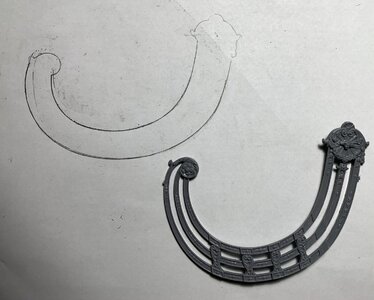

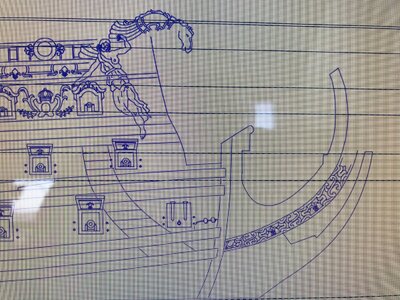

So, the process of making this first starboard bracket has been highly educational! Anytime I’m making a part like this, I am designing a process to arrive at a level of detail with the least amount of difficulty. For these brackets, one of the primary details that I wished to capture is the pierced filigree of the false canopy. This, much like the trailboard at the head, can only be arrived at through careful piercing and paring, from one side to the other and back again.

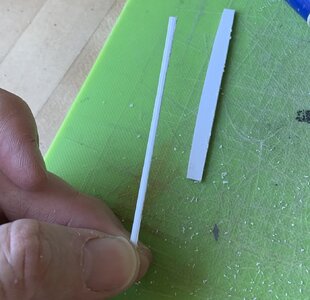

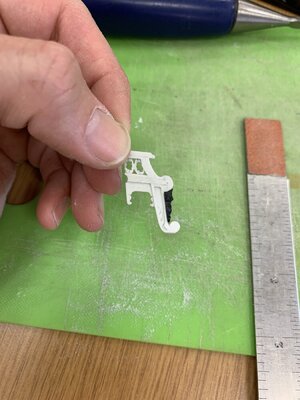

As always, though, I like cleanly delineated shoulders and panel reliefs, so I thought it would make the most sense to build the bracket up from three primary layers of .028 styrene sheet which, I will show later, gives me just nearly enough part thickness to mount the Four Winds mascaroon. Carving the filigree into a larger supporting lamination is far easier than carving it as an independent insert piece.

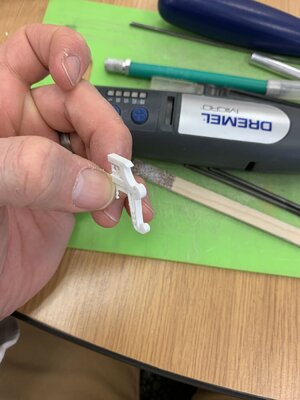

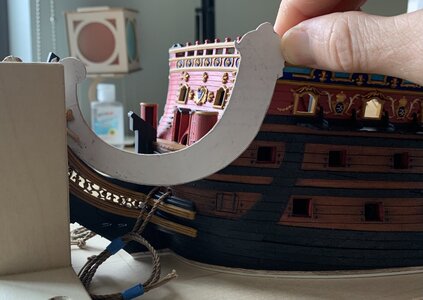

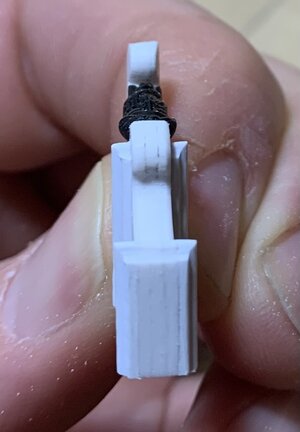

Above, I’ve already carved the filigree and laminated the aft layer to the center. The edge that joins with the hull is also about a 1/32” oversize, to allow for precise scribing to the hull, a little later.

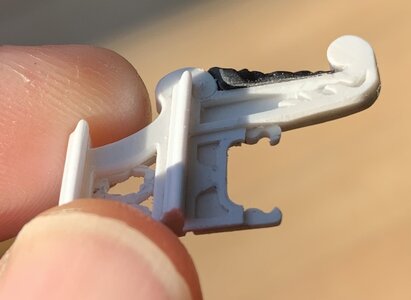

The bottom of the scroll, where it mounts to the bulwark rail, has been left deliberately overlong for final shaping, once the three layers have been laminated together. I was mindful, at this stage, that the back-raking angle of the bracket would necessitate a raking angle for the scrolled foot, as well; were I to shape each lamination to size, before gluing, I would end up with a significant gap, at the forward face of the foot.

After lamination and initial scribing to the hull and gallery rail, the foot looks like this:

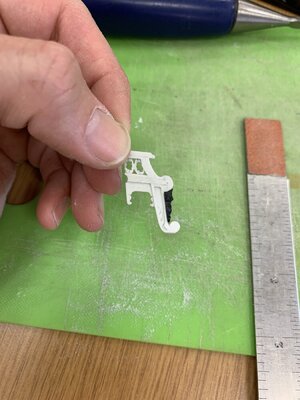

With the bottom angle of the foot established, I could proceed with shaping the scroll and fairing the leg to it’s final form. Here is a montage that shows the evolution of this process:

One thing I have found to be true; it is much easier, at times, to “draw” with the tools, than it is with a pencil. I was able, for example, to emphasize an elegant sloping transition into the foot with my files and a sanding stick. Now, when I position the bracket on the model, the negative space of this archway is at a more complementary angle to the adjoining windows than my initial drawing/template.

It’s a little hard to read in the following picture, but I have introduced a slight taper to the scroll foot from bottom to top; this is the first step along the detailing path of a scrolled volute. I will show the relief work, in this area, in the next post, after I have attached the acanthus brackets.

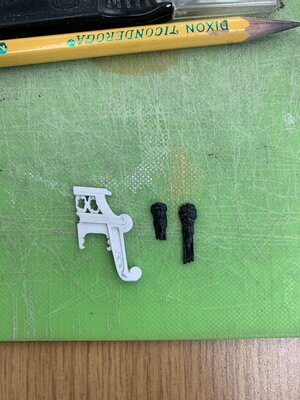

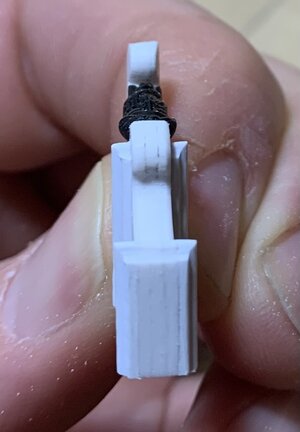

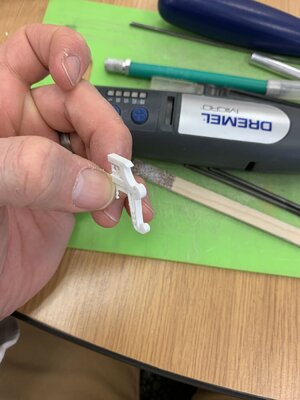

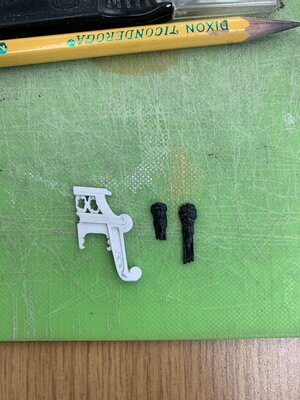

So, with this much established, I could focus on fitting the mascaroon that I had retrieved from the kit quarter gallery. Given the difficulty of carving convincing faces, it is always worthwhile to see whether one can salvage the kit sculptures. The mascaroons are oversize, but I thought I could make it work.

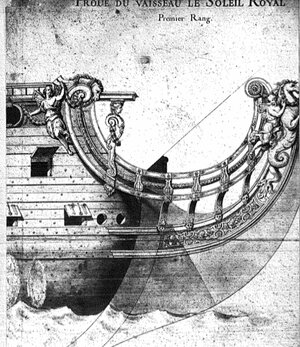

What I am trying to achieve:

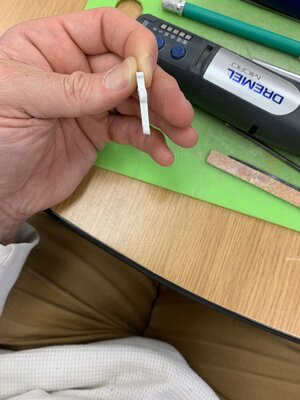

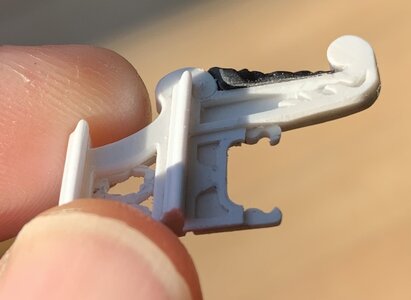

After much fettling, the mascaroon pares down quite a bit from where it began:

Now - the head is unavoidably wider than the bracket, but I will show a little later how simply softening these hard edges makes the sculpture look more like a deliberately rounded relief. I was able to retain just enough of the headdress, so I consider this sculpture experiment a success!

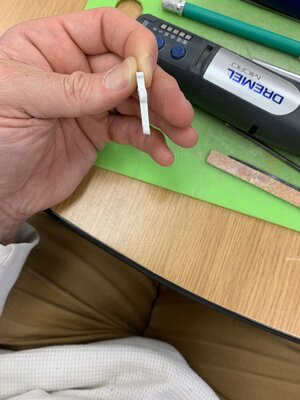

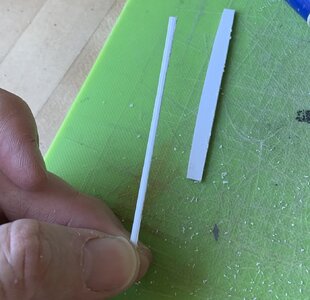

Next, I turned my attention to the mouldings which are really just a continuation of the top and bottom rails of the upper gallery bulwark. My idea was to simply profile a piece of scrap 1/16” styrene and then “rip” the moulding off the blank:

After truing the back edge, it was a simple task to profile the ends and secure them to the bracket:

This approach results in a generous perch for the seated figures:

I am currently adding-on the final layer of appliqués: paneled headers, bell flower escutcheons, filigree accents,

and acanthus brackets.

Here you can see how softening hard edges helps turn a shortcoming into an advantage:

Honestly, I don’t think I can do a better job of satisfying the design and artistic challenges of this complicated part. Nevertheless, it did dawn on me that my approach resulted in a fundamental architectural flaw that would never have found its way onto the actual ship. Can anyone spot it?

I’ll give you all a little time to mull it over, and then I’ll explain why it won’t matter for this model, and is not worth the monumental effort of remaking the part. I got lucky, this time, but the insight has only deepened my appreciation for these 17th C. shipwrights who managed to knit the whole structure together seamlessly.

As always, thank you for your support! More to follow..

BONUS PIC of where things stand today, a week after I wrote this post for MSW:

The narrower arch now gells with the panel below.You could take it even further by reducing the width of the pillar at the top but leaving the arch as is.This would reduce the width of the blue inlay but that would not look out of place given the width of the inlays running below this pillar.

The narrower arch now gells with the panel below.You could take it even further by reducing the width of the pillar at the top but leaving the arch as is.This would reduce the width of the blue inlay but that would not look out of place given the width of the inlays running below this pillar.