lids appear; surely the man who could make half of a round stern square would be able to transform a dimly seen wale into a row of projecting port-lids.” (Anderson 1913) These conclusions have been echoed by others, who note that the square tuck stern and the row of “impossible” gun ports below the lower deck may be the work of “an ill-advised restorer.” (Fox, Great Ships 1980, 44)

Figure 68. R.C. Anderson’s Criticism of the Lely Painting

Note: Painting from the National Maritime Museum

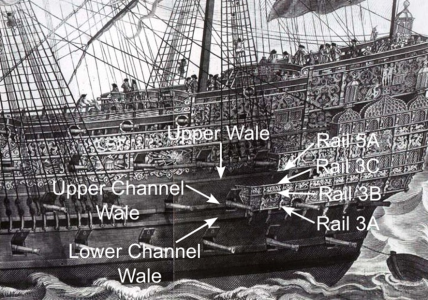

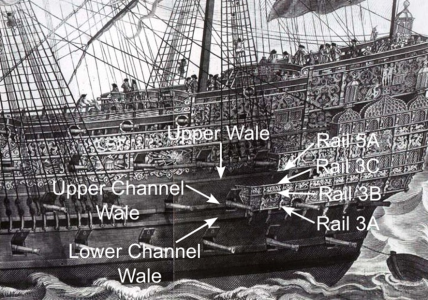

There is another potential problem with the Lely painting, and this one pertains to both sides of the ship, not just the starboard side. Explaining this problem requires that we first consider the relationship between the gallery rails that run along the ship’s side, and the rails along the stern. This requires some nomenclature. I will use the Payne engraving for this. It shows that the Sovereign’s lower quarter gallery sits within a space defined by the lower channel wale near its bottom, and by the upper wale near its top. In between these two wales are three rails, which I have labelled wales 3A, 3B, and 3C. Just above the upper wale is another railing, rail 5A (Figure 69). This latter rail runs just above the windows along the lower quarter gallery. Rails 3A and 3B are particularly important to the present discussion.

Figure 69. Naming the Lower Quarter Gallery Rails

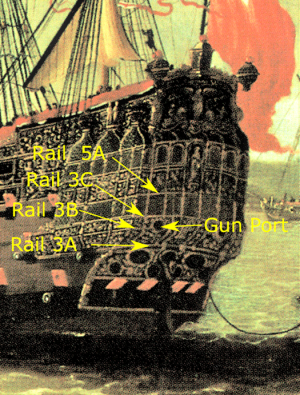

The quarter gallery windows and rails wrap around the stern and stay at the same heights, so it is not surprising that the Lely painting shows the corresponding rails (Figure 70). Notice that the upper gun deck’s chase ports are shown as lying below rail 3B, and that a decoration surrounding these ports fills in the space between this rail and the port. Also, notice that the upper gun deck’s stern chase ports are very close to rail 3A.

Figure 70. Stern Rails on the Lely Painting

Note: Painting from the National Maritime Museum

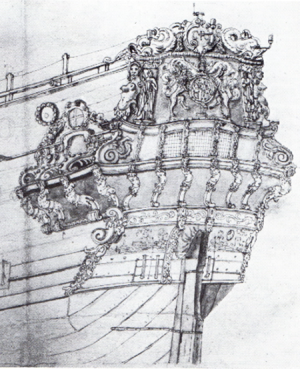

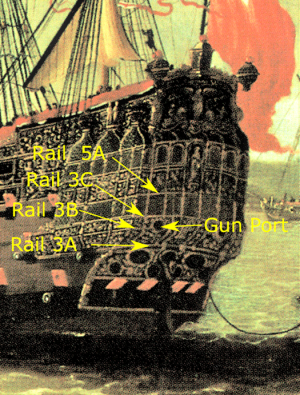

A painting by Jacob Knyff shows something different. The painting is anachronistic because it purportedly shows the Sovereign in 1673, but “It may be that Knyff used an earlier picture as his guide, perhaps one dating from the 1650’s.” (Fox, Great Ships 1980, 44) The portion of the painting relevant to the present discussion is shown in Figure 71. Although the Knyff painting (Figure 71) shows the same stern wales and rails as the Lely painting, Knyff shows rail 3B as cut by the upper gun deck’s stern chase ports, and the decoration that surrounds them is now between the port and rail 3C. Also, the height of the upper gun deck’s stern chase ports above rail 3A is now about equal to the diameter of these ports. Frank Fox maintains that, in some ways, this is a more accurate representation of the Sovereign’s stern. (Fox, Personal Communication)

Figure 71. Stern Rails on the Knyff Painting

Note: The painting shows that the long extensions of the quarter galleries have been removed. Also notice that there are windows at the quarter galleries’ aft ends. The Lely painting does not show these windows. It cannot be conclusively determined whether the difference is a result of an error in one of the paintings, or the result of a modification that Knyff correctly portrays. It is, however, preferable to portray the

Sovereign with these windows. (Fox, Personal Communication) Also, Knyff portrays the quarter gallery windows as rectangular. This was not the case when the

Sovereign was launched. Pett, Payne, and van de Velde all portray them as arched..

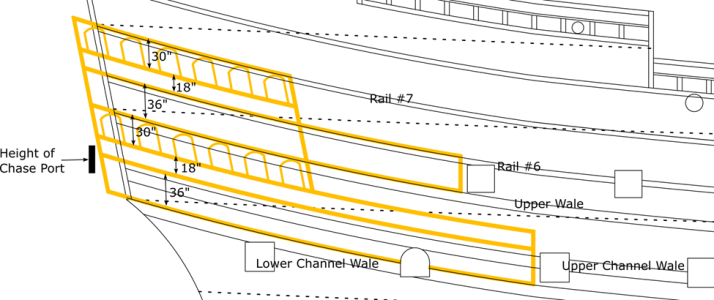

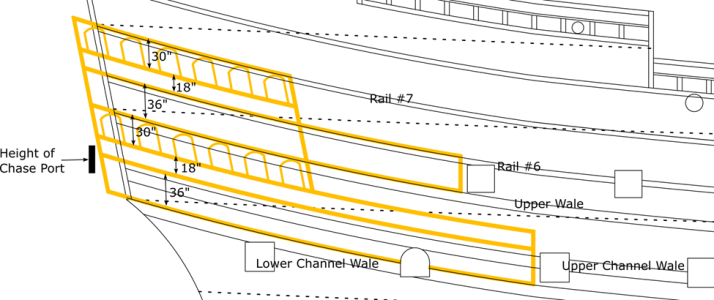

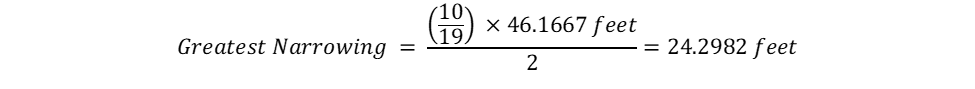

We can evaluate Fox’s suggestion by examining the spaces between the relevant wales and rails when we make the stern chase port’s size and height above the deck equal to those of the ports on the ship’s side, and employ the spacing between rails suggested by the Pett painting. This is shown in Figure 72. The figure also shows how this deck’s stern chase port aligns with the rails as they wrap around the stern. Under these conditions, rail 3B is cut by the chase gun port just as it is in the Knyff painting, and the height of the upper gun deck’s stern chase port above rail 3A is about equal to that port’s diameter, which is also like Knyff.

The discrepancy between Knyff and the Lely painting arises because the latter has placed the upper gun deck’s chase ports too low. Putting them so close to rail 3A also puts them too close to the upper gun deck. We can see that Lely has appropriately placed the rail at the quarter gallery’s floor (there are what appears to be gilded gallery supports below the rail), but this rail is immediately above the lower channel wale which, in turn, is also near the deck. Therefore, rail 3A in the Lely painting must also lie very near the upper gun deck. In fact, the painting suggests the chase ports are no more than 8 to 10 inches above it. As suggested by Figure 72, shifting the chase ports downward by about this much places them below rail 3B, but it is highly unlikely that the Sovereign was built with chase ports so close to the deck.

Putting the ports too close to the deck seems to be the only plausible way to make the stern look like the Lely Painting. When we attempt to do so by rearranging rails 3A and 3B, and simultaneously retain Pett’s flush decks and heights, we cannot place the port below rail 3B without substantially deviating from the gallery rail spacing suggested by both the Pett painting and the Payne engraving. For example, we must raise rail 3B by 16 inches just to clear the port, and then by an additional few inches to make room for the decoration surrounding that port. This compresses the space between rails 3B and 3C to almost nothing. The failure of these rearrangements to produce a satisfactory result is further evidence that it is incorrect.

McKay’s plans produce a stern that looks like the one portrayed in the Lely painting. To accomplish this, McKay had to erroneously place the stern windows higher than those that run along the quarter galleries. Ironically, the fact that he could only replicate the Lely painting by misplacing the stern windows is evidence that this painting is incorrect.

Figure 72. Schematic Representation of the Sovereign’s Stern and Gallery Rails

Note: “UGD” stands for upper gun deck. The upper gun deck’s top (shown in black) coincides with the top of rail 3A. All rails are two inches wide. Heights of one rail above another refer to the height of the top of one rail above the top of the rail just above it. There are 84 inches (7 feet) from the top of the lowest rail (rail 3A) to the top of the highest one (rail 5A). The height of the upper gun deck is show as the height of its aftmost end at the ship’s side. When compared to Knyff painting, the port drawn here appears disproportionately large with respect to the windows. However, Knyff portrays the lower tier of windows as somewhat larger than the ports along the sides of the upper gun deck, Both Pett and Payne portray the quarter gallery windows as about the same size of these ports. The implication is that Knyff’s windows are too large.

We can, however, make slight adjustments to the ports. The dimensions shown in Figure 72 leave only two inches between the port’s top and the bottom of rail 3C. This means there are only two inches of space for the decoration that surrounds the port. Some modelers may find this too small, and choose to reduce the port’s diameter by a few inches and/or reduce its height above the deck by a similar amount. Some modelers may also find that the rails shown in Figure 72 are too narrow (the figure depicts them as two inches wide). The rails can easily be widened a bit so long as the spacing between their tops remains as shown in the figure.

The rails for the upper quarter gallery, like those of the lower quarter gallery, wrap around the stern. The spacing between the rail tops of the upper gallery are the same as those as between the analogous rails on the lower quarter gallery (Figure 73).

Figure 73 Quarter Gallery Dimensions

Note: Rail heights are from the top of one rail to the top of the rail above it. All gallery rails are assumed to b 2 inches wide. The chase port “folded” across the rail that bisects it on the actual ship.

There are two more problems with the Lely painting. The first is that both quarter galleries are shown as horizontal. As discussed in the previous section, this is incorrect. The Sovereign’s galleries, like those of other ships of its time, sloped. The second is that the painting suggests the rudder head, and hence the tiller, is above the middle gun deck’s chase ports (see Figure 70). This does not conform to contemporary building practices, in which the tiller ran under the middle gun deck.

In summary, if we are to believe that the Sovereign had a square tuck stern, we must believe the Lely painting. It is the only evidence for such a stern, and it comes from only one side of the ship. However, this painting contains several errors, and leads to dimensions that are, at best, difficult to obtain. Believing that the Sovereign had a round tuck stern makes it like similar ships of this era. It seems more reasonable to use the Knyff painting, which also shows a round tuck stern, as a guide. A later drawing by van de Velde (see Figure 17) is also useful, though it must be used cautiously. [2]

There are two final details about the stern that deserve mention. Deane tells us that the “upright of the stern” (i.e., the stern’s upper part) should rake “something less” than the sternpost. The stern rake on the current plans is five feet, which qualifies as “something less” than the post’s rake of 8 feet. Also, and as previously discussed, notice that the Knyff painting shows that the stern galleries are rounded. This is contrary to many models of the Sovereign, which portray them as flat. The rounding cannot be seen in the Lely painting because it was made from directly behind the stern. The current plans draw the stern galleries as projecting two feet aft of the quarter gallery’s aft end.

References

Anderson, R.C. 1913. "The Royal Sovereign of 1637." The Mariner's Mirror 3 (6): 168-170.

Anderson, R.C. 1913. "The Royal Sovereign of 1637." The Mariner's Mirror 3 (4): 109-112.

Fox, Frank. 1980. Great Ships. London: Conway Maritime Press.

—Personal Communication

—Personal Communication

Goodwin, Peter. 1998. The Influence of Industrial Technology and Material Procurement on the Design, Construction and Development of the H.M.S. Victory. June. Vol. Thesis. Ann Arbor, Michigan: ProQuest LLC.

Howard, Frank. 1979. Sailing Ships of War 1400 - 1860. New York: Mayflower.

P, Mark. 2020. Sovereign of the Seas: Square Tuck or Round Tuck. Nautical Res

arch Guild. May 29. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://modelshipworld.com/topic/24438-sovereign-of-the-seas-square-tuck-or-round-tuck/.

van Duivenvoorde, Wendy. 2015. Dutch East India Company Shipbuilding: The Archeological Study of Batavia and other Seventeenth Century VOC Ships. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press.

[1] Another meaning of “tuck” relates to the rising line of the floor.

[2] The

Sovereign had been extensively modified by the time of van de Velde’s drawing. Part of these modifications involved removing the quarter galleries’ extensions, and replacing the original stern lantern with a smaller one. Notice that, unlike the Lely painting, the tiller on van de Velde’s drawing is correctly placed. Van de Velde also shows the lower row of stern gallery windows as square, which is like those shown by Knyff. The Lely painting shows them as arched. It cannot be determined whether this is another error in the Lely painting, or the result of a modification made after this painting was completed.

{I apoligize for this. This is another instance where the SOS site wants to put in an icon, and I can't prevent it. The word should be "sleepx", but without the "x")posed threats to property, the body, and the soul, not to mention the threats to getting sleep. William Herbert’s 1657 “A companion for a Christian containing, meditations & prayers, fitted for all conditions, persons, times and places either for the church, closet, shop, chamber, or bed: being seasonable and usefull for these sad unsetled times” speaks of "terrors, sights, noises, dreames and paines, which afflict manie men” at rest. (Ekirch 2001)

{I apoligize for this. This is another instance where the SOS site wants to put in an icon, and I can't prevent it. The word should be "sleepx", but without the "x")posed threats to property, the body, and the soul, not to mention the threats to getting sleep. William Herbert’s 1657 “A companion for a Christian containing, meditations & prayers, fitted for all conditions, persons, times and places either for the church, closet, shop, chamber, or bed: being seasonable and usefull for these sad unsetled times” speaks of "terrors, sights, noises, dreames and paines, which afflict manie men” at rest. (Ekirch 2001)