Good morning everyone. I am at work, only to hear that my first two classes had been cancelled because my student had to take her child to hospital. At best this is frustrating, because the two hours wasted are precious to me (heck, I could have spent it in the shipyard

), but life gets in the way sometimes.

However, the upshot of this is that I can share you with the story of Sampan Annie. The story appeared on the following website

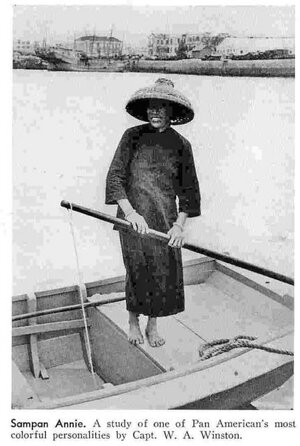

Sampan Annie-August 1941 | Gwulo: Old Hong Kong and was written by W.B. (Shorty) Greenough - Pan American Airways Chief Mechanic-Hong Kong. This essay was published in the form of a letter to the editor of Pan American Airways in-house magazine ‘New Horizons’ edition dated September 1941. (I have edited it to make it more readable and also to clarify some inaccuracies (the BOAC and Pan-Am personnel sometimes made the incorrect distinction between junks and sampans).

SAMPAN ANNIE

Family Name: Chin Yun Gi

Nickname: Sampan Annie

Sex: Female

Status: Deceased

Birth Date: c.1884-01-01 (Year, Month, Day are approximate)

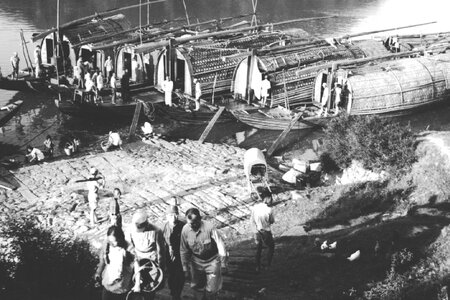

In Hong Kong, shipping has always been serviced by “sampan girls” particularly naval ships which often had their hulls repainted by teams of these women in exchange for left-over food and scraps. However, few are aware that at least one sampan girl also serviced flying boats. One little known fact about “Annie” is that her real name is Chin Yun Gi. Better known, in Hong Kong at least, is her status as head of a family group which numbers at least 35 or 40. Family ties are sacred and family traditions are reverently observed in China, as is well known. In the case of Annie’s family, it is one of those floating groups which are so numerous at Chinese seaports and along Chinese rivers. Thousands of Chinese know no other home than the fishing boats on which they are born, live their lives, and die.

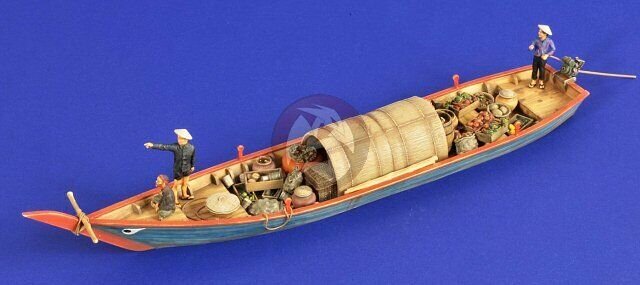

The sampan is the principal vessel from which Sampan Annie directs the lives of her family. It has always been her custom when a son gets married to buy him a boat; thus, there are now four sampans equipped for fishing. As each of the foregoing vessels is equipped with a small sampan in the order of a row boat, the fleet has nine units in all.

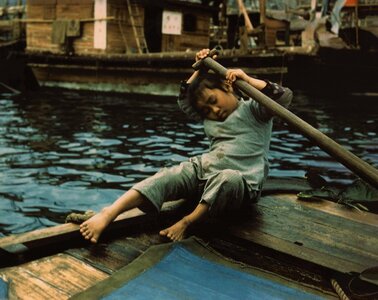

Annie’s immediate family consists of her husband, five sons and three daughters. The others are son’s wives and children. Some of Annie’s own children are about the same age as the grandchildren; she, herself, is about 65 years old. Fishing has been the family’s occupation and means of livelihood for many years; and, of course, it was Annie’s years of experience with the fishing boats which gave her the skill with sampans for which she is noted.

She got into the airline business when CNAC was operating amphibian airplanes in and out of Hong Kong. When CNAC changed over to land operation, Annie’s job was threatened. We needed a boat man and Annie was eminently qualified, so we quickly made a deal. She was to get Hong Kong $20 a month; and although this amounts only to about $5 in American money, it was entirely satisfactory to Annie.

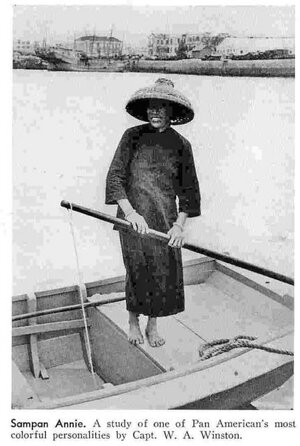

Annie’s invariable costume is a black suit comprising trousers and jumper of black coolie cloth, and a huge basket-like coolie hat. Aboard her sampan she is always barefooted, but when going ashore she may wear shoes which consist either of a piece of auto tire or a piece of board with a strap. The black costume is exactly like that worn by thousands of other Chinese women in sampans. It must be comfortable because it is so loosely fitted. In fact, it is my impression that those suits come in one size only, that being the largest.

When Annie first came to work for us, she brought her own sampan along. It is operated by a sculling oar being directed over the stern of the boat and moved from side by side like the tail of a ship. The skill with which Annie gets around a Clipper, passing a line to the officer in the bow, getting breast lines and tail lines into place and warping the Clipper up to the dock, is nothing short of amazing.

One of the stories about Annie, that gained wide circulation in the American press, happened about three years ago. Annie supervised the work of mooring a Clipper after its arrival on Saturday morning and then requested permission to leave early. This request was granted on condition that she would be back on the job early the next morning for the Clipper’s departure. To everyone’s surprise Annie was late in arriving. Annie’s loyalty and dependability are such that tardiness for her was just unthinkable. Then it came out that the reason she had wanted Saturday afternoon off was to give birth to her latest offspring. I can vouch for that story because it was I who gave her permission to go, and Mrs Greenough later went over to see Annie in the junk.

Annie’s proudest possession is the PAA Flight Engineer’s button which she sometimes inadvertently wears upside down. After her work has been done, she exercises what has become her prerogative of collecting every bit of food that remains in the galley, and then stages an impromptu picnic for whatever members of the family that happen to be along. On her own sampan she is the family provider, not just for sons and daughters but for the whole clan. They all help with the fishing and other work of course, but she directs everything. She buys the rice, the pork, Macao cabbage and spinach. Fish caught by the family is a regular feature of the menus. All the food is cooked on the mother boat to which all member of the family come at mealtime.

Shortly after this tale was published in September 1941, war arrived in Hong Kong in December. Annie and her family melted into the fishing community and got on with their lives.

On 11 January 1970, Pan American Airways ground-breaking Boeing B747 Jumbo Jet arrived for the very first time in Hong Kong. The next morning the South China Morning Post published a photograph of its 48-year-old Captain William Saulsbury, veteran of 22,000 flying hours, accepting a scroll from the diminutive 86-year-old Sampan Annie.