Pirate Lore, Myths & Legends #7 (Part l)

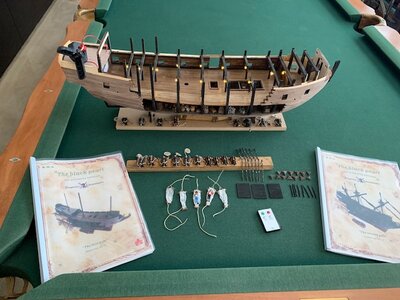

Since I am spending an inordinate amount of time making my own original and unique “look” for my cannons and accessories to the Black Pearl, I wanted to research the armaments that were common to these ships of the 1700’s. Now, please understand that my finished designs for my cannons which I will display in my next Captain’s Log, is much too ornate for Captain Jack Sparrow’s ship. However, my ship’s crew deserves nothing but the best and I’ll explain my reasoning for making them look like they came off a Royal Navy flagship inside my next log!

For now, let’s learn a little about the cannons that were likely used during the height of Piracy!

The Pirate Empire

Fascinating facts about Pirates, their lives, weapons, ships, and history, by the author of The Pirate Empire, available on Amazon.

Pirate Cannons and How They Work

“Run out the guns!”

A pirate vessel comes sailing over the horizon, and the crew of the merchant ship they approach cowers in terror. For not only is the deck swarming with pirates, waving pistols, swords and machetes, but along the vessel’s side, a row of ports open and the cannons are pushed out, ready to deal death to any who defy these robbers.

Cannons were one of the marks of a pirate ship. But how did these things work?

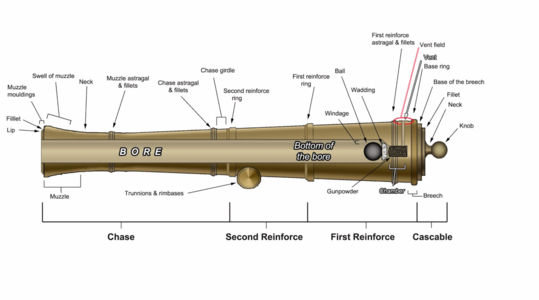

In the first place, not all cannons were the same. There was the matter of size. Naval guns during the Golden Age of Piracy were based, not on caliber, but on the number of pounds that the cannon ball weighed. Thus, you had a 4-pounder, a 6-pounder, and on up through the 12, 18, 24, 36 and 42 pound cannons. The only cannon with an odd-pound rating was the “long nine” a gun which was usually mounted to fire over the bow or stern of the ship, instead of directly perpendicular to the keel. It had a longer barrel to help give it a longer range.

Most of these sizes, however, were limited to huge naval vessels. Since most pirate ships were smaller, nimbler vessels, they rarely had weaponry rated at more than six pounds. We will discuss a six pound cannon for the rest of this article.

(An aside – why didn’t pirates have the very biggest guns in existence? In the first place, cannons took up space, and there was only so much space available on the ship. The pirates had to live and sleep somewhere. Heavier weapons also meant that, for the ship to float, she could take on less cargo or plunder. And there’s also the problem that, in order to get a 24-pound cannon, the pirates would have to take it away from someone who was already using it. Not an easy thing to do.)

Cannons at sea were most often of brass construction. Brass was lighter and did not corrode in salt air, as iron did. Cannon balls were iron. (Some folk have erroneously thought that the cannon balls were lead, like pistol and musket shot. But those weapons were intended for use against people, and cannons attacked oaken ships and stone forts.)

A 6-pound brass cannon weighed approximately 1200 pounds, including the gun carriage, the four-wheeled wooden “cart” that the cannon sat on. Range could be up to 1500 yards, but the round shot quickly wandered in its trajectory, and was very hard to aim at extreme range.

On a small ship, like a pirate vessel, guns were typically kept on the open deck, not on a specialized gun deck with gun ports. There simply wasn’t room below. Cannons were typically protected by canvas covers. Care of the guns was the business of the Master Gunner and his assistant, the Gunner’s Mate. The weapons took some damage themselves every time they were fired, and an improperly maintained gun was a greater danger to its crew that to the enemy. (For example, Henry Avery’s great prize, the

Ganj-in-sawi may have only fallen because one of her own cannons exploded on the deck, blowing a hole in the side of the ship and killing dozens of her crew.)

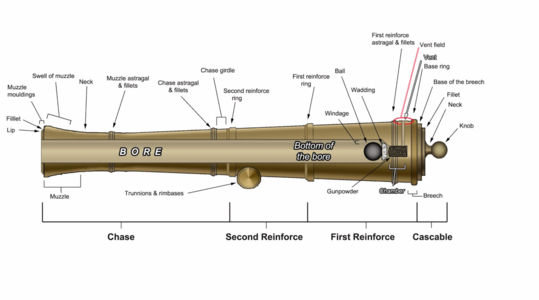

Cannons of the era were essentially long tubes made of brass, bronze or iron closed at one end. A small hole called a touch hole was drilled through the wall of the barrel near the closed end.

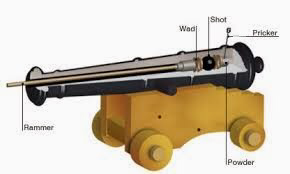

Loading and firing a cannon went as follows:

The powder had previously been carefully measured and packed into a canvas bag shaped to fit. These bags were stored in the powder room. During battle a crew member, carefully dressed in clothing and shoes that would not generate a static spark, stood in the powder room passing the bags to runners who carried them to the gun. This system minimized the chance of an accidental explosion. On navy ships these runners were often orphaned boys called “powder monkeys” who lived on the ship. Pirates almost never employed children, and used the less skilled members of their crews instead.

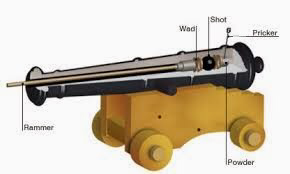

The load of gunpowder was shoved down the muzzle of the gun and pushed all the way in by a man with a tool called a rammer. Next a “wad” went in. This was a wad of cloth, oakum, cotton, or even old rags. Because of the unsophisticated manufacturing techniques of the time, the cannon balls did not fit tightly in the barrel of the gun. (Better to have the fit too loose than to make a cannon ball that was too big to fit.) The wad took up extra space, and guaranteed that the ball would leave the cannon with maximum pressure behind it.

The wad was also rammed into the cannon. The cannon ball went next. Our 6 pound cannon would take a ball of about 3 ½ inches diameter. This would probably roll to the back of the cannon, as the barrel of the gun was almost certainly elevated at an angle.

A pick was poked through the touch hole to rupture the bag full of powder, so fire could reach the contents.

Next the gun was run forward against the railing of the ship or poking out the gun port. It was aimed, usually by the gun captain, the leader of the gun crew, or group that serviced this particular cannon. Gun crews were assigned to a particular cannon, as each had its own peculiarities, and it was best for a crew to be as familiar as possible. Aiming had to take into account the pitch, roll and yaw of the ship, as well as wind, wave and the movement of the enemy vessel. It was one of the most difficult jobs on a ship. And yet gun crews, in practice, could achieve amazing accuracy.

At the right moment, the gun captain called to yet another man who was standing by holding a tool with a lighted fuse on the end of it. This fuse was made of a substance called “slow match” which, as the name says, burned very slowly, at the rate of about a foot an hour. This slow match was held on the end of a long stick. This was the original “fire in the hole.” The man using it could stand back, away from the rear of the cannon, and apply the burning match to the touch hole, where it met the gun powder.

Immediately two thing happened. The cannon ball and wadding shot out the barrel of the cannon, and the gun itself leaped backward. (For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.) Of course the gun was restrained, by heavy ropes so it could not go too far. But the recoil-driven movement was necessary, for it brought the cannon back away from the side of the ship, putting it into position to be loaded again.

There was one more thing, however. The last member of the gun crew, the sponger, needed to do his job. Dipping a sponge, on the end of a pole, into a nearby bucket of water, he would sponge out the inside of the gun, cleaning out any power char or burning wadding, making it safe to put powder back into the gun.

Repeating this process, over and over, on a crowded deck while taking fire from an enemy vessel, was dangerous, nerve wracking, and exhausting. The team needed to work together, and every man had to do his job. Many things could go wrong. If the gun was incorrectly sponged out, the fresh load of gunpowder might explode prematurely. Cannonballs might fall to the deck, rolling and becoming a hazard. The back might blow off the gun, if the area around the touch hole had become worn or corroded. Or the gun might break loose from the ropes holding it, becoming a 1200 pound wheeled death wagon.

The saying “loose cannon” comes from this. On the deck of a moving ship, the cannon might move in any direction, destroying everything around it, crushing men, breaking the feet of anyone it rolled over, and possibly even punching right out the side of the ship that held it. The only way to contain it was to re-rope it and tie it down, risking being run down.

All of this, of course, was why merchant ships usually gave up without a fight.

The most dangerous

pirate ships were those with several mounted cannons - ideally, at least ten. Large pirate ships, such as Blackbeard's

Queen Anne's Revenge or Bartholomew Roberts'

Royal Fortune had as many as 40 cannons on board, making them a match for any Royal Navy warship of the time. Cannons were very useful but somewhat tricky to use and required the attention of a master gunner. They could be loaded with large cannonballs to damage hulls, grapeshot or canister shot to clear decks of enemy sailors or soldiers, or chain shot (two small cannonballs chained together) to damage enemy masts and rigging. In a pinch, just about anything could be (and was) loaded into a cannon and fired: nails, bits of glass, rocks, scrap metal, etc.

Accessories:

Shot:

In addition to varying shot weights, different types of shot were employed for various situations:

Round shot: Solid spherical cast-iron shot, the standard fare in naval battles.

Canister shot: Cans filled with dozens of musket balls. The cans broke open on firing to turn the gun into a giant shotgun for use against enemy personnel.

Grapeshot: Canvas-wrapped stacks of smaller round shot which fitted in the barrel, typically three or more layers of three. Some grape shot was made with thin metal or wood disks between the layers, held together by a central bolt. The packages broke open when fired and the balls scattered with deadly effect. Grape was often used against the enemy quarterdeck to kill or injure the officers, or against enemy boarding parties.

Chain-shot: Two iron balls joined together with a chain. This type of shot was particularly effective against

rigging, boarding netting, and sails, since the balls and chain would whirl like

bolas when fired.

Bar shot: Two balls or hemispheres joined by a solid bar. Their effect was similar to chain shot.

Expanding bar shot: Bar shot connected by a telescoping bar which extended upon firing.

Link shot: A series of long chain links which unfolded and extended upon firing.

Langridge: Bags of any junk (scrap metal, bolts, rocks, gravel, old musket balls, etc.) fired to injure enemy crews.

Fire arrows: A thick dartlike incendiary projectile with a barbed point, wrapped with pitch-soaked canvas which took fire when the gun was fired. The point stuck in sails, hulls, or spars and set fire to the enemy ship.

Heated shot: Shore forts sometimes heated iron shot red-hot in a special furnace before loading it (with water-soaked wads to prevent it from setting off the powder charge prematurely). The hot shot lodging in a ship's dry timbers would set the ship afire. Because of the danger of fire aboard, heated shot were seldom used aboard ships.

Molten iron shell: A variation on heated shot, where molten metal from a furnace is poured into a hollowed out shell and then allowed to cool briefly to seal the molten metal in before firing.

HMS Warrior (1860) was outfitted to fire molten shells.

Double shot: Two round shot or other projectiles loaded in one gun and fired at the same time. Double-shotting lowered the effective range and accuracy of the gun, but could be devastating within

pistol shot range; that is, when ships drew close enough for a pistol shot to reach between the two ships. To avoid bursting the gun, reduced powder charges were used. Guns sometimes were double-shotted with canister or grape on top of ball, or even triple-shotted with very small powder charges which still were enough to cause horrible wounds at close range.

Exploding shell: Ammunition that worked like a grenade, exploding and sending shrapnel everywhere, either by a burning fuse which was cut to a calculated length depending on the range, or (after 1861) on contact with the target. Shells were often used in mortars, and specialized and reinforced "

bomb vessels" (often

ketch-rigged so that there was less rigging to obstruct the high-angle mortar shell) were adapted to fire huge mortars for shore bombardment. The "bombs bursting in air" over

Fort McHenry in the

American national anthem were this type of projectile.

Gun Crews:

Gun crews consisted of between a minimum of seven and a maximum of fourteen men around the gun. They consisted of the following:

Gun Captain: Fired the gun and assisted in its handling during combat.

Second Captain: Would normally act as a gun captain on the opposite side of the ship the gun captain was working on, if both sides of the ship were engaged.

Loader: stood to the left of the muzzle, and would load the gun with cartridges and shots, and wads.

Gun Crew

Assistant Loader:Stood behind the loader, and would pass him wads and shots.

Sponger: Stood to the right of the gun muzzle, and rammed cartridges and shots down into the gun chamber with the rammer, as well as cleaned the gun vent with the worm, and sponged the inside of the gun down to extinguish stray sparks.

Assistant Sponger: Handed the sponger his tools in combat, standing directly behind him.

Handspike Man 1 and 2: These two stood behind the gun to the right and left. They elevate and depressed the gun using their handspikes, or giant wooden crowbars, and also levered the gun left or right.

Powder Carrier: Usually younger boys, they would hand the cartridge over to the loader, as well as run down to the magazine, retrieve a new cartridge, and bring it back up to the gun in order to keep the flow of powder moving in battle.

Auxiliaries: There were normally five auxiliaries, who stood on either side of the gun, and would haul on the side tackles to move the gun forward and point the muzzle out of the gun port.

Well mates, this info may not be specific to just a Pirate ship, but nonetheless, ship battle was not for the faint of heart! We will continue with Part ll in the not too distant future.

Ahoy all!