You certainly have your work cut out for you. It's coming along too! Working with oak has its challenges huh? Are you using white oak or red oak? I'm looking forward to seeing your progress!With the ugly things like shipworm now out of the way, it's time for my think-tank again on why I am struggling so much with my planking all of a sudden.

View attachment 322200

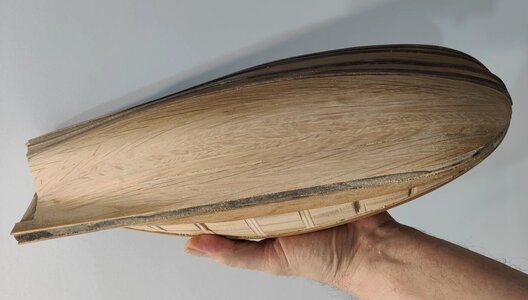

As a reminder, here is Willem Barentsz #1 in all her glory. Sure, the planking was a challenge, but nothing like what I am experiencing now. Which begs the question: What is different? Sure, the oak is more difficult to work with, but it has nothing to do with how the hull lines run or with interpreting the hull lines. The answer is actually simple, The WB #2 is built so different to #1 that I cannot expect to follow the same procedure and then expect it to work.

View attachment 322201

From the red line to the stern, the two hull shapes are essentially identical, but look at the two bows.

Close-up

View attachment 322203

Just look how much rounder and wider WB#2 (on the left) is at the bow compared to WB #1. There is a lot more space at the bow and like I said to Ab last night, it might just allow me to install the winch in the same position that he did. But that wide, round and more spacious bow comes at a huge expense when it comes to the planking.

-

Win a Free Custom Engraved Brass Coin!!!

As a way to introduce our brass coins to the community, we will raffle off a free coin during the month of August. Follow link ABOVE for instructions for entering.

-

PRE-ORDER SHIPS IN SCALE TODAY!

The beloved Ships in Scale Magazine is back and charting a new course for 2026!

Discover new skills, new techniques, and new inspirations in every issue.

NOTE THAT OUR FIRST ISSUE WILL BE JAN/FEB 2026

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

HIGH HOPES, WILD MEN AND THE DEVIL’S JAW - Willem Barentsz Kolderstok 1:50

- Joined

- Jan 9, 2020

- Messages

- 10,566

- Points

- 938

Thank you, Johan, I am very glad that you found it interesting. By the way, on the pics that I have posted of the two bows of the ships, you will see that WB #2 is much more in line with what you suggested all along.Very informative, thanks for sharing Heinrich.

- Joined

- Jan 9, 2020

- Messages

- 10,566

- Points

- 938

And don't forget WB #2 versus Heinrich - a battle which is solidly weighed in favor of the little ship at the moment!Another great history lesson, questions with no answers and answers without questions. Worms versus shipwrights and shipwrights versus worms.

- Joined

- Jan 9, 2020

- Messages

- 10,566

- Points

- 938

Yes, Phil - that I have. To me it looks like white oak. What is so frustrating is that I am probably about one-and-a-half strake away from closing the hull on the Starboard side, and now she throws her curveball at me. I just cannot figure out how to close that gap satisfactorily. With the walnut no problem - I have already checked that - with the oak, it's a different story.You certainly have your work cut out for you. It's coming along too! Working with oak has its challenges huh? Are you using white oak or red oak? I'm looking forward to seeing your progress!

Can you make a pattern with some card stock - to fit to get a template to follow for bending? Just thinking....?Yes, Phil - that I have. To me it looks like white oak. What is so frustrating is that I am probably about one-and-a-half strake away from closing the hull on the Starboard side, and now she throws her curveball at me. I just cannot figure out how to close that gap satisfactorily. With the walnut no problem - I have already checked that - with the oak, it's a different story.

- Joined

- Sep 3, 2021

- Messages

- 5,197

- Points

- 738

The shape of your WB #2 build in the bow area makes actually a lot of sense, especially when compared with it’s full size replica cousin, as in Harlingen.Thank you, Johan, I am very glad that you found it interesting. By the way, on the pics that I have posted of the two bows of the ships, you will see that WB #2 is much more in line with what you suggested all along.

I

My Vasa shared the bluff bow problem you are now encountering. Nigel's solution was spiling but you'll need a large enough piece of oak.

Begin here: https://shipsofscale.com/sosforums/threads/vasa-1-65-deagostini.5904/post-140102 for a reminder of my experience.

Begin here: https://shipsofscale.com/sosforums/threads/vasa-1-65-deagostini.5904/post-140102 for a reminder of my experience.

- Joined

- Jan 9, 2020

- Messages

- 10,566

- Points

- 938

That makes sense Johan as Gerald de Weerdt (master shipwright of the replica ship) has actually deviated from his own initial plans by following much more closely Ab's hull design.The shape of your WB #2 build in the bow area makes actually a lot of sense, especially when compared with it’s full size replica cousin, as in Harlingen.

I

- Joined

- Jan 9, 2020

- Messages

- 10,566

- Points

- 938

Thank you for this Paul. I believe this is what I am already doing (see plank below).My Vasa shared the bluff bow problem you are now encountering. Nigel's solution was spiling but you'll need a large enough piece of oak.

Begin here: https://shipsofscale.com/sosforums/threads/vasa-1-65-deagostini.5904/post-140102 for a reminder of my experience.

This has brought me to where I am now. My issue is that I am not doing this with veneer but with 1.5mm thick Oak which has to accommodate the compound curve within a 15-inch length.

I know what it's like to do that with walnut, but oak WOW. I also know what it is like to spend an hour on one strake then break it just before its ready. Very frustrating however when you finally have sucess it's such a reward.Thank you for this Paul. I believe this is what I am already doing (see plank below).

View attachment 322265

This has brought me to where I am now. My issue is that I am not doing this with veneer but with 1.5mm thick Oak which has to accommodate the compound curve within a 15-inch length.

- Joined

- Jan 9, 2020

- Messages

- 10,566

- Points

- 938

You are right my friend. I just have to keep my head down and keep trying,I know what it's like to do that with walnut, but oak WOW. I also know what it is like to spend an hour on one strake then break it just before its ready. Very frustrating however when you finally have sucess it's such a reward.

Well Heinrich that was very interesting and educational, thanks for posting it.Hello Dear Friends. Today was the first day where I just walked away from the build. I have struck the proverbial brick wall with my planking - nothing that I try, works - and I can assure you, I have tried very hard. So, time for a break.

Much has been said about the planking of Dutch ships and the one overriding fact that we always seem to return to, is the lack of format, logic or pattern. I have thus compiled a through report on exactly how the Willem Barentsz was planked, how we came to know it and how it compared to other ships of that era. The information all comes from my Bible, Het Schip van Willem Barents by @Ab Hoving Ab Hoving. Additional information was kindly supplied to me by Ab as well. The report may be a bit technical and long for some, but if you truly want to know about the planking of Dutch ships of the Sixteenth Century and why I deem the WB to be such a fascinating build, this is it! I call it:

DISCOVERY, DOUBLE-LAYER PLANKING, DOUBLING, THE FRONT-RUNNER OF HULL COPPERING AND TEREDO NAVALIS

In 1979, Russian amateur archeologist, Dmitry Kravchenko, found the wooden construction as part of a ship’s hull while searching for artifacts in and around Het Behouden Huys. He produced a drawing of his find, but because of the extremely difficult circumstances under which he had to work, it could best be described as “rudimentary”. Kravchenko left behind everything that he had found, untouched and in their exact original location and positions. Seemingly, the “discovery” then went into a thirteen-year long hiatus in which no further mention of it was made. In 1992, a Russian expedition led by Peter V. Boyarsky of the Russian Research Institute for Cultural and Natural Heritage arrived in Nova Zembla.

Interestingly, Boyarsky’s research did not focus specifically on finding artifacts connected to the WB expedition – it was a comprehensive mission (which included archeologists, ecologists, geologists and representatives of various other disciplines) – aimed at achieving a global picture of Nova Zembla which they viewed as a National Park of sorts. Be that as it may, they “re-discovered” Kravchenko’s find and deemed it significant enough to take back with them to Moscow.

View attachment 322169

The discovered hull portion of Willem Barentsz's ship.

Six months later, a Dutch delegation comprising of Henk van Veen (Chairman of the Willem Barentsz National Committee), Pieter Floore (an archeologist on behalf of the Institute for Pre-and Proto History of the University of Amsterdam) and Ab Hoving (on behalf of the Rijksmuseum) traveled to Moscow in an attempt to determine whether this “wooden construction” was indeed part of the ship of Barentsz.

In Ab’s words: Viewing this 4m x 1m section of the WB’s construction and its significance in world maritime history is hard to describe. Of all expedition ships which ever sailed the oceans, not a single piece has ever been found (obviously the book was published well before the discovery of the Endurance) – not of Columbus’s Santa Maria, nor of Cook’s Endeavour, let alone the ships of Vasco da Gama and Magellan.

View attachment 322170

A drawing of the discovered hull portion by the Boyarsky Group.

So, what can we learn from the hull portion of the WB that was found? The single most significant aspect is that the planking consisted of a double layer. It is important that we distinguish here between what the Dutch called a “Dubbeling” (Doubling) and a “Dubbele Huidlaag” (Double Layer of Planking).

"Dubbeling (Doubling)

“Dubbeling” (Doubling) was an extra layer of wood (normally consisting of fir- or firewood) of approximately 1 cm in thickness which was nailed on the outside of the hull below the waterline to prevent the hull from being infested or affected by “paalworm/shipworm” (Teredo Navalis). The flat and square-headed nails of which four were nailed into a square-inch of planking would rust to one another to form an impenetrable layer of corrosion around the ship. It was very seldom that the paalworm managed to penetrate this layer of corrosion*. In case the worms did manage to penetrate the corrosive layer, they would encounter a further layer of cows’ hair and tar which was smeared between the two layers of planking. Should the worms manage to penetrate that layer as well, they could well cause the total destruction of the ship. The “dubbeling” was replaced after each long or major trip.

View attachment 322171

A piece of shipworm-infested timber.

*This was in fact the first iteration of what became common practice in the 18th Century – the coppering of hulls.

It is interesting to note that a particularly dangerous variant of the paalworm lived in the hot areas such as the tropics and therefore it is no wonder that “dubbeling” was found on almost all of the shipwrecks that have been discovered in these areas. However, ships sailing to and around the Scandinavian countries did not need “doubling” as the very cold and harsh water of the Oostzee was completely devoid of shipworm.

DOUBLE-LAYERED PLANKING

A Double layer of planking, however, was according to Ab, an altogether different story and is a concept which is not yet fully understood. This was something that was found almost exclusively on Dutch ships around the year 1600.

It is important to note that the discovered hull portion of the Willem Barentsz is not the only proof of the double layer at the time. In “bestekken” (specification lists) of the time it is expressly mentioned. The wreck of the Scheurrak SO1 (previously mentioned in my log on quite a number of occasions) had a 4-inch layer of outer planking attached to the 4-inch layer of inner planking and the hull frames by means of wooden trennels. The wreck of the Mauritius which has been lying off the coast of Gabon since 1609, not only featured double planking as well, but also had a layer of lead between the two planking layers. The outer planking layer, however, was not secured to the hull frames, but only to the first planking layer by iron nails; not trennels. In addition to all of this, the Mauritius also featured “dubbeling” (doubling of the hull below the waterline as safeguard against the paalworm.

View attachment 322189

This is a drawing of the layout of the double-layered planking found on the wreck of the Mauritius - a Dutch ship which stranded off the coast of Gabon in 1609.

On the Willem Barentsz, both layers of planking were only 4cm (1.5-inches) in thickness and were secured to each other by nails – just like on the Mauritius. Which begs the following question: What was the purpose of the double layer of planking?

To be honest, there is no consensus or clear-cut answer.

Did any of the above three rationales play in a role in the double planking of the WB? Ab Hoving reckons there are two more possibilities to consider:

- There are those who believe that it was done to reduce the chances of leakage – a fact which was borne out after examination of the Batavia wreck. There planks showed what seemed to have been an overlap of seams by the two different layers of planking.

- Others point to the era in which these ships were built – a time of transition from clinker- to carvel planking. With the latter, only the planks’ edges served as the contact area between planks – other than that, there was no additional contact surface between individual planks. Hull strength was achieved by two possible means: (a) A double layer of planking; or (b) thicker hull frames. Even though both options were initially tried, the eventual choice fell on the thicker hull frames

- A third group believes it has to do with the type of ship that was built. As trade became increasingly important, ships grew exponentially in size. Clinker planking, for instance, limited the length of the ships that could be built whereas carvel planking allowed ships of greater length to be built. However, as the ships grew longer, it placed severe stress on the lengthwise strength of planks. A logical solution would have been to adopt a double layer of planking to increase strength.

In conclusion, Ab makes the following observations:

- Sometimes, double planking could provide a ship with greater stability by making the hull somewhat wider – in English this is called a girdled ship. In such a case though, the girdle was never wider than one meter and was applied at waterline-height. This was not the case with the WB.

- Another reason could be the fact that the ship was destined for a polar expedition so a double hull would provide additional strength and provide protection against pack ice. This is specifically mentioned in the specification list of the Zeeland ship, De Zwane, as she was prepared for the 1595 trip.

The thickness of the first layer of planking was much too thin for a ship’s length of 67.5 feet while the double layer was way too thick for a ship of the same length. If the double layer was intended as a means of strengthening the hull, why was it only nailed to the first layer and not secured to the frames as well? And why were nails used when trennels were stronger? In fact, the discovery of the hull portion seems to raise more questions rather than answer any.

TEREDO NAVALIS / SHIPWORM

There’s something interesting about Shipworms. They are not a worm but a saltwater clam. Shipworms get their name from their long, narrow, cylindrical bodies but the worm resemblance ends there. A closer look at the creature reveals a shell at its front. This shell has 2 halves with a gap in between like a clam shell. In the gap pokes a muscular foot that acts like a suction cup, holding the shell in place while its razor-sharp edges scrape the wood ahead of it. At the top, 2 flesh-toned siphons swish water over massive gills. At the bottom, a slimy, eyeless head resembles a mix of wet lips & diseased intestines. In between, a glistening gunpowder-blue body stretches up to 4 feet long.

View attachment 322192

View attachment 322193

Instead of eating, bacteria in the creature’s gills helps it suck energy from sulfur. The whole thing is sheathed in a curving tusk-like tube created from the Shipworm’s excretion of calcium carbonate. Shipworms eat sawdust and its stomach has a pouch for storing sawdust and a special gland for digesting wood particles. These “termites of the sea” also have an organ full of bacteria that digest wood. The bacteria take nitrogen from the water and convert it to protein for the worm, since wood doesn’t supply protein. The bacteria in return, get nutrients from their host. A Shipworm begins life like most marine invertebrates, as a tiny piece of meat in the plankton soup of the sea.

Cheers,

Stephen.

- Joined

- Jan 9, 2020

- Messages

- 10,566

- Points

- 938

It's only a pleasure, Stephen. I am glad that you found it interesting.Well Heinrich that was very interesting and educational, thanks for posting it.

Cheers,

Stephen.

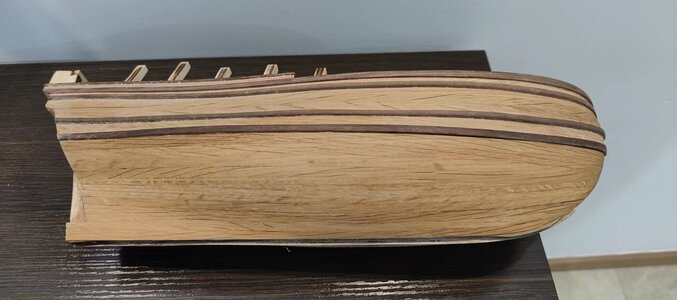

Good Morning Heinrich. I know you seek perfection and this is pretty darn close. The spiling strake is hardly noticeable. For once I am using my laptop and not my phone and even with the zoom function it all looks fantastic. What are you thoughts with regards to oiling the hull? Cheers GrantEnough is enough ...

View attachment 322359

View attachment 322360

View attachment 322361

Single-Layer Oak.

- Joined

- Jan 9, 2020

- Messages

- 10,566

- Points

- 938

Thank you very much Grant! My luck - I take Macro shots and then you go and zoom in!Good Morning Heinrich. I know you seek perfection and this is pretty darn close. The spiling strake is hardly noticeable. For once I am using my laptop and not my phone and even with the zoom function it all looks fantastic. What are you thoughts with regards to oiling the hull? Cheers Grant

If the spiling line shows, it's not good enough, so more sanding tonight.

If the spiling line shows, it's not good enough, so more sanding tonight.

From the point of historical accuracy, the hull needs to be painted below the waterline as per Ab's model. Keeping this in mind, I could have taken many shortcuts with the hull planking below the waterline, but that's just not me. As to the oak above the waterline, I have a few options. I can use the Clou stain that Hans sent me, my Tung Oil, shellac as a finishing layer or a polyurethane varnish. I will still decide on that later on - first I have a Port Side of which I need to finish the planking.

Heinrich my friend, my last visit here was friday afternoon, and you learned me two things this morning.

The first one : Check the build of Heinrich more, don't do it after two and a halve days.

The second one : what a nasty buggers they are for wooden ships, i would't like to have a live worm in my hands, that almost looks like an Anaconda baby.

Next point, your Willem Barentsz looks excellent now you closed one side of the hull, congrats, and a very deep bend from me.

For now, have fun with the other side of the hull

The first one : Check the build of Heinrich more, don't do it after two and a halve days.

The second one : what a nasty buggers they are for wooden ships, i would't like to have a live worm in my hands, that almost looks like an Anaconda baby.

Next point, your Willem Barentsz looks excellent now you closed one side of the hull, congrats, and a very deep bend from me.

For now, have fun with the other side of the hull

- Joined

- Jan 9, 2020

- Messages

- 10,566

- Points

- 938

You are right my friend. Those paalworm are terrible things and they grow up to 4 feet long. Thank you for the kind words on the hull. For the rest of the day i am taking a break and tomorrow I will continue. I also have a visitor I have to look after for the next two days!Heinrich my friend, my last visit here was friday afternoon, and you learned me two things this morning.

The first one : Check the build of Heinrich more, don't do it after two and a halve days.

The second one : what a nasty buggers they are for wooden ships, i would't like to have a live worm in my hands, that almost looks like an Anaconda baby.

Next point, your Willem Barentsz looks excellent now you closed one side of the hull, congrats, and a very deep bend from me.

For now, have fun with the other side of the hull

You are right my friend. Those paalworm are terrible things and they grow up to 4 feet long. Thank you for the kind words on the hull. For the rest of the day i am taking a break and tomorrow I will continue. I also have a visitor I have to look after for the next two days!

That looks like a nice and cute dog Heinrich, what is his/her name??