@dockattner

@AllanKP69

@serikoff

@Peter Voogt

@Mirek

Hello colleagues,

It's always great to receive feedback. It's very motivating and makes me very happy. Thank you so much for that, and also thank you to everyone else for the many likes.

Even though the La Créole is by no means my first ship model, I've been working on its rigging for quite some time now—and yet it still feels like I'm venturing into uncharted territory.

For the first time, I'm attempting to recreate the entire rigging almost completely and with historical accuracy. My basis for this isn't just Boudriot's monograph on the La Créole. I'm also drawing on primary sources, available specialist literature, and everything the internet has to offer in terms of reliable information.

In addition, there are the tips, discussions, and suggestions from the forum, which constantly open up new perspectives. Often, the various sources lead to slightly different solutions, and in the end, the task remains to decide on a plausible, logically sound option. The more I delve into each individual piece of rope, the more I marvel at this ingenious interplay of the rigging—a finely tuned system in which each element absorbs, transmits, and balances forces.

And that, for me, is precisely the special charm of model making: the learning, the discovering, the understanding—and, of course, the joy of every successful detail. Added to that is the quiet hope of one day seeing this model finished and standing before me.

And so it continues…

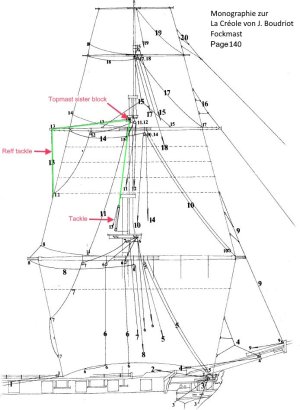

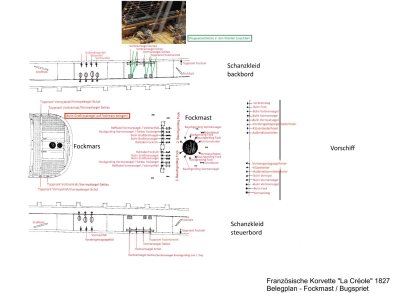

Attaching the Fore Topsail Yard - Vergue de hune de misaine

Now that the fore yard has been rigged, we'll proceed with attaching the fore topsail yard, working systematically from the bottom up. For this, it's necessary to install the corresponding fore topsail tye.

The tye's components - including the topsail halyard spacers (gouvernail de drisse) and tackle - were manufactured and documented some time ago; the blocks are also already in place on the model.

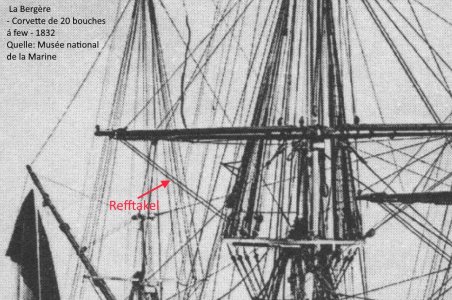

During the preparation, the question arose as to the correct tarring or coloring of the tye with halyard. A recent close-up photograph of the Hermione replica shows the the rope of the tye just before the tackle block, in direct comparison to the backstay that guides the topsail halyard.

View attachment 577265

Source: Association Hermione – La Fayette, “Dico de l’Hermione”, December 9, Itague.

The image clearly shows that the topsail tye is visibly lighter in color and therefore only lightly tarred, if at all, in contrast to the heavily tarred backstay. This likely corresponds to historical practice. The fore topsail tye is part of the running rigging.

View attachment 577264

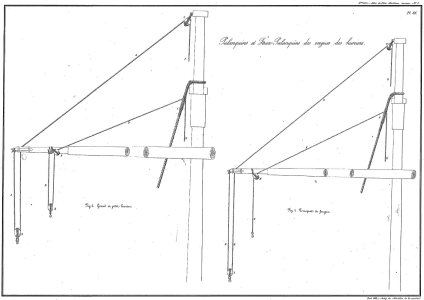

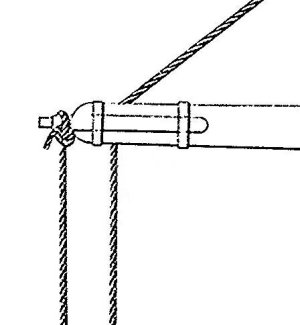

The tye in general (fore topsail yard ø 37 mm) was served in the sections where it passed through the blocks (according to F. A. Coste 1827). Therefore, to prepare for the fore topsail tye, this area had to be defined on the model. Appropriate markings were made on a temporarily installed section of rope. At each end of the tye, there was a spliced eye for attaching the halyard blocks. These sections also received appropriate serving, as can be seen in the following pictures.

I prepared the lashings for the halyard spacers in the form of rings made from thin silk yarn. I was then able to stiffen these rings with diluted white glue and pull them onto the rope, sliding them over the spacer at the appropriate points.

View attachment 577266

One side of the topsail tye with halyard could be made completely, and therefore conveniently, outside the model.

Only after the rope is threaded through the blocks can the other side (with the serving already prepared, and silk thread for the remaining serving) be finished on the model, albeit somewhat less conveniently.

Attaching the halyard spacers requires opening the seizings of the fore topsail backstays. Unfortunately, I didn't consider that something would be added there when rigging the standing rigging.

View attachment 577270

The following pictures show the fore topsail tye already installed in the block of the middle of the fore topsail yard.

View attachment 577267

View attachment 577268

View attachment 577269

The last picture shows both tye blocks under the braiding of the shrouds with the already pulled-in tye rope.

View attachment 577271

In the next step, I will then complete the starboard side of the tye with halyard.

To be continued...