- Joined

- Dec 1, 2016

- Messages

- 6,426

- Points

- 728

After thinking about tool for the beginner i get Harold Hahn reasoning why he would never allow his work to be turned into a kit. His idea was to teach those who wanted to build model ships by using his plans and research and learning how to use woodworking tools. I also see why kits are designed the way they are and can be built with the minimum number of tools. A kit that required twice the cost for tools to enable you the build the model is not a good idea. There are levels to this hobby and the beginner should start with a beginner's kit to see if the hobby is something you want to continue with.

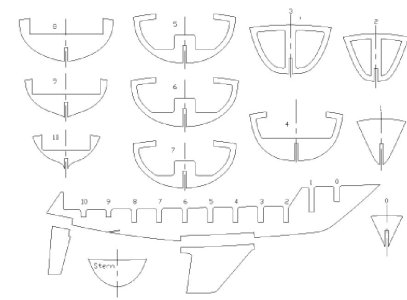

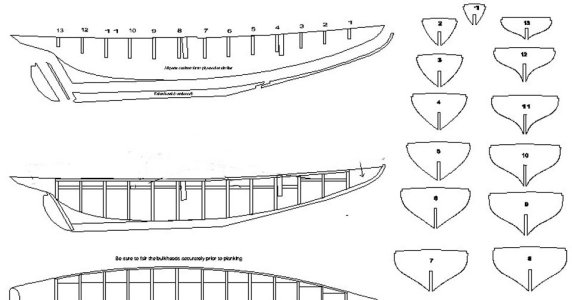

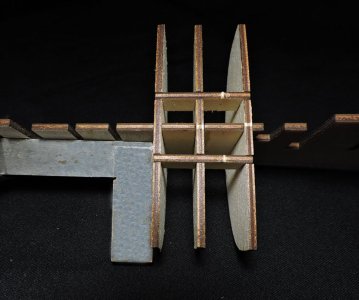

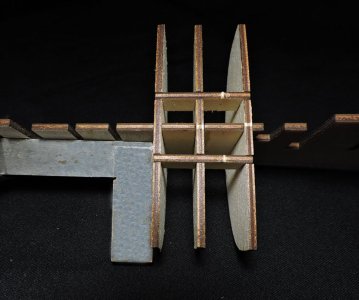

To assemble the bulkhead structure all you need is a square or something around the house that is square

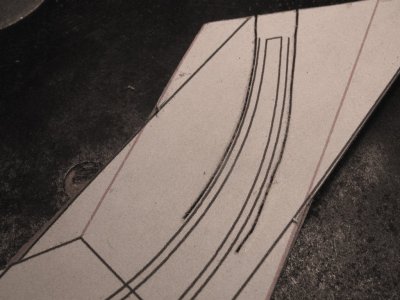

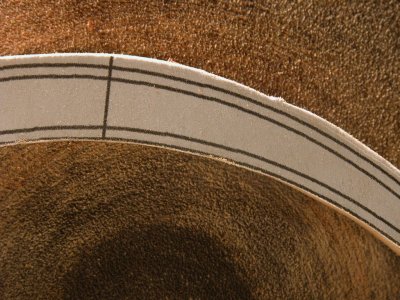

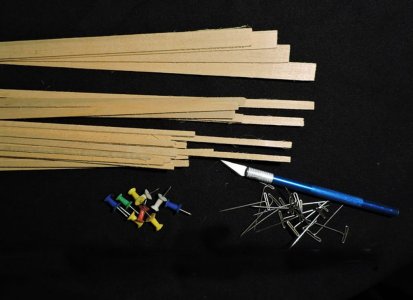

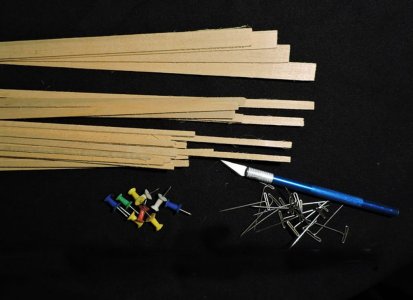

Many of the kits supply one width of planking when actually you need wide planks for a garboard and bottom planks and narrower planking for the upper works. Hull planking is shaped to fit the hull and with only one width of planking creative use of stealers are used. What you will need is a knife and push pins oh yes and a woodworking glue.

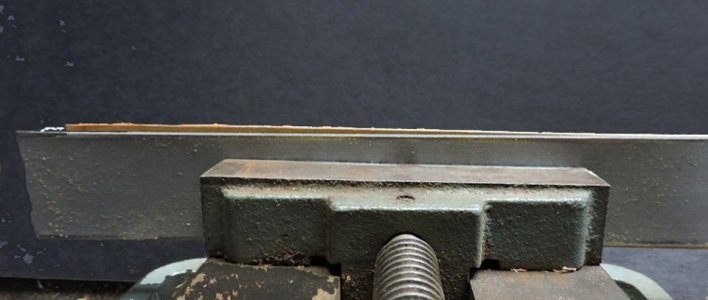

Push pins are ideal for holding planks in place while the glue sets.

by pushing the pin in tight to the edge of the plank holds it against the last plank and holds it down

if you want the pin to reach a little more into the width of a plank a small washer works just fine.

To assemble the bulkhead structure all you need is a square or something around the house that is square

Many of the kits supply one width of planking when actually you need wide planks for a garboard and bottom planks and narrower planking for the upper works. Hull planking is shaped to fit the hull and with only one width of planking creative use of stealers are used. What you will need is a knife and push pins oh yes and a woodworking glue.

Push pins are ideal for holding planks in place while the glue sets.

by pushing the pin in tight to the edge of the plank holds it against the last plank and holds it down

if you want the pin to reach a little more into the width of a plank a small washer works just fine.

Last edited: