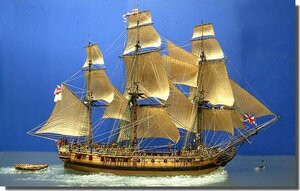

Hi Bonden, you have an amazing build also! I’ve yet to comment there but am meaning to have a proper read from the start. I worked on the Endeavour replica for a number of years and keep with the colours used on her upper works regarding the blue, red and bright yellow for the trim work. Endeavour is tarred however on the upper hull between the wale and trim rather than painted yellow. This is most likely as she was a small ship and the decorations and paint was usually subsidised by the captain. Cook wasn’t the wealthiest of men at this time so it would have been unnecessary to paint her upper works yellow.

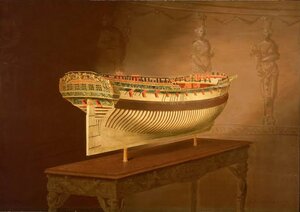

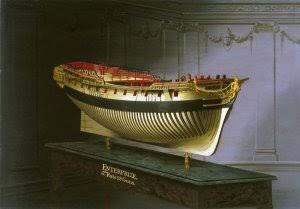

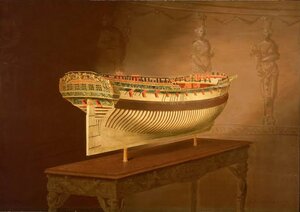

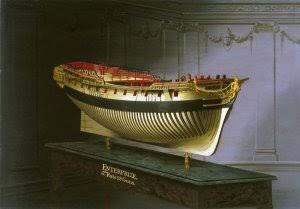

I have to admit the NMM models have affected my choice with including the frieze on Mercury as well as the painting of the model of HMS Enterprise the lead and name ship of the class

It’s most likely though if Mercury has any frieze world painted it would have purely been at time of launch and painted over with the blue in fashion.

Paint was used more widely to decorate vessels in the 18th century than in any previous age. The raw materials necessary were available in sufficient quantities to allow the preservative properties of paint to be put to good use and they were usually mixed on the spot from the component pigments, oil, and thinner. English dockyards commonly used white lead, vermilion, red ochre, spruce (Prussian ochre), English ochre, verdigris (used for greens), calcined smalt (a cobalt compound used in blues) and blue-black. Gold leaf was also used, though sparingly, as were red lead, Venetian red, and Indian red. The Venetian and Indian reds would have been used for small decoration rather than mass coverage. A drab paint was made by mixing the leftovers together and was known, appropriately, as ‘sad colour’. It was used on the bottoms of boats, in the bilges, and on the faces of joints. In the 1780s whitewash began to be used on the interior parts of ships and its application gradually increased until it had, to a large extent, replaced the traditional red (Howard 1979:194) I’ve opted like in the Endeavour replica for these parts to be red and white wash only in the great cabin.

According to an Admiralty Order of 1715, the sides of ships were to be ‘painted of the usual colour yellow, and the ground black, and that both inside and out to be of a plain color ... except such parts of the head, stern, and galleries as are usually friezed...’ The ‘usual colour yellow’ implies a well-established tradition, and there is evidence that the Order was obeyed. Many contemporary pictures and models do not agree with what is stated in the Order, as they depict the sides ‘bright’, which means that they have been treated with turpentine or tar. Varnish and salt air and sea water for that matter, do not agree with each other especially for a ships side. I sailed a number of voyages on the Duyfken replica around Australia and further afield, and one job we always had was to scrape off the varnish that was applied when the replica was built and to be tarred over. You never wore any fancy clothes living on Duyfken as you would either end up covered in Stockholm tar or tallow! Haha

The upperworks of some models are a soft, light blue on which scrollwork and heraldic designs are painted in gilt, and others, although conforming to the Admiralty Order about plain colors, nevertheless have scrollwork in gilt along their topsides. This divergence from the official scheme suggests for certain that the artists took some amount of “artist’s license’ when decorating the contemporary models we see at NMM and the Science Museum. After 1740, there is no doubt about individual variations in ships’ paintwork, for there are references to ships with all-black sides (which would make them look smaller and, so it was hoped, induce the enemy to attack) and to others with the lowest wale and the topside black but the portions in between painted red.

The history of ship painting for the years 1740-1780 has never been investigated in detail but enough information has come to light to prove that the appearance of a fleet then was far from uniform. Official recognition of this fact was given in an Admiralty Order of 1780 that allowed ships to be painted black or yellow, and from then until some years after Trafalgar a fairly wide variety of styles was to be seen. A record of the appearance of the British ships at the Battle of the Nile in 1798, made by Col. Fawkes, who was present at the battle, is indicative of this “mottled” fleet (Howard 1979:193):

1. Plain yellow sides: Alexander, Audacious, Bellerophon, Defence, Orion, Mutine

2. Yellow sides with a black strake between the upper and lower rows of gunports:

Goliath, Leander, Majestic, Theseus, Swiftsure, Vanguard

3. Yellow sides with two narrow black strakes between the upper and lower rows of gunports: Culloden

4. Red sides with a small yellow stripe: Zealous

5. Red sides with a black strake between the upper and lower rows of gunports:

Minotaur

Eventually the realisation that heavily ornamented warships were a handicap in sea battles must have hastened the steady reduction in the amount of artistic embellishment which had characterized the appearance of warships after 1700. Figures gradually gave way to merely ornamental patterns. More stress was laid on beadings, friezes, emblems, and cartouches. Figures were confined to smaller sculptures of dolphins, masks, and cherubs, while the only larger ones were those of the figurehead and coat of arms. This development was parallel to and linked with a reduction in the size of the after-castle, which naturally reduced the size of the surface on which ornaments could be applied. The process of elimination continued through the 18th century until all that was left in the way of ornamentation was the figurehead, coat of arms, and name symbols (Hanson 1968:122).

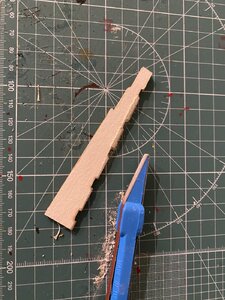

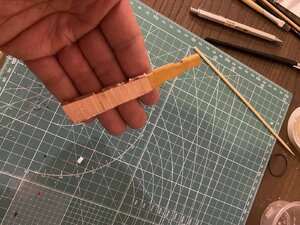

So from my little research into the history, I’ve opted my route but again I just find that frieze captivating. I’m still on the fence as to whether to stain the lower planks - between the copper and the wale - in a tarred brownish black as found on the Pandora and some other ships of the period.

Oh and Bonden, I understand completely what you mean so don’t be put off by your translation.