- Joined

- Jun 4, 2024

- Messages

- 66

- Points

- 68

Hi Kurt;

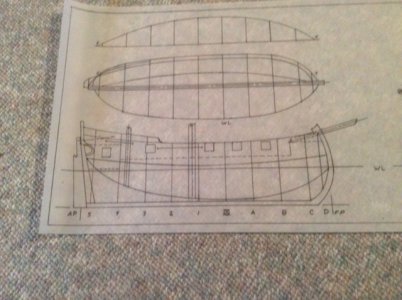

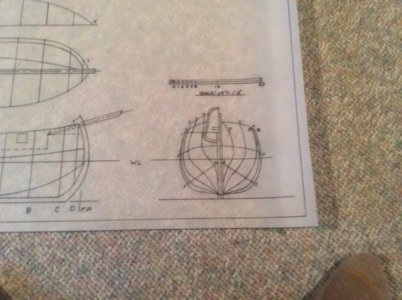

Buttock lines are vertical; water lines are parallel to a horizontal, either the keel or the waterline. Each can only be used to plot a series of points on a single plane.

The rising and narrowing lines allow the plotting of a series of points in three-dimensional space, so in a way one could say that they are a combination of buttock and water lines. However, the rising and narrowing lines are created without reference to either waterlines or buttock lines, and are a completely separate entity. As they were normally (not always) segments of curves, the points where each line crossed a frame timber could be calculated mathematically. This enabled accurate plotting at full size, rather than scaling from a draught.

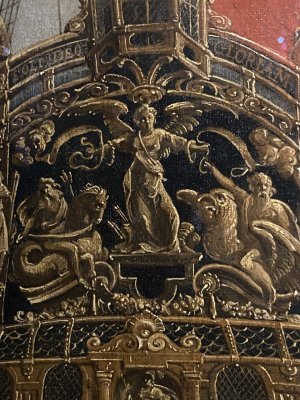

It has been suggested that Matthew Baker was responsible for introducing this system, but the truth of this is unlikely to ever be known.

Ratty

Buttock lines are vertical; water lines are parallel to a horizontal, either the keel or the waterline. Each can only be used to plot a series of points on a single plane.

The rising and narrowing lines allow the plotting of a series of points in three-dimensional space, so in a way one could say that they are a combination of buttock and water lines. However, the rising and narrowing lines are created without reference to either waterlines or buttock lines, and are a completely separate entity. As they were normally (not always) segments of curves, the points where each line crossed a frame timber could be calculated mathematically. This enabled accurate plotting at full size, rather than scaling from a draught.

It has been suggested that Matthew Baker was responsible for introducing this system, but the truth of this is unlikely to ever be known.

Ratty