-

Win a Free Custom Engraved Brass Coin!!!

As a way to introduce our brass coins to the community, we will raffle off a free coin during the month of August. Follow link ABOVE for instructions for entering.

-

PRE-ORDER SHIPS IN SCALE TODAY!

The beloved Ships in Scale Magazine is back and charting a new course for 2026!

Discover new skills, new techniques, and new inspirations in every issue.

NOTE THAT OUR FIRST ISSUE WILL BE JAN/FEB 2026

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Mary Rose

- Thread starter Graham

- Start date

- Watchers 54

-

- Tags

- caldercraft mary rose

- Joined

- Nov 25, 2018

- Messages

- 635

- Points

- 403

Historians like to argue over the word "revolution", especially when it concerns military or naval issues. Any dramatic or large-scale change in the status quo occurs over a period of time, from the" military revolution "of the late Renaissance to the" naval revolution " of the mid-19th century. However, in a few periods of history, these terms were used as often as in the Tudor era. Their rule spans a century that has witnessed profound religious, economic, social, cultural, political, and military changes.

Like other technological fields, the art of shipbuilding and the science of weapons, this period of time has undergone major changes, and the increasing number of artillery pieces installed on ships, had a strong influence on the design of naval vessels. Few of the reigning monarchs of the time knew as much about the power of naval artillery as king Henry VIII of England (reigned 1509-47). While his father, Henry VII (reigned 1485-1509), simply encouraged the placement of guns on ships, the young Henry ordered the initial design of Royal warships, specifically for the installation of heavy guns. This process of combining artillery and warships together, and designing ships as gun platforms, reached its apogee during the reign of his daughter Elizabeth I (ruled 1558-1603).

Henry VII Tudor (28 January 1457-21 April 1509) was king of England and sovereign of Ireland (1485-1509), the first monarch of the Tudor dynasty.

Henry VIII Tudor (28 June 1491-28 January 1547) was king of England from 22 April 1509, the son and heir of king Henry VII of England, the second English monarch of the Tudor dynasty.

Elizabeth I Tudor (7 September 1533 — 24 March 1603), Good Queen Bess, virgin Queen of England and Queen of Ireland from 17 November 1558, the last of the Tudor dynasty. The youngest daughter of king Henry VIII of England and his second wife Anne Boleyn.

From the time of Henry VII (Henry Tudor), the old York dynasty fleet he inherited in 1485 until the death of Henry VIII's son, Edward VI in 1553, completely changed its essence - from late Medieval ships designed to transport land forces to the battle site, to specially designed as gun platforms for the fleet under the leadership of Henry VIII. For ease of understanding, we can divide this development into three distinct distinct phases: the warships of the late middle Ages, the karakki, and the perestroika period.

Part of the painting "the Departure of Henry VIII to France", drawn by an unknown artist, depicts the events of 1520, when Henry VIII met with Francis I on the "Field of Golden brocade". The four-masted vessel in the background probably represents the "Henry grace e'due", although the warship's displacement of 1,000 tons meant that it could not enter Dover Harbor - the place that is depicted in the picture.

Warships of the late middle Ages

Before we consider the development of warships during the reign of the Tudor kings, it is necessary to take a fleeting look at the changing face of the European ship during the 15th century. At that time, there were two traditions of shipbuilding – Northern European and Mediterranean. In the 15th century, the growth of Maritime trade led to the borrowing of ideas from each other between these two traditions, thus creating a new style of shipbuilding that incorporated the best elements of each school. By 1485, the unification of these traditions was in full swing, and the process accelerated further in the early 16th century.

English warship, XIV century-Hundred years ' war

The Northern shipbuilding tradition had already created the cogg, a workhorse on Northern European shipping lines in the 14th century. It was also a type of ship that could be used for military purposes, so merchant coggies were widely used in the service as warships. The roots of the cogg design go back to Knorr, used by 8th-century Scandinavian merchants. Both vessels had the same form of construction, straight sails, still inherited from their ancestor-the nave, a type of vessel that served as a link between the early and late designs of the ship. The typical cogg, was a squat, broad ship, with a rounded bow and stern, and often with well-defined fore and aft superstructures. Usually carried a single mast in the middle of the ship's hull, although some illustrations from the 14th and 15th centuries show ships with a small mizzen mast.

Cogg

The cogg gave way to a new type of vessel, an enlarged version of the cogg, sometimes called the Hulk (a type of vessel known in Spain and Portugal as the nao). This was due to the mutual influence of Northern and southern European shipbuilding traditions. On Mediterranean ships, the technique of "karavel" hull plating (vglad) was used, when the hull plating boards rest against each other, and do not overlap. By the 14th century, both schools began to adopt each other's construction techniques, as shown by the introduction of "Caravel" sheathing in France and the Iberian Peninsula, and the use of the rudder on the achterstev (as on the cog) on ships in the Mediterranean. The Hulk combined the best elements of both traditions, allowing ships to be built with a larger hull than on previous clinker vessels, and using a combination of Northern and southern European sailing equipment and steering systems, making the ship's handling more efficient than on earlier vessels. In 16th-century England, the term "Hulk" was used to describe Northern European but not English merchant ships, while by the end of the century, the term had taken hold of worn – out (and usually large) vessels-a term that is still used today.

In the second half of the 15th century, the Hanseatic cohg was further developed. Two-masted claws appeared, and later three-masted ones. Their displacement was 300-550 tons. For protection from attacks by pirates and enemy ships, the Hansa had crossbowmen and several bombards on merchant ships. Since the beginning of the XVI century, in addition to trade, military claws were built, which escorted merchant ships on the sea crossing. They were equipped with 20 or more bombards laid on wooden carriages. The length of the military cog was 28 m, width 8 m, draft 2.8 m, and displacement 500 tons or more. At the stern and bow of both merchant and military coggs, there were still highly developed superstructures. The foremast and mainmast, slightly inclined to the bow, carried a single-square sail, and the mizzen carried a slanting sail. On the Mediterranean sea, two-masted claws with slanting sails were sometimes encountered.

Karakka

We do not know exactly when the first caracca appeared, but as early as 1304, the Florentine chronicler Giovanni Villani claimed that Italian shipbuilders copied the design of the buck cogg when building the ship referred to as the Koch. Only a few fine pictorial records survive of the early Koch, but by 1340 the largest of them, was known as the baronial Koch, which was larger, with a hull with a deeper draft than the original Basque Koch. It almost certainly had two masts, carrying a combination of sail rigging consisting of straight sails on the mainmast and a lateen sail on the mizzen mast. By the end of the 14th century, the term "caracca" was used by the English to describe Genoese merchant ships of this type, although there is no clear evidence that they sailed as far North as the British Isles. In the Iberian Peninsula, the same vessel was known as the nao, although the term was also used in reference to the Spanish version of the Northern European Hulk. In fact, throughout the 15th century, the early caracchi, nao, and Hulk all belonged to similar General ship types.

Although there is evidence that the two-masted Kochi sailed the Mediterranean at the end of the 14th century, their first detailed mention in English written sources is noted in 1410, when the two-masted Genoese caracca was captured by English pirates, and the English crown claimed ownership of this ship. On the other, like the Carrack, there is mention in the official documents for next year. By 1417, Henry V (reigned 1413-22) had purchased 8 Genoese caraccas, which became part of his nascent Royal Navy. Six of them were described by contemporaries as vessels with a displacement of 500 tons, equipped with two masts-the mainmast and the" Mesan " - mizzen. In the last years of Henry's reign, English shipbuilders added two-masted ships to his fleet, thus confirming that the design of the cochia was copied by English Royal shipbuilders. However, by the end of Henry's reign, these same shipbuilders had taken one step forward.

A year after his victory over the French at the battle of Agincourt (1415), Henry V ordered the construction of two new warships, one at Bayonne on the coast of Aquitaine, and the other at Southampton in Hampshire. The Southampton ship was larger than the ship built at Bayonne, and when it was launched in 1418, it was noted that it had a displacement of 1,400 tons. Little is known about this huge ship, called Grace Dieu ("grace Dieu"), there are several records of the inventory of its stocks, conducted after it was put into conservation in 1420. Its wreckage was discovered near Barsledon on the river humble, and at various times since the mid-19th century it has been examined and samples taken from it. An examination of the wreckage showed that her hull had a clinker skin (vnakroy), a keel about 125 feet long and 50 feet wide. In size, this ship was larger than any other ship built in the British Isles before the 17th century. The captain of the Florentine galley was an eye-witness who saw the grace Dew, and left evidence that the ship was about 184 feet long at deck level, with a mainmast 200 feet high and 22 feet in circumference.

Like other technological fields, the art of shipbuilding and the science of weapons, this period of time has undergone major changes, and the increasing number of artillery pieces installed on ships, had a strong influence on the design of naval vessels. Few of the reigning monarchs of the time knew as much about the power of naval artillery as king Henry VIII of England (reigned 1509-47). While his father, Henry VII (reigned 1485-1509), simply encouraged the placement of guns on ships, the young Henry ordered the initial design of Royal warships, specifically for the installation of heavy guns. This process of combining artillery and warships together, and designing ships as gun platforms, reached its apogee during the reign of his daughter Elizabeth I (ruled 1558-1603).

Henry VII Tudor (28 January 1457-21 April 1509) was king of England and sovereign of Ireland (1485-1509), the first monarch of the Tudor dynasty.

Henry VIII Tudor (28 June 1491-28 January 1547) was king of England from 22 April 1509, the son and heir of king Henry VII of England, the second English monarch of the Tudor dynasty.

Elizabeth I Tudor (7 September 1533 — 24 March 1603), Good Queen Bess, virgin Queen of England and Queen of Ireland from 17 November 1558, the last of the Tudor dynasty. The youngest daughter of king Henry VIII of England and his second wife Anne Boleyn.

From the time of Henry VII (Henry Tudor), the old York dynasty fleet he inherited in 1485 until the death of Henry VIII's son, Edward VI in 1553, completely changed its essence - from late Medieval ships designed to transport land forces to the battle site, to specially designed as gun platforms for the fleet under the leadership of Henry VIII. For ease of understanding, we can divide this development into three distinct distinct phases: the warships of the late middle Ages, the karakki, and the perestroika period.

Part of the painting "the Departure of Henry VIII to France", drawn by an unknown artist, depicts the events of 1520, when Henry VIII met with Francis I on the "Field of Golden brocade". The four-masted vessel in the background probably represents the "Henry grace e'due", although the warship's displacement of 1,000 tons meant that it could not enter Dover Harbor - the place that is depicted in the picture.

Warships of the late middle Ages

Before we consider the development of warships during the reign of the Tudor kings, it is necessary to take a fleeting look at the changing face of the European ship during the 15th century. At that time, there were two traditions of shipbuilding – Northern European and Mediterranean. In the 15th century, the growth of Maritime trade led to the borrowing of ideas from each other between these two traditions, thus creating a new style of shipbuilding that incorporated the best elements of each school. By 1485, the unification of these traditions was in full swing, and the process accelerated further in the early 16th century.

English warship, XIV century-Hundred years ' war

The Northern shipbuilding tradition had already created the cogg, a workhorse on Northern European shipping lines in the 14th century. It was also a type of ship that could be used for military purposes, so merchant coggies were widely used in the service as warships. The roots of the cogg design go back to Knorr, used by 8th-century Scandinavian merchants. Both vessels had the same form of construction, straight sails, still inherited from their ancestor-the nave, a type of vessel that served as a link between the early and late designs of the ship. The typical cogg, was a squat, broad ship, with a rounded bow and stern, and often with well-defined fore and aft superstructures. Usually carried a single mast in the middle of the ship's hull, although some illustrations from the 14th and 15th centuries show ships with a small mizzen mast.

Cogg

The cogg gave way to a new type of vessel, an enlarged version of the cogg, sometimes called the Hulk (a type of vessel known in Spain and Portugal as the nao). This was due to the mutual influence of Northern and southern European shipbuilding traditions. On Mediterranean ships, the technique of "karavel" hull plating (vglad) was used, when the hull plating boards rest against each other, and do not overlap. By the 14th century, both schools began to adopt each other's construction techniques, as shown by the introduction of "Caravel" sheathing in France and the Iberian Peninsula, and the use of the rudder on the achterstev (as on the cog) on ships in the Mediterranean. The Hulk combined the best elements of both traditions, allowing ships to be built with a larger hull than on previous clinker vessels, and using a combination of Northern and southern European sailing equipment and steering systems, making the ship's handling more efficient than on earlier vessels. In 16th-century England, the term "Hulk" was used to describe Northern European but not English merchant ships, while by the end of the century, the term had taken hold of worn – out (and usually large) vessels-a term that is still used today.

In the second half of the 15th century, the Hanseatic cohg was further developed. Two-masted claws appeared, and later three-masted ones. Their displacement was 300-550 tons. For protection from attacks by pirates and enemy ships, the Hansa had crossbowmen and several bombards on merchant ships. Since the beginning of the XVI century, in addition to trade, military claws were built, which escorted merchant ships on the sea crossing. They were equipped with 20 or more bombards laid on wooden carriages. The length of the military cog was 28 m, width 8 m, draft 2.8 m, and displacement 500 tons or more. At the stern and bow of both merchant and military coggs, there were still highly developed superstructures. The foremast and mainmast, slightly inclined to the bow, carried a single-square sail, and the mizzen carried a slanting sail. On the Mediterranean sea, two-masted claws with slanting sails were sometimes encountered.

Karakka

We do not know exactly when the first caracca appeared, but as early as 1304, the Florentine chronicler Giovanni Villani claimed that Italian shipbuilders copied the design of the buck cogg when building the ship referred to as the Koch. Only a few fine pictorial records survive of the early Koch, but by 1340 the largest of them, was known as the baronial Koch, which was larger, with a hull with a deeper draft than the original Basque Koch. It almost certainly had two masts, carrying a combination of sail rigging consisting of straight sails on the mainmast and a lateen sail on the mizzen mast. By the end of the 14th century, the term "caracca" was used by the English to describe Genoese merchant ships of this type, although there is no clear evidence that they sailed as far North as the British Isles. In the Iberian Peninsula, the same vessel was known as the nao, although the term was also used in reference to the Spanish version of the Northern European Hulk. In fact, throughout the 15th century, the early caracchi, nao, and Hulk all belonged to similar General ship types.

Although there is evidence that the two-masted Kochi sailed the Mediterranean at the end of the 14th century, their first detailed mention in English written sources is noted in 1410, when the two-masted Genoese caracca was captured by English pirates, and the English crown claimed ownership of this ship. On the other, like the Carrack, there is mention in the official documents for next year. By 1417, Henry V (reigned 1413-22) had purchased 8 Genoese caraccas, which became part of his nascent Royal Navy. Six of them were described by contemporaries as vessels with a displacement of 500 tons, equipped with two masts-the mainmast and the" Mesan " - mizzen. In the last years of Henry's reign, English shipbuilders added two-masted ships to his fleet, thus confirming that the design of the cochia was copied by English Royal shipbuilders. However, by the end of Henry's reign, these same shipbuilders had taken one step forward.

A year after his victory over the French at the battle of Agincourt (1415), Henry V ordered the construction of two new warships, one at Bayonne on the coast of Aquitaine, and the other at Southampton in Hampshire. The Southampton ship was larger than the ship built at Bayonne, and when it was launched in 1418, it was noted that it had a displacement of 1,400 tons. Little is known about this huge ship, called Grace Dieu ("grace Dieu"), there are several records of the inventory of its stocks, conducted after it was put into conservation in 1420. Its wreckage was discovered near Barsledon on the river humble, and at various times since the mid-19th century it has been examined and samples taken from it. An examination of the wreckage showed that her hull had a clinker skin (vnakroy), a keel about 125 feet long and 50 feet wide. In size, this ship was larger than any other ship built in the British Isles before the 17th century. The captain of the Florentine galley was an eye-witness who saw the grace Dew, and left evidence that the ship was about 184 feet long at deck level, with a mainmast 200 feet high and 22 feet in circumference.

- Joined

- Nov 25, 2018

- Messages

- 635

- Points

- 403

Type: the "Great ship" (a Carrack), nicknamed "great Harry". Built in 1514 at Woolwich

Displacement: 1000 tons

Keel length: about 130 feet (39 m)

Deck width: about 50 feet (15 m)

Armament: 80 guns (51 heavy, the rest swivel guns; in the inventory list of weapons on Board a total of 112 guns, including hand firearms

Crew (1536): 700 men (including 400 soldiers and 40 gunners)

One of the most ambitious warships built during the Tudor dynasty, its construction is probably a direct response to the construction of the ship Great Michael ("great Michael") by the king of Scotland – James IV. Unfortunately, it took three decades before the ship was able to open fire with its guns, most of the time it spent on conservation. The ship was built more for prestige than for any military value, and in 1520 she accompanied Henry VIII from Dover to Calais to meet Francis I on the " Field of Golden brocade»:

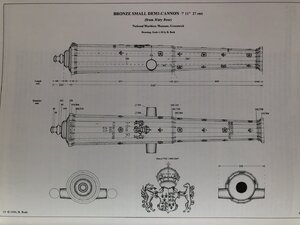

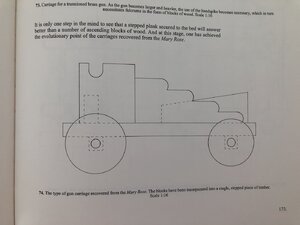

Even then, the ship's displacement prevented it from leaving or entering the Harbor. While its appearance was impressive, the cost of operating it in peacetime was considered prohibitive, and it came to be regarded as a kind of "white elephant". The drawing shows one of the forged iron breech-loading guns that the ship was armed with, mounted on a carriage.

Another notable feature of the 15th-century North European karakka was the shape of its stern. The hull skin (or belt of the ship's outer skin) curved at the top of the stern, forming a more rounded stern of the ship than on ships of later construction. This feature can be seen on the Hulk of the time. From 1488 and later, this practice ceased to simplify the construction of the ship, when the skin belt was attached to the aft frames of the ship, and a transom (flat) stern was added. This simplification became important when it was necessary to build heavy ships capable of withstanding heavy artillery fire.

to be continued...

Displacement: 1000 tons

Keel length: about 130 feet (39 m)

Deck width: about 50 feet (15 m)

Armament: 80 guns (51 heavy, the rest swivel guns; in the inventory list of weapons on Board a total of 112 guns, including hand firearms

Crew (1536): 700 men (including 400 soldiers and 40 gunners)

One of the most ambitious warships built during the Tudor dynasty, its construction is probably a direct response to the construction of the ship Great Michael ("great Michael") by the king of Scotland – James IV. Unfortunately, it took three decades before the ship was able to open fire with its guns, most of the time it spent on conservation. The ship was built more for prestige than for any military value, and in 1520 she accompanied Henry VIII from Dover to Calais to meet Francis I on the " Field of Golden brocade»:

Even then, the ship's displacement prevented it from leaving or entering the Harbor. While its appearance was impressive, the cost of operating it in peacetime was considered prohibitive, and it came to be regarded as a kind of "white elephant". The drawing shows one of the forged iron breech-loading guns that the ship was armed with, mounted on a carriage.

Another notable feature of the 15th-century North European karakka was the shape of its stern. The hull skin (or belt of the ship's outer skin) curved at the top of the stern, forming a more rounded stern of the ship than on ships of later construction. This feature can be seen on the Hulk of the time. From 1488 and later, this practice ceased to simplify the construction of the ship, when the skin belt was attached to the aft frames of the ship, and a transom (flat) stern was added. This simplification became important when it was necessary to build heavy ships capable of withstanding heavy artillery fire.

to be continued...

- Joined

- Nov 25, 2018

- Messages

- 635

- Points

- 403

Perestroika period

The Royal Navy inherited by the first Tudor monarch, Henry VII, essentially consisted of their karakk. All but one of his eight ships were of this type, with the exception of the ship named Nicholas of London-which was sold by the end of the first year of his reign. Also at this time was sold two karakki. Although we don't know much about their actual size, financial records state that all the remaining five ships were large, all former merchant ships with high fore and aft superstructures. All five carried mixed artillery from "port guns" (forged iron, breech-loading guns) and small swivel guns. These weapons of a later period were also breech-loading and usually made of forged iron, but at the same time, swivel guns were small enough to be mounted on a swivel (or rotating support) on the ship's side – a device vaguely similar to a modern machine gun.

Artistic reconstruction (Monleon, 1892)of the quarterdeck of the Columbian Santa Maria. Such primitive gun emplacements probably existed before the end of the XVI century

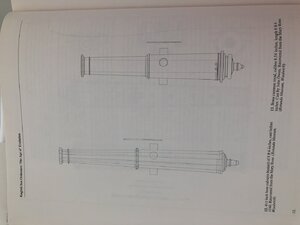

"Port piece" or long-barreled fogler, typical of the 2nd half of the XV-1st half of the XVI centuries, on the machine - "deck", raised from the sunken in the XVI century "Mary rose"; drawing, apparently, of the XIX century. Similar ship machines were used on ships of different countries and also had a pair of solid wooden wheels of small diameter on the axis placed under the front, "beveled" part of the machine

One of these carracks, the Mary of Tower, in 1485 carried no less than 58 guns, most of which were either portable or swivel guns. Portable guns ranged in size from small hand-held guns, to large-caliber firearms (known as arquebuses), similar to modern bazookas, and equipped with bipods that could rest against the side of the ship to reduce recoil when fired. The second ship, Grace Dieu, acquired in 1473, was listed as carrying 21 guns of the same type. Drawings such as" Warwick skating "or the Flemish print" Kraek " (as the caracca is called in Flemish) show that swivel guns could be mounted either on the waist or on superstructures, from where they could fire over the side. This arrangement of guns was possible because the guns were light enough and their weight did not affect the stability of the ship. Obviously, mounting heavy guns in the same way made the ship unstable until a way was found to mount the guns closer to the waterline. There was already a way to achieve this. The "Kraek" engraving, which dates back to about 1468, shows a large armed merchant ship with loading ports carved at the bottom of the hull, below the aft superstructure. The Warwick scroll also includes an image of a caracca sailing under the flag of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick (1428-71), armed with five or six "port" guns.

"Regent" and "Maria La Cordillera". Battle of Brest, 1512

The largest ship of the Tudor Navy before the Henry grace e'due, the four-masted Regent was a floating symbol of Tudor power, richly decorated and armed with no less than 225 guns, although almost all of them were either swivel guns or hand-held firearms. By the time Sir Thomas Nivet sailed on it and engaged the French on August 10, 1512, off Brest, the ship boasted an additional battery of heavy guns.

During the battle, the mighty ship Maria La Cordillera separated from the rest of the French fleet and was surrounded by English ships. Captain Gervais de Porzmoger, repulsed all attempts to Board his ship until, in the end, the "Regent" failed to catch on the side of the French warship. During the battle, a fire broke out on the Maria La Cordillera, and the flames quickly spread to the Regent. Soon both ships were engulfed in flames,and sank with a huge number of lives. The picture shows the moment when both ships grappled and started fighting.

Characteristics of the ship "Regent"

Type: the "Great ship" (a Carrack), originally known as the "grace Dieu". Built in 1488

Displacement: 1000 tons

Keel length: about 140 feet (42 m)

Deck width: about 45 feet ( 13.5 m)

Armament: 180 guns (mainly swivel guns and hand-held firearms)

The crew (1512): 800 people (including over 450 soldiers and 50 gunners)

Participated in the battle of Brest in 1512, and was lost in battle

The warship Sovereign, 1512

Type: "Great ship" (karakka), originally called Trinity Sovereign ("Trinity Sovereign").Built in 1488.

Displacement: 800 tons

Keel length: about 125 feet (37.5 m)

Deck width: about 40 feet (12 m)

Armament: 100 guns (most of them swivel guns and hand firearms) - 69 guns in 1509

Crew (1513): 700 men (including 400 soldiers and 40 gunners) Service notes: Rebuilt in 1509.

Participated in the naval battle of Brest in 1512.

Declared unfit for navigation in 1521 and excluded from the Navy

Warship great Bark II, 1547

Type: Galeass, originally called Great Galley "great gally". Built in 1515 in Greenwich. Sometimes known as Great Galleass "great Galleass", from 1642 it was known as Great Bark "great Bark" or Great Galleon " great Galleon"

Displacement: 800 tons

Keel length: about 100 feet (30 m)

Deck width: about 25 feet (

Armament: 87 guns (23 heavy, the rest swivel guns)

Crew (1512): 140 men (as well as 130 soldiers and 30 gunners)

Notes about the service: it was Rebuilt in 1523 and 1542 years. Participated in the battle of Portsmouth. Renamed Edward "Edward" in 1547, destroyed by fire in 1553

"Salamander" and "Swallow", 1546

Like the sister ship Unicorn, the Salamander was captured from the Scots in the Firth of forth in 1544, and later reinforced the Royal Navy of Henry VIII by joining it. By the time the ship was depicted in the Anthony Scroll two years later, all traces of oars had disappeared, although the ship still had the graceful lines of a fast oar boat. Unlike the Salamander, the Swallow Was an English-built Galleon, the type of ship that Henry VIII was fascinated with. It participated in the battle of Portsmouth, when it later became part of Elizabeth I's Navy. Overall, the ship was rated as a more efficient warship than the French-built Salamander.

Characteristics of the ship "Salamander"

Type: Galeas built in France in 1537. Captured from the Scots in 1544.

Displacement: 300 tons

The keel length of about 80 feet (24 m)

Deck width: about 22 feet (6.6 m)

Armament: 36 guns (16 heavy, the rest swivel guns)

Crew (1512): 240 men (including 130 soldiers and 30 gunners)

Changed type to a ship in 1549, and rebuilt to a Galleon in 1549. Sold in 1603.

Characteristics of the ship "Swallow"

Type: Galeas, built in 1544.

Displacement: 300 tons

Keel length: about 80 feet (24 m)

Deck width: about 22 feet (6.6 m)

Armament: 38 guns (21 heavy, the rest swivel guns)

Crew (1512): 400 men (including 180 soldiers and 20 gunners)

Declared unfit for service in 1559

Armament

In 1485, the grace Dew carried only 21 guns on Board, all hand guns resting on the side of the ship. Ten years later, in 1495, the Sovereign's inventory lists listed at least 140 guns, of which all but 31 were serpentines (hand guns). The remaining ones (20 on the waist and 11 below on the aft superstructure) were stone – throwing guns-small caliber, resembling miniminometers, capable of firing round balls carved from stone. The cannonballs flew apart on impact and were considered an excellent anti-personnel weapon – the forerunner of buckshot charges. In other words, while the grace Dew relied on archers for their firepower, the Sovereign defended itself with hand-held Riflemen reinforced with small batteries of guns firing anti-personnel cannonballs.

The Royal Navy inherited by the first Tudor monarch, Henry VII, essentially consisted of their karakk. All but one of his eight ships were of this type, with the exception of the ship named Nicholas of London-which was sold by the end of the first year of his reign. Also at this time was sold two karakki. Although we don't know much about their actual size, financial records state that all the remaining five ships were large, all former merchant ships with high fore and aft superstructures. All five carried mixed artillery from "port guns" (forged iron, breech-loading guns) and small swivel guns. These weapons of a later period were also breech-loading and usually made of forged iron, but at the same time, swivel guns were small enough to be mounted on a swivel (or rotating support) on the ship's side – a device vaguely similar to a modern machine gun.

Artistic reconstruction (Monleon, 1892)of the quarterdeck of the Columbian Santa Maria. Such primitive gun emplacements probably existed before the end of the XVI century

"Port piece" or long-barreled fogler, typical of the 2nd half of the XV-1st half of the XVI centuries, on the machine - "deck", raised from the sunken in the XVI century "Mary rose"; drawing, apparently, of the XIX century. Similar ship machines were used on ships of different countries and also had a pair of solid wooden wheels of small diameter on the axis placed under the front, "beveled" part of the machine

One of these carracks, the Mary of Tower, in 1485 carried no less than 58 guns, most of which were either portable or swivel guns. Portable guns ranged in size from small hand-held guns, to large-caliber firearms (known as arquebuses), similar to modern bazookas, and equipped with bipods that could rest against the side of the ship to reduce recoil when fired. The second ship, Grace Dieu, acquired in 1473, was listed as carrying 21 guns of the same type. Drawings such as" Warwick skating "or the Flemish print" Kraek " (as the caracca is called in Flemish) show that swivel guns could be mounted either on the waist or on superstructures, from where they could fire over the side. This arrangement of guns was possible because the guns were light enough and their weight did not affect the stability of the ship. Obviously, mounting heavy guns in the same way made the ship unstable until a way was found to mount the guns closer to the waterline. There was already a way to achieve this. The "Kraek" engraving, which dates back to about 1468, shows a large armed merchant ship with loading ports carved at the bottom of the hull, below the aft superstructure. The Warwick scroll also includes an image of a caracca sailing under the flag of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick (1428-71), armed with five or six "port" guns.

"Regent" and "Maria La Cordillera". Battle of Brest, 1512

The largest ship of the Tudor Navy before the Henry grace e'due, the four-masted Regent was a floating symbol of Tudor power, richly decorated and armed with no less than 225 guns, although almost all of them were either swivel guns or hand-held firearms. By the time Sir Thomas Nivet sailed on it and engaged the French on August 10, 1512, off Brest, the ship boasted an additional battery of heavy guns.

During the battle, the mighty ship Maria La Cordillera separated from the rest of the French fleet and was surrounded by English ships. Captain Gervais de Porzmoger, repulsed all attempts to Board his ship until, in the end, the "Regent" failed to catch on the side of the French warship. During the battle, a fire broke out on the Maria La Cordillera, and the flames quickly spread to the Regent. Soon both ships were engulfed in flames,and sank with a huge number of lives. The picture shows the moment when both ships grappled and started fighting.

Characteristics of the ship "Regent"

Type: the "Great ship" (a Carrack), originally known as the "grace Dieu". Built in 1488

Displacement: 1000 tons

Keel length: about 140 feet (42 m)

Deck width: about 45 feet ( 13.5 m)

Armament: 180 guns (mainly swivel guns and hand-held firearms)

The crew (1512): 800 people (including over 450 soldiers and 50 gunners)

Participated in the battle of Brest in 1512, and was lost in battle

The warship Sovereign, 1512

Type: "Great ship" (karakka), originally called Trinity Sovereign ("Trinity Sovereign").Built in 1488.

Displacement: 800 tons

Keel length: about 125 feet (37.5 m)

Deck width: about 40 feet (12 m)

Armament: 100 guns (most of them swivel guns and hand firearms) - 69 guns in 1509

Crew (1513): 700 men (including 400 soldiers and 40 gunners) Service notes: Rebuilt in 1509.

Participated in the naval battle of Brest in 1512.

Declared unfit for navigation in 1521 and excluded from the Navy

Warship great Bark II, 1547

Type: Galeass, originally called Great Galley "great gally". Built in 1515 in Greenwich. Sometimes known as Great Galleass "great Galleass", from 1642 it was known as Great Bark "great Bark" or Great Galleon " great Galleon"

Displacement: 800 tons

Keel length: about 100 feet (30 m)

Deck width: about 25 feet (

Armament: 87 guns (23 heavy, the rest swivel guns)

Crew (1512): 140 men (as well as 130 soldiers and 30 gunners)

Notes about the service: it was Rebuilt in 1523 and 1542 years. Participated in the battle of Portsmouth. Renamed Edward "Edward" in 1547, destroyed by fire in 1553

"Salamander" and "Swallow", 1546

Like the sister ship Unicorn, the Salamander was captured from the Scots in the Firth of forth in 1544, and later reinforced the Royal Navy of Henry VIII by joining it. By the time the ship was depicted in the Anthony Scroll two years later, all traces of oars had disappeared, although the ship still had the graceful lines of a fast oar boat. Unlike the Salamander, the Swallow Was an English-built Galleon, the type of ship that Henry VIII was fascinated with. It participated in the battle of Portsmouth, when it later became part of Elizabeth I's Navy. Overall, the ship was rated as a more efficient warship than the French-built Salamander.

Characteristics of the ship "Salamander"

Type: Galeas built in France in 1537. Captured from the Scots in 1544.

Displacement: 300 tons

The keel length of about 80 feet (24 m)

Deck width: about 22 feet (6.6 m)

Armament: 36 guns (16 heavy, the rest swivel guns)

Crew (1512): 240 men (including 130 soldiers and 30 gunners)

Changed type to a ship in 1549, and rebuilt to a Galleon in 1549. Sold in 1603.

Characteristics of the ship "Swallow"

Type: Galeas, built in 1544.

Displacement: 300 tons

Keel length: about 80 feet (24 m)

Deck width: about 22 feet (6.6 m)

Armament: 38 guns (21 heavy, the rest swivel guns)

Crew (1512): 400 men (including 180 soldiers and 20 gunners)

Declared unfit for service in 1559

Armament

In 1485, the grace Dew carried only 21 guns on Board, all hand guns resting on the side of the ship. Ten years later, in 1495, the Sovereign's inventory lists listed at least 140 guns, of which all but 31 were serpentines (hand guns). The remaining ones (20 on the waist and 11 below on the aft superstructure) were stone – throwing guns-small caliber, resembling miniminometers, capable of firing round balls carved from stone. The cannonballs flew apart on impact and were considered an excellent anti-personnel weapon – the forerunner of buckshot charges. In other words, while the grace Dew relied on archers for their firepower, the Sovereign defended itself with hand-held Riflemen reinforced with small batteries of guns firing anti-personnel cannonballs.

- Joined

- Nov 25, 2018

- Messages

- 635

- Points

- 403

By the time Henry VIII came to the throne, the composition of the fleet had changed again. In 1509, the Sovereign was armed with: 4 bronze cartouns (long-barrelled siege guns), 3 copper half-cartouns, 2 copper falcons, 7 large iron cannons, 4 copper serpentines, 42 iron serpentines (large and small), 4 iron slings ("stone throwers"), two stone-firing cannons located on the upper deck, and one culverin without a carriage. Of the 69 guns on the list, serpentines were the main hand guns, while slings were small swivel guns. Falcons were very light bronze cannons that were used only sparsely on Board the ship. Therefore, not counting the culverin without a carriage, its armament consisted of 14 heavy guns, of which just over half were muzzle-loading guns cast in bronze. Large guns (also known as port guns or "assassins") were solid forged iron guns made from iron bands bound with iron hoops, with limited range and rate of fire. However, the combination of these barrels and more modern bronze guns (cartauns and half – cartauns) meant that the Sovereign had an impressive level of firepower for its time-at a time when ships did not yet have gun ports, and if a battle began, all heavy guns were transferred to the open deck. Comparing these two inventories with later inventory descriptions of Tudor ships, it can be assumed that cartauns and half-cartauns were early prototypes of cannons and half-cannons. The armament described above was the main weapon of Henry VIII's Navy when it entered its first war with France in 1512, it was the first naval campaign of the Royal Navy where gunpowder weapons played a significant role. However, at that time, during the battle, the guns were fired once or at best twice, just before boarding the enemy ship. No one sought to use guns as a means of firing at enemy ships from a long distance – the heterogeneous composition of the artillery carried by the "Sovereign" shows that the emphasis was on short-range anti-personnel fire. And that emphasis didn't change.

to be continued...

to be continued...

- Joined

- Nov 25, 2018

- Messages

- 635

- Points

- 403

The Tudor fleet in battle

The Royal Navy of Henry VIII participated in only two full-fledged naval battles - at Brest in 1512, and in another battle - at Portsmouth in 1545. A comparison of these two battles can tell us a lot about the transformations that the Navy underwent during the reign of Henry VIII, and how warships operated in battle.

On August 10, 1512, an English fleet of 25 ships, under the command of Sir Edward Howard, attacked a French force of equal numbers, under the command of Rene de Clermont. Most of the ships on both sides were armed with swivel guns or hand guns, rather than large heavy artillery, although both the English flagship Mary rose and the French Maria La Cordillera carried 15 heavy guns each. Both fleets lined up opposite each other in a line, and then individual ships broke formation and moved forward to engage the enemy. In other words, all semblance of order quickly broke down, and the battle turned into a boarding battle between individual ships or between small groups of ships.

Howard's flagship, the Mary rose, engaged the French flagship, the Grand Louis, and a cannon salvo at close range blew her mainmast overboard. As a result, rené de Clermont retreated from the battlefield, and many others of the French captains had followed his example. Soon, only the Neuf de Dieppe and the powerful Cordillera remained surrounded by English ships. After seven hours, the smaller French warship managed to break through the encirclement of five English ships and escape. The Cordillera was not so successful. He managed to deftly maneuver two attempts to Board it by enemy ships, first by the Sovereign's crew, and then by the Mary James. Then he was challenged by the Regent, the largest warship in the Tudor Navy. The boarding party managed to throw the French off the upper deck, but then, on the verge of victory, disaster struck. A fire broke out on the French ship and within minutes the entire Cordillera was engulfed in flames. The rigging of the "Regent" and "Cordillera" became entangled with each other and the English ship could not get free. The fire inevitably spread through the sail rigging and soon both ships were engulfed in flames. Only 20 Frenchmen survived the disaster, while 120 English sailors were rescued from the fire.

This was a grim end to the incoherent battle, but the battle marked the future tactics of naval battles. First, the success of the Mary rose demonstrated the effectiveness of heavy artillery-its guns were the key to victory. It became clear that the future of naval warfare lay in the development of naval artillery and the search for better ways to use these weapons. The smaller-caliber guns also proved their usefulness – the Neuf de Dieppe managed to keep the British at Bay, using its small artillery, and thus stop all attempts at boarding. Swivel guns were highly effective in close combat, especially if there were enough spare charging chambers at hand, in order to maintain a high rate of fire. In fact, they were used as machine guns, leading a defensive barrage, to prevent attempts by boarding parties to gain a foothold on the deck of the defending ship.

Of course, other lessons were learned that are not only related to new technologies. For the most part, the English fought as they did at the battle of Sluys (1340), relying on firing fireballs and hand-to-hand combat to win the battle. Throughout the Tudor period, the Navy increased the firepower of its soldiers by training them to fight the enemy using longbows, crossbows, or hand-held firearms to thwart enemy attempts to Board the ship and then engage the enemy themselves. Illustrations from that time, as well as archaeological evidence, show that the boarding nets were attached in such a way as to serve as a protective canopy over the ship's waist – the most likely place where the ship will try to Board. Fore and aft superstructures also bristled with swivel guns and hand-held projectile-throwing weapons, these structures, which acted as bastions, largely served the same role as the defensive ramparts of fortresses. In other words, naval warfare at the beginning of the Tudor period was a strange mixture of the old and the new.

The admirals of Henry VIII, of course, tried to learn to fight in a new way. While the king focused all his efforts on improving the ships ' heavy weapons, his admirals were exploring ways to better use these new guns to gain an advantage over the enemy. To help them, in 1530, the lawyer Thomas Audley formulated a set of tactical recommendations, about halfway between the two main sea battles that took place during the reign of Henry. Despite not being a sailor, Audley did his best to solve artillery problems, and his "Instructions" seem wise for their time, although based largely on the experience of the battle of Brest.

English ships coming out of Portsmouth Harbor to engage in battle with the French.

He believed that shooting should be carried out at close range, and that boarding should be carried out only after the upper decks and superstructures of the enemy ship were cleared of the defenders with the help of artillery, swivel guns and archers. He also recommended taking advantage of the weather, in other words, taking a favorable position in the wind relative to the enemy. Audley knew that any naval battle could quickly turn into a melee in which individual ships would try to Board each other. The only suggestion that came from above that was included in his recommendations was that the pinnaces could be used to transport reinforcements from one ship to another. This was hardly an innovation – in fact, it was just a reflection of existing practice.

The opportunity to test this new doctrine came in the summer of 1545, when Tudor England faced the threat of a French invasion. A French fleet of 225 ships under the command of Admiral Claude de Annebaugh entered the Solent, the shipping route that separates the Isle of Wight from the English mainland. About a quarter of this Armada were transport ships carrying the thirty-thousand-strong French army. On 19 July, the Admiral Viscount of Lille, John Dudley, who commanded Henry's Royal fleet of about 100 ships, ordered the fleet out of Portsmouth harbour to give battle. On the morning of this day, the French Admiral sent forward a squadron of galleys, which, leaving Gosport, began a long-range bombardment of the English fleet. The British attack may have been the Viscount of Lille's response to this bombardment. Then, without warning, French observers saw the Mary rose list and sink. No doubt the French gunners thought it was their doing. In fact, the mighty Tudor warship was overloaded, and its gun ports were too close to the waterline. A sudden strong gust of wind tilted the ship, water poured into the open ports and the ship sank in a matter of minutes. English Vice-Admiral sir George Carew and 700 crew members went down with their ship.

Another painting from Cowdray house shows the battle of Portsmouth in 1545. The picture shows the moment when the ship "Mary rose" sank - the tops of her masts are still visible in the foreground of the picture, while the ship "Henry grace e'due" is still fighting with the French galleys, firing from the guns of the forward superstructure. The rest of the fleet's ships and Galleons can be seen rushing to the aid of survivors from the Mary rose.

When the French galleys stopped firing and withdrew, the English fleet returned to its anchorage. A week later, the French fleet left – the British had gathered too many forces at Portsmouth for the French to risk landing troops on the mainland, so after the RAID on the Isle of Wight, de Annebaugh went back to France, where his fleet began to help lead the siege of the British-held port of Boulogne. The battle would have added a little to our knowledge of Tudor naval operations if it hadn't been for the loss of the Mary rose. Its wreckage provided us with a snapshot of the Tudor warship of the last years of the reign of Henry VIII, and shows how far the Tudor fleet has advanced over the past three decades. Although she was still manned by archers and soldiers, and equipped with a protective net against boarding, the Mary rose had a powerful onboard artillery armament.

Although the design of the Mary rose probably made it difficult for her to participate in active naval battles with the use of artillery, due to the cramped conditions on Board, she was a formidable opponent, able to capture an enemy ship, after a devastating broadside made at point-blank range, and a fierce assault on the enemy ship, after its defenders were nullified by cannon fire and archery. Thus, she was a bright representative of the transition period in the war at sea. It was designed to fight in boarding battles, but it also had weapons that could deal damage to the enemy from afar, using only firepower. However, it was only after the death of Henry VIII that the Tudor Royal Navy began to prioritize the use of naval artillery over hand-to-hand combat. This tactic was implemented by the sailors who served Henry's daughter Elizabeth, who were able to fully apply all the new technologies, and under Elizabeth, the Tudor Navy finally became the most powerful naval force of its era.

The Royal Navy of Henry VIII participated in only two full-fledged naval battles - at Brest in 1512, and in another battle - at Portsmouth in 1545. A comparison of these two battles can tell us a lot about the transformations that the Navy underwent during the reign of Henry VIII, and how warships operated in battle.

On August 10, 1512, an English fleet of 25 ships, under the command of Sir Edward Howard, attacked a French force of equal numbers, under the command of Rene de Clermont. Most of the ships on both sides were armed with swivel guns or hand guns, rather than large heavy artillery, although both the English flagship Mary rose and the French Maria La Cordillera carried 15 heavy guns each. Both fleets lined up opposite each other in a line, and then individual ships broke formation and moved forward to engage the enemy. In other words, all semblance of order quickly broke down, and the battle turned into a boarding battle between individual ships or between small groups of ships.

Howard's flagship, the Mary rose, engaged the French flagship, the Grand Louis, and a cannon salvo at close range blew her mainmast overboard. As a result, rené de Clermont retreated from the battlefield, and many others of the French captains had followed his example. Soon, only the Neuf de Dieppe and the powerful Cordillera remained surrounded by English ships. After seven hours, the smaller French warship managed to break through the encirclement of five English ships and escape. The Cordillera was not so successful. He managed to deftly maneuver two attempts to Board it by enemy ships, first by the Sovereign's crew, and then by the Mary James. Then he was challenged by the Regent, the largest warship in the Tudor Navy. The boarding party managed to throw the French off the upper deck, but then, on the verge of victory, disaster struck. A fire broke out on the French ship and within minutes the entire Cordillera was engulfed in flames. The rigging of the "Regent" and "Cordillera" became entangled with each other and the English ship could not get free. The fire inevitably spread through the sail rigging and soon both ships were engulfed in flames. Only 20 Frenchmen survived the disaster, while 120 English sailors were rescued from the fire.

This was a grim end to the incoherent battle, but the battle marked the future tactics of naval battles. First, the success of the Mary rose demonstrated the effectiveness of heavy artillery-its guns were the key to victory. It became clear that the future of naval warfare lay in the development of naval artillery and the search for better ways to use these weapons. The smaller-caliber guns also proved their usefulness – the Neuf de Dieppe managed to keep the British at Bay, using its small artillery, and thus stop all attempts at boarding. Swivel guns were highly effective in close combat, especially if there were enough spare charging chambers at hand, in order to maintain a high rate of fire. In fact, they were used as machine guns, leading a defensive barrage, to prevent attempts by boarding parties to gain a foothold on the deck of the defending ship.

Of course, other lessons were learned that are not only related to new technologies. For the most part, the English fought as they did at the battle of Sluys (1340), relying on firing fireballs and hand-to-hand combat to win the battle. Throughout the Tudor period, the Navy increased the firepower of its soldiers by training them to fight the enemy using longbows, crossbows, or hand-held firearms to thwart enemy attempts to Board the ship and then engage the enemy themselves. Illustrations from that time, as well as archaeological evidence, show that the boarding nets were attached in such a way as to serve as a protective canopy over the ship's waist – the most likely place where the ship will try to Board. Fore and aft superstructures also bristled with swivel guns and hand-held projectile-throwing weapons, these structures, which acted as bastions, largely served the same role as the defensive ramparts of fortresses. In other words, naval warfare at the beginning of the Tudor period was a strange mixture of the old and the new.

The admirals of Henry VIII, of course, tried to learn to fight in a new way. While the king focused all his efforts on improving the ships ' heavy weapons, his admirals were exploring ways to better use these new guns to gain an advantage over the enemy. To help them, in 1530, the lawyer Thomas Audley formulated a set of tactical recommendations, about halfway between the two main sea battles that took place during the reign of Henry. Despite not being a sailor, Audley did his best to solve artillery problems, and his "Instructions" seem wise for their time, although based largely on the experience of the battle of Brest.

English ships coming out of Portsmouth Harbor to engage in battle with the French.

He believed that shooting should be carried out at close range, and that boarding should be carried out only after the upper decks and superstructures of the enemy ship were cleared of the defenders with the help of artillery, swivel guns and archers. He also recommended taking advantage of the weather, in other words, taking a favorable position in the wind relative to the enemy. Audley knew that any naval battle could quickly turn into a melee in which individual ships would try to Board each other. The only suggestion that came from above that was included in his recommendations was that the pinnaces could be used to transport reinforcements from one ship to another. This was hardly an innovation – in fact, it was just a reflection of existing practice.

The opportunity to test this new doctrine came in the summer of 1545, when Tudor England faced the threat of a French invasion. A French fleet of 225 ships under the command of Admiral Claude de Annebaugh entered the Solent, the shipping route that separates the Isle of Wight from the English mainland. About a quarter of this Armada were transport ships carrying the thirty-thousand-strong French army. On 19 July, the Admiral Viscount of Lille, John Dudley, who commanded Henry's Royal fleet of about 100 ships, ordered the fleet out of Portsmouth harbour to give battle. On the morning of this day, the French Admiral sent forward a squadron of galleys, which, leaving Gosport, began a long-range bombardment of the English fleet. The British attack may have been the Viscount of Lille's response to this bombardment. Then, without warning, French observers saw the Mary rose list and sink. No doubt the French gunners thought it was their doing. In fact, the mighty Tudor warship was overloaded, and its gun ports were too close to the waterline. A sudden strong gust of wind tilted the ship, water poured into the open ports and the ship sank in a matter of minutes. English Vice-Admiral sir George Carew and 700 crew members went down with their ship.

Another painting from Cowdray house shows the battle of Portsmouth in 1545. The picture shows the moment when the ship "Mary rose" sank - the tops of her masts are still visible in the foreground of the picture, while the ship "Henry grace e'due" is still fighting with the French galleys, firing from the guns of the forward superstructure. The rest of the fleet's ships and Galleons can be seen rushing to the aid of survivors from the Mary rose.

When the French galleys stopped firing and withdrew, the English fleet returned to its anchorage. A week later, the French fleet left – the British had gathered too many forces at Portsmouth for the French to risk landing troops on the mainland, so after the RAID on the Isle of Wight, de Annebaugh went back to France, where his fleet began to help lead the siege of the British-held port of Boulogne. The battle would have added a little to our knowledge of Tudor naval operations if it hadn't been for the loss of the Mary rose. Its wreckage provided us with a snapshot of the Tudor warship of the last years of the reign of Henry VIII, and shows how far the Tudor fleet has advanced over the past three decades. Although she was still manned by archers and soldiers, and equipped with a protective net against boarding, the Mary rose had a powerful onboard artillery armament.

Although the design of the Mary rose probably made it difficult for her to participate in active naval battles with the use of artillery, due to the cramped conditions on Board, she was a formidable opponent, able to capture an enemy ship, after a devastating broadside made at point-blank range, and a fierce assault on the enemy ship, after its defenders were nullified by cannon fire and archery. Thus, she was a bright representative of the transition period in the war at sea. It was designed to fight in boarding battles, but it also had weapons that could deal damage to the enemy from afar, using only firepower. However, it was only after the death of Henry VIII that the Tudor Royal Navy began to prioritize the use of naval artillery over hand-to-hand combat. This tactic was implemented by the sailors who served Henry's daughter Elizabeth, who were able to fully apply all the new technologies, and under Elizabeth, the Tudor Navy finally became the most powerful naval force of its era.

- Joined

- Nov 25, 2018

- Messages

- 635

- Points

- 403

This drawing is based on a well-known engraving kept in the Palace of Cowdray house, depicting the French attack on Portsmouth on July 19, 1545. In the original, a squadron of four French galleys bombards the English fleet as they approach it to engage in battle. These galleys fired a broadside and moved back to reload their guns, a tactic similar to the Caracol maneuver used by the pistol-armed cavalry of that era. Deviations in our drawing from the engraving are associated with the ships Mattew Gonson "Matthew Gonson" and "Mary rose". In the original, only the tops of the masts of the Mary rose are visible on the surface of the water, while boats pick up a small handful of survivors.

Our drawing shows the moment when the ship "Mary rose" began to sink, the water rushed inside the ship through the ports of the gun deck. Sir Gawain Carew, who was on Board the Matthew Gonson, was close enough to hear his uncle on Board the Mary rose when sir George Carew reportedly shouted that "I can't control this rabble." So we took the nephew's ship a little further back to the background. The Henry grace e'due can be seen firing her bow guns at the French galleys.

Over the centuries, the site of the famous shipwreck, lying near the coast, was found several times and lost again. Finally, in 1966, the remains of the ship were once again discovered, examined and clearly mapped. The survey showed that part of the starboard hull structures, part of the ship's guns and a significant number of various small household items from that period survived. Marine archaeologists have made sure that the preserved oak parts of the hull can withstand the ascent to the surface without the risk of destruction. In 1979 the Board of Trustees of the ship was created to make comprehensive preparations for lifting the ship from the bottom of the Solent Strait. In 1982, this training was successfully completed and the lifting operation went almost without a hitch. Currently, this unique monument to the history of shipbuilding can be seen in the Museum created specifically for it in Portsmouth. Next to other famous monuments of the history of shipbuilding – the battleship "victory" and the sailing-screw ship "warrior".But this is a slightly different story.

Fin

Our drawing shows the moment when the ship "Mary rose" began to sink, the water rushed inside the ship through the ports of the gun deck. Sir Gawain Carew, who was on Board the Matthew Gonson, was close enough to hear his uncle on Board the Mary rose when sir George Carew reportedly shouted that "I can't control this rabble." So we took the nephew's ship a little further back to the background. The Henry grace e'due can be seen firing her bow guns at the French galleys.

Over the centuries, the site of the famous shipwreck, lying near the coast, was found several times and lost again. Finally, in 1966, the remains of the ship were once again discovered, examined and clearly mapped. The survey showed that part of the starboard hull structures, part of the ship's guns and a significant number of various small household items from that period survived. Marine archaeologists have made sure that the preserved oak parts of the hull can withstand the ascent to the surface without the risk of destruction. In 1979 the Board of Trustees of the ship was created to make comprehensive preparations for lifting the ship from the bottom of the Solent Strait. In 1982, this training was successfully completed and the lifting operation went almost without a hitch. Currently, this unique monument to the history of shipbuilding can be seen in the Museum created specifically for it in Portsmouth. Next to other famous monuments of the history of shipbuilding – the battleship "victory" and the sailing-screw ship "warrior".But this is a slightly different story.

Fin

An interesting log. Takes be back a few months; I started it in May.

Some interesting changes from my Caldercraft kit.

It looks as though your lime planks are actually 600mm long as it states in the parts list. Mine were only 500mm

and I stumped up £17 to Cornwall Model boats for some longer ones. Your deck timbers seem to be a different colour:

mine were whitish tanganyika - I don't know which are more authentic.

I have almost completed the hull: haven't done the hatches yet. I see you have done a lot of deck work early.

I've diverted to doing some rigging (spars, shrouds etc.) so I don't have to do it all at once.

Some interesting changes from my Caldercraft kit.

It looks as though your lime planks are actually 600mm long as it states in the parts list. Mine were only 500mm

and I stumped up £17 to Cornwall Model boats for some longer ones. Your deck timbers seem to be a different colour:

mine were whitish tanganyika - I don't know which are more authentic.

I have almost completed the hull: haven't done the hatches yet. I see you have done a lot of deck work early.

I've diverted to doing some rigging (spars, shrouds etc.) so I don't have to do it all at once.

- Joined

- Nov 25, 2018

- Messages

- 635

- Points

- 403

There is no excuse for his writings.Translation through transliteration.The source is here https://pikabu.ru/story/voennyie_korabli_yepokhi_tyudorov_5113424 it's really written in Russian.The pictures are also there.I wrote through my phone, without pictures.

I’m finding it difficult to get information on gun emplacements and type for Mary Rose. I realise there was a mix but, placement and type seems pretty important

Does anyone have information please.

My build begins tomorrow

I guess the best information you can find in this book (which I do not have unfortunately)

Weapons of Warre: the armaments of the Mary Rose

Edited by Alexzandra Hildred

here is a review:

also interesting and maybe helpful

The Mary Rose – Part 2

Written about 5 years ago, and a lot of differences to how I’d do it now, but still a useful overview, I think. The Mary Rose- A Unique 16th Century Resource for Reenact…

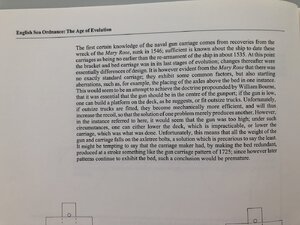

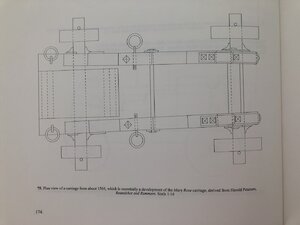

and these excerpts about the Mary Rose armament are from the book "The History of english Sea Ordnance - Volume I - The Age of Evolution 1523-1715" by Adrian B. Caruana published by Jean Boudriot Publications in 1994

Hope these information are of some help

- Joined

- Jul 7, 2020

- Messages

- 82

- Points

- 113

Why would you hijack this mans build log of MARY ROSE, I really don’t understand why you would cut and paste not even your own words, interesting though it’s. WHY?Type: the "Great ship" (a Carrack), nicknamed "great Harry". Built in 1514 at Woolwich

Displacement: 1000 tons

Keel length: about 130 feet (39 m)

Deck width: about 50 feet (15 m)

Armament: 80 guns (51 heavy, the rest swivel guns; in the inventory list of weapons on Board a total of 112 guns, including hand firearms

Crew (1536): 700 men (including 400 soldiers and 40 gunners)

One of the most ambitious warships built during the Tudor dynasty, its construction is probably a direct response to the construction of the ship Great Michael ("great Michael") by the king of Scotland – James IV. Unfortunately, it took three decades before the ship was able to open fire with its guns, most of the time it spent on conservation. The ship was built more for prestige than for any military value, and in 1520 she accompanied Henry VIII from Dover to Calais to meet Francis I on the " Field of Golden brocade»:

Even then, the ship's displacement prevented it from leaving or entering the Harbor. While its appearance was impressive, the cost of operating it in peacetime was considered prohibitive, and it came to be regarded as a kind of "white elephant". The drawing shows one of the forged iron breech-loading guns that the ship was armed with, mounted on a carriage.

Another notable feature of the 15th-century North European karakka was the shape of its stern. The hull skin (or belt of the ship's outer skin) curved at the top of the stern, forming a more rounded stern of the ship than on ships of later construction. This feature can be seen on the Hulk of the time. From 1488 and later, this practice ceased to simplify the construction of the ship, when the skin belt was attached to the aft frames of the ship, and a transom (flat) stern was added. This simplification became important when it was necessary to build heavy ships capable of withstanding heavy artillery fire.

to be continued...

Why would you hijack this mans build log of MARY ROSE, I really don’t understand why you would cut and paste not even your own words, interesting though it’s. WHY?

Well, he could have started a new thread for sure but it looks like Graham doesn't mind. And the information is valuable even if it is not MD's own making. He took the effort to translate and type it in!

János

- Joined

- Nov 25, 2018

- Messages

- 635

- Points

- 403

You asked for any information.I just didn't cut the pieces out of the article.I hope the whole article gave people some knowledge.If it is interesting on the link provided by me, the person conducted the study of historical materials himself.Its Mary Rose model is clearly different from that given by Caldercraft.Why would you hijack this mans build log of MARY ROSE, I really don’t understand why you would cut and paste not even your own words, interesting though it’s. WHY?

Hi. You mentioned the deck colour - for this I used an oil stain, medium teak.An interesting log. Takes be back a few months; I started it in May.

Some interesting changes from my Caldercraft kit.

It looks as though your lime planks are actually 600mm long as it states in the parts list. Mine were only 500mm

and I stumped up £17 to Cornwall Model boats for some longer ones. Your deck timbers seem to be a different colour:

mine were whitish tanganyika - I don't know which are more authentic.

I have almost completed the hull: haven't done the hatches yet. I see you have done a lot of deck work early.

I've diverted to doing some rigging (spars, shrouds etc.) so I don't have to do it all at once.

Hi. If you are building the Caldercraft kit then the gun types and placements are shown on the plan sheets, or are you scratch building?I’m finding it difficult to get information on gun emplacements and type for Mary Rose. I realise there was a mix but, placement and type seems pretty important

Does anyone have information please.

My build begins tomorrow

Back in the shipyard after quite a long break and I hope you and yours are keeping well in these difficult times.

Next job is to complete the additional forward castle deck. Same techniques as I posted earlier for the additional rear castle deck....

While things are drying I can get on with the internal framing on the bulwarks and there is quite a bit of that to do with 1.5mm x 1.5mm strip. This is the rear castle deck finished -

Next job is to complete the additional forward castle deck. Same techniques as I posted earlier for the additional rear castle deck....

While things are drying I can get on with the internal framing on the bulwarks and there is quite a bit of that to do with 1.5mm x 1.5mm strip. This is the rear castle deck finished -